|

|

|

|

|

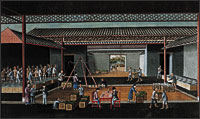

| Unknown artist, A Tea Hong at Canton, ca. 1800–1825. Tea is being packed and sealed in crates, then weighed and prepared for loading onto a junk. In the center foreground, merchants negotiate the shipment. Courtesy of Tudor Place, Washington, D.C. This gouache is part of the exhibition Asian Arts at Tudor Place: An American Passion to Collect, on view April 30 to December 31, 2002, at Tudor Place in Washington, D.C. The neoclassical Tudor Place was built in 1816 by Thomas Peter and his wife, Martha Custis Peter, a granddaughter of Martha Washington; it was home to six subsequent generations. Now a National Historic Landmark, Tudor Place is exhibiting for the first time an extensive collection of Chinese export and Asian artifacts collected by the Peter and Washington families over nearly two centuries. |

“Pray let them be neat and fashionable or send none,” wrote 26-year-old George Washington to an English trader in 1758. The future general and president was writing of his desire for Chinese export porcelain, an important status symbol for eighteenth-century gentry. He and Martha were among any number of American and European upper- and merchant-class patrons in search of the most modish porcelain—the strong, hard-paste type whose manufacturing process was for many years a Chinese secret.

Since Roman times, a small amount of exotic goods from the East had trickled down the slow and dangerous cross-country “Silk Road.” The sixteenth-century discovery of a sea route to China began a mad rush among the European superpowers to control the trade. Besides spices and silk, a major motivation was tea: Westerners clamored for the leafy export as well as its porcelain accoutrements that the Chinese made best.

“Billions of pieces” of Chinese export porcelain made their way to western markets, estimates Villanova, Pennsylvania, collector and dealer Elinor Gordon. Yet only a limited amount survives today: Some of it sank, was broken in transport, or has been damaged over time.

|

|

|

|

An extremely rare China-trade soapstone (steatite) carving of Peter the Great in armor, probably dating from his reign, 1687–1725. The gold-piqué point insets are unusual in Chinese carvings and suggest manufacture in the imperial workshops. H: 81/2". Copyright 2002 by the Kelton Foundation. The Kelton Foundation owns an extensive collection of China trade art and objects; works from the collection are on loan to museums such as the Smithsonian, The Getty, and San Diego Art Museum.

|

This coveted cargo often passed through Canton, situated on the tidal Pearl River. “The most interesting city in China…with respect to wealth and size,” Canton was also described as a “frontier town” by early nineteenth-century observers. During the height of the export era—between about 1720 and 1860—Canton (now called Guangzhou) was the only city that let westerners set up shop in the form of factories or “hongs,” for mercantile activities. By the late eighteenth century, there were about thirteen hongs (the number fluctuated with fires and building additions) that were associated with the major trading nationalities—the Dutch, Swedes, Spaniards, French, Americans, and British. Ensconced on a quarter-mile of land near the city walls, each nation’s hong was distinguished by its flag flying high above the Pearl. Here, “foreign devils,” as the traders were known to the Chinese, conducted business, but were forbidden to bring their wives, enter the city gates, or ride in sedan chairs.

Trading headquarters and residencies for the western merchants consisted of river-facing buildings connected by gardens and courtyards. Each hong contained a number of specialized spaces such as counting rooms, storage, sleeping quarters, banquet rooms, and a treasury.

“In front of the factories was the spot, the Square with Jackass Point,” wrote an eighteenth-century eyewitness. A landing for ships coming up from Whampoa and a point of departure for river excursions, the square was a “resort for fresh air and gossip” for westerners. After the Great Fire of 1822, Chinese peddlers took to the square to sell local delicacies such as pickled olives. Sometimes, the place would become so congested with traders and peddlers that the police were called in to clear it. Life on the river was ceaseless too, thick with western ships and a floating population of Chinese in junks and other vessels.

The picturesqueness of the port was not lost on visitors. At the same time, there were darker realities. Around dusk, boats laden with opium worth tens of thousands of dollars (England’s export to China) scrambled for cover. Occasionally, a vessel carrying wares from Whampoa would try to sneak past the Canton inspection station, Hoppo House; the result was sometimes violence.

|

|

|

|

| Chinese-export porcelain plate with grisaille views of London and Canton, ca. 1735. Courtesy of the U.S. Dept. of State, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, Washington, D.C. To the traders of the British East India Company, the scene at Canton’s harbor was in many ways similar to the bustling Thames in London; both were inland river ports. This plate is from a service made for Eldred Lancelot Lee (English, 1650–1734), a relative of General Robert E. Lee. |

Trading in Canton was a gamble for westerners. Round-trip sea journeys, planned around the monsoon season, lasted two years and were fraught with difficulties. At sea, pirates, storms, rival merchants, and disease posed constant risks to the venture. In port, there were taxes, bribes, and deceptions. But the possibility of huge rewards spurred on traders.

After the Revolution, enterprising American shipping merchants built fortunes in the China trade. America’s first millionaire, Elias Hasket Derby, initiated Salem into the trade; he followed the outfits of Robert Morris, a Philadelphia gentleman who had bankrolled the Continental army.

