|

| Home | Articles | Curator's Choice: Henry Pratt's Account for Lemon Hill |

|

|

by Martha Halpern

|

|

|

|

|

Rear elevation of Lemon Hill. This view illustrates the curved projecting bay formed by the series of oval rooms, one stacked above the other, on each of the three floors. Photography courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art.

|

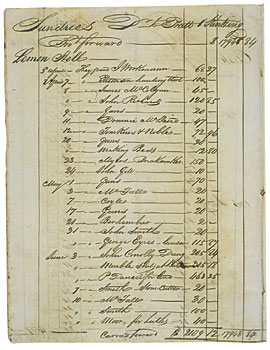

In 1962 a tin rainwater conductor head bearing the date 1800 was found in the attic of Lemon Hill. Thought to indicate the year of the construction of Henry Pratt’s (1761–1838) country seat, the date can now be substantiated through the discovery of a written account at the William L. Clements Library of the University of Michigan,1 in Ann Arbor. The account, which documents for the first time not only the date of Lemon Hill’s construction but also the craftsmen who built it, is included in the vast collection of original source materials and papers belonging to Pratt and his business partner, Abraham Kintzing.2 Pratt’s account contains a record of his personal expenses for the years 1800–1801, which covers the construction of Lemon Hill. Unfortunately, records have yet to surface that document the interiors and original furnishings. Nonetheless, from Pratt’s account, curators can now gather valuable data regarding the house’s construction and garner insight into Pratt’s decorative taste from his furnishing purchases for a town house on North Front Street in Philadelphia.

|

|

|

|

Lemon Hill account. First of six pages. 1800–1801. Pratt & Kintzing, Business Papers. Courtesy of William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.

|

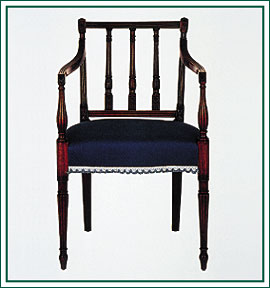

In 1798, according to his account, Pratt ordered a silver sugar dish from his business representative in London. He also asked his London agent for fine satin to be made into drapes for “Mrs. P.” He left the choice of colors and pattern to his agent. They were to be “the best and most elegant & not Plain,” but not “very showy or tawdry.” In the spring of 1800, he paid a sea captain, whose ships were known to have traded at Canton, for “Tea China &c.” He also paid John King, merchant, “for Andirons &c.” In May, Pratt purchased furniture at “Liston’s vendue,” a local sale of the furniture of Robert Liston, the British minister to the States. The advertisement for this sale indicates that some of this furniture “was very elegant.” In June, Pratt paid Ephraim Haines, cabinetmaker, for “dining Tables.” It is likely that these purchases were intended for Pratt’s house on North Front Street. At this time, construction on Lemon Hill was in its early stages and not yet ready for furnishing.

The newly discovered account indicates that Pratt began work on his country house in April 1800, when he ordered lumber from a local merchant. He then paid for the services of a “stonecutter,” plasterers, a “tinman,” a glazer, and a turner to make balusters, such as those on the side porches of the house. In February 1801, Pratt purchased a quantity of luxurious mahogany that was most likely used for the doors of the first-floor oval room; each section is cut from a solid piece that conforms to the curve of the walls.

|

|

|

|

Armchair attributed to E. Haines, ca. 1800–1810. Mahogany. H. 34 1/2 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1986 26-58; on loan to Lemon Hill; photography courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art.

|

Pratt’s account clearly documents that he was acting as his own contractor, buying the materials and hiring each individual craftsman and laborer, most of whom are listed in Philadelphia city directories. While the role of the trained professional architect was just beginning to evolve, most houses and buildings during this period were designed and built by the talented amateur. It was common practice for a gentleman, working with a builder or master carpenter and using design books and examples of other buildings, to design and build at least his own country seat, and Pratt was working in this tradition. It is unclear, however, where Pratt got his inspiration for the unusual design and plan of Lemon Hill. The house is unique in Philadelphia for the period because of its series of three oval rooms, one stacked above the other, with double-hung windows to maximize the river view. While Pratt’s account provides no reference to a design source, there is some precedent in America for this type of architectural feature: Charles Bulfinch’s Joseph Barrell house (1792–1793) in Somerville, Massachusetts, and James Hoban’s White House, built in 1792 in Washington, D.C., are early examples of the elliptical or oval room in American architecture. Likewise, The Woodlands (ca. 1780s), nearby, features a sophisticated elliptical dining room and parlor. However, such high-style neoclassical rooms in America in 1800 were rare. The newly-discovered account shows that Pratt was responsible for Lemon Hill’s extraordinary, and at the time cutting-edge, Franco-Adamesque Federal design, which was compatible with his preference for similarly elegant, high style English and American furnishings.

|

Martha Crary Halpern is Assistant Curator for Fairmount Park Houses, Department of American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

|

Selected Bibliography:

|

For an account of the renovation of Pratt’s town house, see his neighbor’s diary: Elaine Forman Crane, ed., The Diary of Elizabeth Drinker, Vol. II, July 20, 1798, to May 4, 1799 (Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 1991).

For insight into Pratt’s taste in furnishings, see Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia: Library Company of Philadelphia, April and May 1800). Also, “Henry Connelly and Ephraim Haines,” The Philadelphia Museum Bulletin XLVIII (Spring 1953), 42–43. And Charles F. Montgomery, American Furniture of the Federal Period (Winterthur, DE: The Viking Press, 1966).

Harold Kirker, The Architecture of Charles Bulfinch (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969), 45–53.

Virginia N. Naude, “Lemon Hill Revisited,” The Magazine Antiques (April 1966): 578–579.

|

|

Notes:

|

- Pratt’s account was purchased by library director John C. Dann from an Ohio dealer in 1979. It was part of a large collection of papers owned by an Ohio family that related to Philadelphia merchants.

- The author found the account while researching the Fairmount Park houses. They were loosely organized, but not catalogued.

|

|

|