|

|

From 1930 to 1950, a rebirth of the medieval and Renaissance technique of tempera painting took place in America. Prominent artists from New York City to Pennsylvania’s Brandywine River Valley, including the influential Wyeth family artistic dynasty, embraced the revitalized technique.

|

|

|

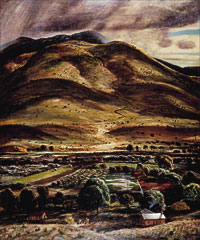

Peter Hurd (1904–1984), The Rainy Season, 1947, pure egg tempera on gesso on masonite, 48 x 40 inches. Collection of the Roswell Museum and Art Center; courtesy of the Brandywine River Museum. In Milk and Eggs: The American Revival of Tempera Painting, 1930–1950.

|

The history of tempera painting predates oil painting to the twelfth century. At its height of popularity, egg tempera (in which egg yolk is used to bind pigments) was the primary medium used by fourteenth-century Italian painters. However, after the sixteenth century, pigments ground in oil became more widely used, and tempera was relatively discarded for nearly 400 years.

Tempera once again regained popularity during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A series of American revivals occurred in architecture, painting, and sculpture as interest in classical, Gothic, and Renaissance art increased. As artists studied works of the past, they also became interested in the use of historical methods of painting.The Yale University School of Fine Arts was one of the first centers of the revival. In the late 1920s, Daniel V. Thompson, Jr., taught a studio course in tempera and published on the subject. His successor, Lewis York, continued the course through 1950, teaching artists such as Saul Levine (b. 1915).

At the Art Students’ League in New York City, mural painting courses taught by Kenneth Hayes Miller (1876–1952) and Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) in the 1930s promoted tempera as the ideal medium for large works. Benton went on to influence artists working in the Regionalist style through his teaching at the Kansas City Art Institute.

|

|

|

|

Andrew Wyeth (b. 1917), Raccoon, 1958, tempera on panel, 48 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the Brandywine River Museum. In Milk and Eggs: The American Revival of Tempera Painting, 1930–1950.

|

In Chadds Ford, nestled in Pennsylvania’s Brandywine River Valley, Peter Hurd (1904–1984) took to the medium in the 1930s and shared it with his teacher, N.C. Wyeth (1882–1945), and other students, including Wyeth’s son, Andrew (b. 1917). Egg tempera became Andrew’s primary medium, which he employed in his most acclaimed works, such as Christina’s World. He continues to use it to this day.

The Brandywine River Museum examines tempera’s twentieth-century reemergence in Milk and Eggs: The American Revival of Tempera Painting, 1930–1950, which includes more than fifty works by artists such as Andrew Wyeth, Thomas Hart Benton, Jackson Pollack, John Sloan, and Paul Cadmus. The exhibition is on view at the Brandywine River Museum, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, now through May 19, 2002. A 230-page catalogue is available. Info: www.brandywinemuseum.org; tel. 610.388.2700. It travels to the Akron Museum of Art (OH), June 15 to September 1, 2002, and then to the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, September 21 to November 17, 2002.

|

On the Market

|

|

|

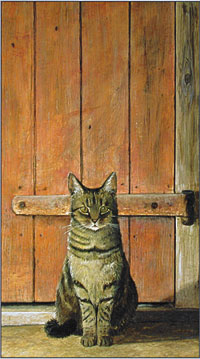

Karl J. Kuerner (b. 1957), Doorstop, acrylic, 23 x 211/2 inches. Courtesy of David David Gallery, Philadelphia..

|

From the medium’s rebirth in the 1930s to today, a tradition of tempera painting has been maintained by two generations of Wyeths: N.C. and Andrew. The family has seasonally resided in Chadds Ford for almost 100 years. Ensconced in their familiar country, Andrew and his son Jamie (b. 1946) continue to paint the seemingly ordinary land and people in an extraordinary way—their work conveys something beyond the surface that relates to popular imagination. “Life is strange,” Andrew once commented in a rare interview, “from the outside, things may look one way, but when you look inside, they’re very different.”

The family patriarch, and perhaps the most renowned American painter/illustrator of the early twentieth century, N.C. Wyeth used tempera mostly for large-scale commissioned public murals, which can be seen in banks and institutions. Today, Andrew’s major temperas can sell for several million dollars. Jamie, who is represented by James Graham & Son in New York, prefers oil and mixed media. “My father works in tempera,” Jamie once commented, “which I did try. All the properties he likes I dislike and vice versa.”

Andrew’s wife, Betsy, helped establish the Brandywine River Museum and Conservancy in Chadds Ford. She also contributed to organizing the opening exhibition Wondrous Strange in 1997 at the inauguration of the Wyeth Center at the Farnsworth Museum in Rockland, Maine, near the family’s summer homes and studios.

|

Another major Wyeth exhibition was the National Gallery of Art’s sensational 1987 blockbuster of “the Helga pictures.” The show revealed seventeen years’ worth of nude portraits of Chadds Ford neighbor Helga Testorf, painted by Andrew mostly in fast-drying tempera. Helga was a German immigrant hired as a caretaker at the Kuerner Farm, one-third mile down the road from the Wyeths.

In addition to Helga, the Kuerner Farm provided Andrew with the rural subject matter of farmers, a barn and animals, hills, and valleys for nearly 1,000 works painted over several decades. As a boy, Karl J. Kuerner, Jr. (b. 1957) watched Andrew paint and went on to become an artist himself. Kuerner’s works of the people and places he loves are created mostly with acrylic and watercolor, with a result akin to Andrew’s temperas.

Kuerner helped preserve his historic family farm by both donating and selling the land and buildings to the Brandywine Conservancy; the farm may be open for tours in the future. Nearby, N.C. Wyeth’s studio is open for tours through the Brandywine River Museum. Info: tel. 610.388.2700.

|

Tempera

The word tempera derives from the medieval Latin temperare, meaning “blending or mixing.” Today, the word indicates a medium bound with emulsions, combined with dry pigments and water. Techniques employ either egg yolks (egg tempera) or milk proteins (casein tempera) as principal emulsions.

The physical and visual properties of tempera are what entice artists. For some, the attraction lies in the “old school” discipline of mixing the paint, preparing the surface, and applying the tempera in layers. Tempera also dries quickly, and once dry it becomes insoluble, allowing the artist to paint over without disturbing underlying layers. The appearance of a matte finish as opposed to the glossy quality of oil paint also draws followers. Finally, tempera’s durability, proven by the fact that so many fifteenth-century works are remarkably preserved and fresh-looking today, is also an alluring factor to artists.

|

|

|