In 1784, Morris’s The Empress of China was the earliest American ship to reach Canton, returning with luxury perishables and porcelain to replace the commonly used (and now known to be poisonous) pewter ware. By the early 1800s a young United States was the biggest market for export porcelain (England was making its own wares and taxed Chinese export at over 100 percent), yet American traders were unaffectionately nicknamed “second-chop Englishmen” by the Chinese merchants.

|

|

|

|

Attributed to Youqua (Chinese, active 1840–1870), View of Canton, ca. 1850. This view of the port gives a sense of the width of the Pearl River and the density of its traffic. Among the various Chinese and western rigs are two American sidewheelers. Photo courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques, Hyannisport, MA., and Northeast Auctions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Collectors today recognize that Canton ware, distinguished by its “rain and cloud” border and freely painted blue-and-white scene, works well in almost every interior and with most collections: Asian, European, or American; formal or country; fine or folk art. Photo courtesy of a private collection.

|

Mass-produced export porcelain was, however, of little consequence to the profitability of a China trade voyage.1 Stored in the ship’s leaky hold as ballast, some of the less expensive porcelain was used as a support for precious silk and tea cargos. In 1810, an auction in Boston disposed of the contents of the American ship Pearl. The net profit was an excellent $206,650.47: Made up of porcelains worth 2.4 percent, teas worth 14.1 percent, and silks worth 83.5 percent of the total.

|

|

|

Hong punch bowl with a continuous view of Canton, ca. 1785. Courtesy of the U.S. Dept. of State, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, Washington, D.C. As the fashion for punch declined after 1800, paintings of similar port views replaced hong bowls as souvenirs of the China trade. This superb bowl was sold by dealer Elinor Gordon to the Dietrich American Foundation, who in turn sold it to the Fine Arts Committee of the U.S. State Dept.

|

The China trade suffered a series of blows in the nineteenth century resulting in its steady decline. Catastrophic fires, native uprisings, the 1840s opium wars, and an increased availability of European porcelains added to the misfortunes of the various trading companies.

Remarkably, for nearly four centuries the art and objects of the China trade have remained popular. “At the time of its manufacture, the decoration on Chinese export seemed otherworldly and very exotic to Americans and Europeans. Today, those same objects are familiar and classic to people all over—besides representing an enormously exciting period in history,” explains a Virginia collector.

|

|

|

|

|

Silver mug with Canton scene, ca. 1840. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA. Photography by Mark Sexton.

|

On the Market

Views of Canton depicted on porcelain and lacquerware, and in ivory, jade, silver, or oils, bear witness to the magnificent port in its heyday as the heart of the China trade. Representations of the port itself can be found on so-called hong bowls, a variety of decorative objects, and in paintings by Chinese and western artists both unknown and identified, such as the English painter George Chinnery (1774–1852).

With paintings, American collectors look for scenes displaying American flags flying from ships or above the hongs. Alan Granby, a dealer in Hyannisport, Massachusetts, also points out that the number of western ships, yachts, or crew races that appear in a painting adds considerably to its value. Many collectors are drawn to works done in the 1850s when ship architecture was considered to be at its height; others prefer earlier scenes. Generally, a detailed Canton scene in good condition brings in the range of $60,000 to $125,000. A large painting depicting several western ships, perhaps retaining its original Chinese export frame, might fetch upwards of $250,000.

|

|

|

|

Chinese artist, Waterfront Buildings at Honam, late 1850s. Oil on canvas, 12 x 17 inches. Courtesy of Martyn Gregory, London. After the destruction of the hongs by fire in December of 1856, the western merchants lodged on the opposite bank of the Pearl, on the island of Honam, until a new concession was developed a little upstream at Shamian Island. In this unusual view, the foreign merchants’ accommodations are viewed at close quarters, with a westerner depicted on the verandah to the right and two others being rowed ashore.

|

Hong bowls, decorated with lively polychrome hong scenes, are avidly sought by modern collectors. Elinor Gordon recalls selling an especially good one with the combined powerhouse elements: displaying an American flag, in perfect condition, and having a provenance in one family since 1745. Proving their desirability, very fine hong bowls command $50,000 to $100,000.

One prolifically produced ware is now commonly referred to as Canton.2 With its freely painted pattern of willow trees, pagoda, bridge, and boat, it was used as everyday china in late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America and, less so, in Europe. Relatively affordable, accessible, and its classic blue and white palette having a wide appeal, the characteristics of Canton are as desirable today as two centuries ago.

|

|

|

|

Youqua (Chinese, active 1840–1870), A Panoramic View of the Waterfront at Canton, ca. 1845. Oil on canvas, 33 1/2 x 78 inches. Attached to the canvas is a fragment of Youqua’s label with his studio address of 34 Old Street, Canton. Courtesy of Martyn Gregory, London.

