|

|

|

Works from the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection

and Insurance Company Collection at the Florence Griswold Museum

|

|

by Hildegard Cummings

|

|

Although native and foreign-born artists had been working as portraitists in New England since about 1670, Connecticut hosted no professional artist until William Johnston (1732–1772) came to New London in 1762. By then, middle-class families had gained importance in virtually every town in the state and had the interest and means to order portraits. In contrast to the elegant English style favored by the aristocratic families, the middle class were often depicted in a primitive manner by artists with little or no formal training. Early Connecticut folk portraiture, characterized by capable observation and bold design elements, satisfied a patronage seeking images that portrayed them as strong individuals who had achieved eminence not by birth, but by character and work.

After the Revolution, the leading artist in Connecticut was Ralph Earl (1751–1801), a Massachusetts native who was active in several towns, painting more than 100 portraits in the late 1780s and early 1790s. To give his patrons the look of virtue, good character, and industry that they continued to demand, Earl tempered the refined style he had learned from American expatriate Benjamin West (1738–1820) while they sat out the American Revolution in England.

|

|

|

|

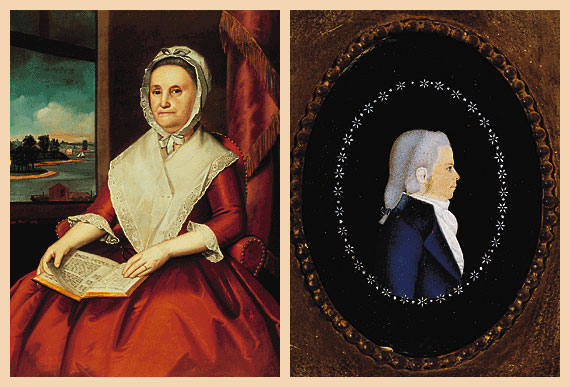

Fig. 1 (at left): Ralph Earl (1751–1801), Mrs. Guy Richards of New London, 1793. Oil on canvas, 43 x 32 3/4 inches. Mrs. Richards’ grandson is depicted by Mary Way in Fig. 2. Fig. 2 (at right): Mary Way (1769–1833), Portrait of Peter Richards. Watercolor and collage on silk, 2 3/4 x 2 1/2 inches.

|

|

|

|

On his arrival in Connecticut, Earl was among people who believed that modesty, piety, and republicanism were primary. His 1793 portrait of Elizabeth Harris Richards depicts the sitter holding Family Espositor: or, A Paraphrase and Version of the New Testament, a popular guide for family worship by Philip Doddridge (1702–1751), the English Calvinist (Fig. 1). Counterbalancing the reference to religious devotion is a reminder of the family’s financial success. The window view behind the sitter shows her husband’s New London wharf and his successful dry goods business.

Earl’s mix of primitive and sophisticated elements inspired several local followers who have become known as the Connecticut school. Among them are Ammi Phillips and the lesser-known Mary Way and Harlan Page.

|

Mary Way (1769–1833) has the distinction of being one of the earliest professional women artists in America. In 1790s New London, she specialized in miniature watercolor portraits on paper or silk, which she usually “dressed” with cloth or, in the instance of Peter Richards’ portrait (Fig. 2), glued on paper. Richards (b. 1778) was a son of Guy Richards, Jr., the city treasurer. Way also painted his brother, and probably everyone else he knew, for she eventually ran out of clients in her hometown. In 1811, at age 42, Way moved to New York City. When she went blind from glaucoma in 1820, John Trumbull (1756–1843) and Samuel Waldo (1783–1861), leading New York artists and fellow Connecticut natives, organized a benefit exhibition for their “sister of the brush.” The proceeds settled her bills and gave her something to live on back in New London.

|

|

|

|

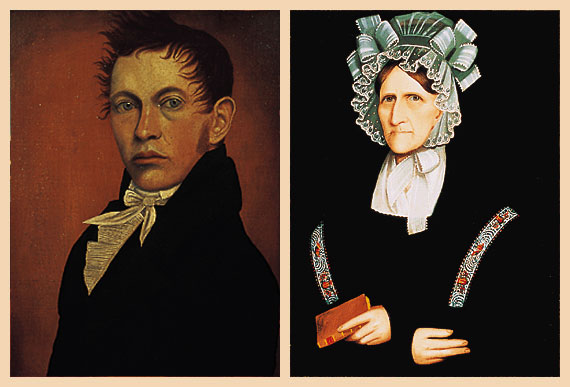

Fig. 3 (at left): Harlan Page (1791–1834), Portrait of a Man, ca. 1815. Oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 18 3/4 inches. Fig. 4 (at right): Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), Portrait of Katherine Salisbury Newkirk Hickok, ca. 1825. Oil on canvas, 32 x 27 inches.

|

|

|

Only two portraits have been identified as by the hand of Harlan Page (1791–1834). This Coventry, Connecticut, schoolteacher worked tirelessly to convert everyone he came into contact with to Christianity. The portrait shown here (Fig. 3), perhaps a self-portrait, is thought to be a representation of an individual experiencing the Second Great Awakening, the nineteenth-century religious revival that set Page’s soul on fire. “A glow of heavenly ardor burned in our brother’s countenance,” wrote his biographer.

Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), a native of Colebrook, Connecticut, is now considered one of America’s premier nineteenth-century folk painters. However, for several decades after his death his identity was unknown. Phillips, like many folk artists, did not sign many of his works. For years he was referred to as the Kent Limner or Border Limner, for the regions he worked in that encompassed northwestern Connecticut and into Massachusetts and New York. The discovery of a signed portrait in 1958 revealed his identity and led to the attribution of about 500 paintings. The portrait shown here probably dates from the early 1820s, when Phillips was modeling faces with an uncompromising realism (Fig. 4). His work of this period was also characterized by his sitters’ dark clothes and backgrounds highlighted with a few striking decorations, such as the fancy gauze bonnet that so smartly sets off Mrs. Hickok’s sharp features and earnest gaze.

|

Artists in Connecticut made significant and distinctive contributions that have an enduring charm. Their portraits convey the personalities and document the social history of the state centuries ago.

|

|

|

Hildegard Cummings is consulting curator of The American Artist in Connecticut at the Florence Griswold Museum and co-author with museum director Jeffrey Anderson of the accompanying exhibition catalogue.

All illustrations from the gifted collection of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company to the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut.

|

|

|

|

Antiques and Fine Art is the leading site for antique collectors, designers, and enthusiasts of art and antiques. Featuring outstanding inventory for sale from top antiques & art dealers, educational articles on fine and decorative arts, and a calendar listing upcoming antiques shows and fairs.

|