|

|

To become proficient in the evaluation of antique furniture, the student must understand the basic concepts of construction, methodology, and design. When learning about American eighteenth-century furniture, in particular, the most elemental identifying characteristics—often relating to regionalism or construction techniques—are usually the first committed to memory: that the seat frames of Philadelphia chairs were made with exposed rear tenons, that cabriole legs were made from a single piece of stock, and that block fronts were carved from one piece of wood, for example. The tendency is to rely on basic principles when looking at furniture, yet there are many variants; for example, rear tenons are not always visible on Philadelphia chairs, cabriole legs were occasionally made of several pieces of stock to achieve the necessary width, and some blocking was applied rather than carved from solid drawer fronts. Just as a good diagnostician in medicine looks beyond the medical journals, a student of antiques recognizes that this is not an exact science and that there are as many exceptions as there are rules.

|

|

Highboy, Newbury, Massachuestts, 1749

This masterpiece in curly maple is unmistakably an original unit, evidenced in part by the consistency of the striping in the wood, which is indicative of boards cut from the same tree, and by the retention of the original engraved cotter pin brasses that have never been out of their original holes. The name Elizabeth Noyes is painted in script on the back boards (left).

Just as with the Salem highboy noted in the text, the construction features of the upper and lower case sections demonstrate the work of different hands: The shape of the dovetails as well as the thickness of the drawer linings vary. To support the evidence of the highboy’s manufacture as a unit, however—besides the consistency of the wood and brasses—are the surviving signatures of the craftsmen. Cabinetmaker Joshua Morss signed his name and dated the lower section “January 1748/9”1 (left); his partner, Moses Bayley, inscribed the upper section with his name and “Newbury, February AD 1748/9” (above). This time frame corresponds with the January marriage of 18-year-old Elizabeth Noyes (1731–1817) to Captain James Smith (1725–1787); the highboy was apparently commissioned from the Newbury cabinetmakers as a dowry for Noyes.2

Generally, craftsmen were responsible for making specific components in a shop environment, such as the drawers or frame—hence explaining similarity in construction of most upper and lower case sections. The evidence presented with this example, however, reinforces that there are no hard and fast rules: Morss and Bayley, rather than dividing skill-oriented tasks, divided the work between the upper and lower sections. In my experience, I have seen half a dozen examples of varying techniques on a genuine highboy, which just happen to be the exception. This does not negate the need for corroborative evidence of compatibility among components when variations are found.

Inset lower left: Back of lower case drawer signed “Made by/Joshua Morss/Jan 1748/9.”

Inset lower right: Upper case section signed “Made by Moses Bayley Newbury/February AD 1748/9”

|

|

|

|

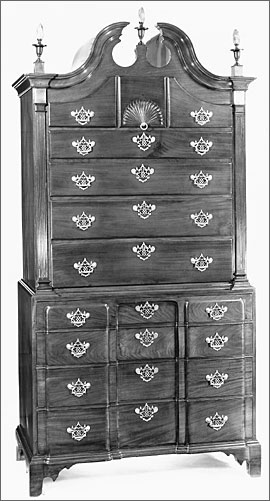

Chest on chest, Massachusetts, circa 1770

Another variation seen occasionally is in the finishing of drawer surrounds on New England chests on chests. In the example shown here, the drawers of the lower section are flush with the beaded edges of the dividers. The drawers of the upper case instead have overlapping, quarter-round lip borders. When the chest was built, either a decision was made to create visual differences in design or it was an oversight of execution.

|

One of the main lessons people learn early on is that while marriage is a hallowed institution in society, it means buyer beware when relating to antiques. The tops and bases of many high chests, for example, have been separated over the generations—the top going to Aunt Millie to serve as a chest of drawers, the base to Uncle Harry for use as a dressing table. At times, two compatible upper and lower sections are joined to form a complete unit, an unholy marriage. How does one tell if this has happened? First and foremost one is taught to compare the drawer dovetails and construction of the upper and lower sections—if they are not the same, then the object is married.

This test is fine as a general rule, but should not be carved in stone. In my early days as an antiques dealer, I saw a number of obvious marriages. My first encounter with a questionable union, however, was probably thirty or more years ago when my friend Phil Budrose, of Marblehead, took me to see a Salem bonnet-top highboy. One of the finest examples I have ever seen, it featured matching carved fans on both the top and bottom, the original double pine-tree-pattern brasses with shoe strings to substitute for missing bails, a cruddy, untouched surface, and a very attractive offering price. The problem centered on the fact that the structure of the upper and lower case sections—dovetails, drawer linings, and runners—were entirely different. Even with these variations, I had a sense that the piece was originally made as a unit, and I was ready to buy it. Yet as a good organization man, I called my brother Harold and explained the situation as well as my conviction. My buddy Lester Berry, whose father was an old-time dealer in Connecticut, was with me at the time. He got on the phone with Harold and said, “My father taught me that if the dovetails don’t line up top to bottom, it’s a marriage.” I then asked Harold, “You trust my judgment, don’t you?” He replied, “Of course I do, but I am getting too old for controversy.” I didn’t buy that masterpiece, and it is now in a private collection that we visit occasionally—I still covet that highboy.

|

|

|

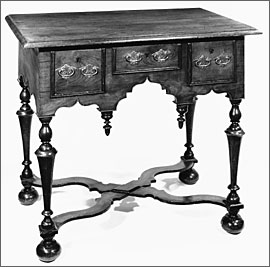

Lowboy, Pennsylvania, circa 1720

This William and Mary lowboy descended through the family of its original Pennsylvania owners. When we examined it for possible purchase, we noticed that the legs were made in two sections. Students are taught that William and Mary legs are turned in one piece, and if found otherwise, the legs have been replaced. Yet we could see that the elements retained the same original, untouched surface, and that undisturbed rosehead nails held the legs in place. We concluded that the legs were originally made in two parts and bought the lowboy. Afterward, the lowboy, along with ten to twelve related examples, was x-rayed for research purposes. Six others displayed the same construction in which the bulbous shapes above the trumpet turnings were separate elements—thus a newly identified technique was added to the history books.3

|

The examples illustrated on these pages reinforce the point that when evaluating antiques, it is necessary to have an open mind. Don’t make hasty judgments based purely on standard criteria, but assess other factors and corroborating evidence. While it is always important to be critical, it is also necessary to take into account that craftsmen worked with the tools and materials they had at hand, having to compensate for many different circumstances. When asked how I react to variations in furniture, I say that finding something I have never seen before is one of the most exciting things about the field.

All photography courtesy of Israel Sack, Inc.

Albert Sack is a principal of Israel Sack, Inc., New York, New York.

|

- The date 1748/9 is the old system used for designating the first three months of the new calendar year.

- For more information on Moses Bayley (1716–1778) and Joshua Morss (1714–1756), cabinetmakers on High Road in Newbury, see Peter Benes, Old Town and The Waterside (Historical Society of Old Newbury, 1986), pp. 30–31.

- The research on this construction technique was conducted by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. For reference information see Jack Lindsey, Worldly Goods (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999), p. 144, fig. 50.

|

|

|