This remarkably wide panorama encompasses the entire river frontage from the western suburbs on the left to the French folly fort at the extreme right. The Dutch folly fort, with its thicket of banyan trees, appears in the center right, and beyond it is the old city of Canton backed by White Cloud Mountain. Visible on the skyline are the three landmarks of Huai Sheng Mosque, built in the Tang dynasty as a lighthouse; the Flowery Pagoda; and the Zenhai Tower.

The series of western hongs, rebuilt after the fire of 1841, are depicted in the center left. The numerous Chinese craft cruising the Pearl River range from seagoing and inshore junks to sampans and Tanka boats. The dark green “flower boats” held female flower sellers, seen here through the latticework portals.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This pair of garden barrels, ca. 1810–1820, constitute “the best Canton I’ve ever offered,” says dealer John Suval. Courtesy of Philip Suval, Inc., Fredericksburg, VA.

|

The market for Canton keeps escalating, according to dealer Julie Lindberg of Wayne, Pennsylvania. “Canton went up one-third in value last year and has doubled over the past ten years.” A Massachusetts collector notes, “These days there’s more competition for the rarer pieces.” The shaped forms that collectors readily seek include coffee and tea pots (approx. $1,500 retail) and cider jugs (approx. $3,000 retail). Graduated sets of pitchers and covered boxes are also very popular for their “display aesthetic.” Recently, five covered boxes brought $19,500 at auction.

|

|

|

|

At Left: Chinese export oval dish with scene of Dutch folly fort on the Pearl River near Canton, ca. 1780. Courtesy of Paul Vandekar, Earle D. Vandekar of Knightsbridge, Inc., New York. At Right: Mother-of-pearl and hand-painted paper Chinese export fan, ca. 1850. The obverse side includes three watercolors of Chinese ports: Canton, Macau, and Hong Kong. The reverse shows colorful flowers, peacocks, butterflies, and a grasshopper. Courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques, Hyannisport, MA.

|

|

|

Age, condition, color, rarity of form, and quality of decoration factor into Canton’s price. Lindberg looks for pieces with fully developed medium-blue decoration and for subtle features such as gracefully-scooped sides on a cut-corner bowl as opposed to flat edges. Decorations on plates, she says, appear “sloppy” because they were purportedly painted by children. Collectors can garner dinner plates for about $200 each. Matched candlesticks are also a good find, according to Lake Forest, Illinois, dealer Matthew Lunn.

|

|

|

|

Selection of rare Canton porcelain: A lidded water bottle, 20-inch platter, cider jug with lid and foo-dog finial, pair of matching ewers, three-piece soap dish, 6-inch square covered box, and censor teapot, ca. 1800–1850. Courtesy of Julie Lindberg, Wayne, PA.

|

|

|

Canton ware has experienced a reversal of fortune since clipper ships laden with it swept into ports such as Salem and Liverpool. In 1810, the Pearl’s cargo contained 50 blue-and-white dinner sets consisting of 172 pieces each, which netted $2,290. Today, that amount might buy a single Canton lidded cider jug with a foo dog finial.

|

|

For period quotes used in this article see: James Orange, The Chater Collection (London, 1924) 191, 205–213.

|

|

Suggested Reading

|

|

|

|

Artist unknown, Western Hongs at Canton, ca. 1812. Courtesy of Quester Gallery, Stonington, CT.

From left to right range the Danish, Spanish, American, Swedish, British, and Dutch flags flying above their respective headquarters. To the left of the American hong is the entrance to Old China Street flanked by a guardhouse with lanterns; this street of shops serviced western merchants. To the left of the British hong is the salacious Hog Lane, an eight-foot alley that was the resort of sailors on leave from Whampoa.

The Canton hongs shown here were completely destroyed by fire in 1822. They were later rebuilt only to be consumed by fire in 1841 and again in 1856. After 1856, the hongs were never rebuilt and the area today is a park containing every sort of entertainment from fairground rides to opera. |

Conner, Patrick. George Chinnery 1776–1852: Artist of India and the China Coast. Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1993.

Crossman, Carl L. The Decorative Arts of the China Trade. Woodbridge, Suffolk, England: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1991.

Detweiler, Susan. George Washington’s Chinaware. New York: Harry Abrams, 1982.

Schiffer, Herbert, Peter, and Nancy. Chinese Export Porcelain, Standard Patterns and Forms, 1780 to 1880. Exton, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1975.

Keay, John. The Honourable Company: A History of the English East India Company. London: Macmillan, 1991.

Mudge, Jean. Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade, 1785–1835. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1962.

Wilson, Jane. Canton for the Collector. Essex, CT: Riverside Press, 1977.

|

|

- While far removed from the imperial ware of China, porcelain that was made for export is attractive to collectors today for its distinct, historical character. Named for varying polychrome palettes and stylized decorations were several fine export wares such as famille verte, famille rose, rose mandarin, rose medallion, FitzHugh, and Nanking. Special orders made through agents of the trading companies included services with heraldic or fraternal order decorations.

- Assembly-line manufacture involved scores of Chinese workers in the production and decoration of objects. A single cider pitcher would be handled by numerous individuals, each assigned a specific task, such as painting a pagoda.

|

|

|