|

| Home | Articles | Thomas P. Moses: Artist, Musician & Poet of Portsmouth, New Hampshire |

|

|

by Richard M. Candee

|

Thomas Palmer Moses has long been recognized as a marine artist and folk painter, yet the facts about his life have often been confused. Most writers have misidentified his birth and death years (1808–1881) as well as his working dates (1855–1875). The Groce and Wallace Dictionary of American Artists mistook his uncle for his father, both also named Thomas Moses, thus turning nephew Samuel C. Moses (1818–after 1850), a mid-nineteenth-century religious enthusiast and miniaturist, into T. P. Moses’s son. An odd mistake, given that Moses remained unmarried until the age of 68. This confusion is not entirely surprising, for even in his day, Moses recognized the need to differentiate himself from his father and uncle by using his middle initial. Some of these misconceptions were corrected by scholar John LaBranche in Sotheby’s auction catalogue for the 1994 Nina Fletcher Little sale of Moses’s last and best painting, the Charles Carroll, which also illustrates the cover of Nina Little’s 1984 book Little by Little (Fig. 1).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Ship Charles Carroll. Signed on reverse, On the Piscataqua from north end of Noble’s Bridge/Original. Thos. P. Moses/Portsmouth, N.H./The Fall of 1875. Oil on canvas, 41 1/2 x 54 inches. Collection of William Gilmore; photography courtesy of Portsmouth Athenæum.

|

In 1942 Jean Lipman, the early promoter of American folk arts, listed Moses as a painter of ships working about 1850. Yet all but one of his dated paintings were executed between 1866 and 1875. In fact, what has not been clear until now is how little painting Moses actually did; he earned his living into his 40s as a musician and poet.

The life of cultural entrepreneur Thomas P. Moses (Fig. 2) offers a revealing case study of nineteenth-century artistic self-invention. Moses was born into a poor Portsmouth area family and as a youth was apprenticed as a house servant. Moses availed himself of opportunities, however, and while attending a local school, he became one of its teaching assistants, continuing as a teacher throughout his life. Moses learned to play music and by the 1840s was the city’s leading church organist, choir director, and private music instructor. During this period local newspapers regularly published his poetry, both with his own name and under pseudonyms. His writing explored nature, temperance, music, love, and other sentiments and was compiled into the book Leisure Thoughts in Prose & Verse (1849). If not for a personal row with the leaders of the church where he was organist and choir master from 1843 to 18491, it is entirely possible that Moses might never have turned his hand to painting.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Portrait of Thomas P. Moses, from Leisure Thoughts in Prose & Verse (Portsmouth, 1849). Courtesy of Portsmouth Public Library.

|

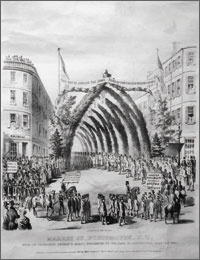

Dismissed from his positions in 1849, Moses continued to give private music lessons and manage concerts. His financial circumstances, however, were strained, and thus in 1852 he advertised his availability to “give lessons in sketching from nature, and in Crayon Drawing on Marble board.”2 While there are newspaper descriptions of his “colored crayon” or sandpaper pastels from the early 1850s, none has been found. His best-known product of this period is a Bufford lithograph (Fig. 3) published by Moses and a local photographer and marketed to returning native sons as far away as New York and Philadelphia.

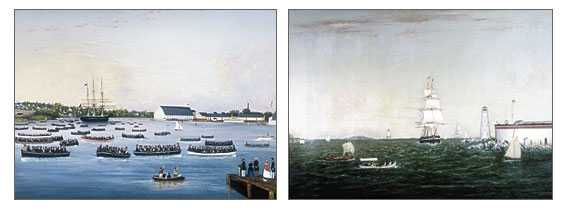

Apparently, little extra income was generated from these ventures, for in 1854 he relocated to Brooklyn, New York, and one year later to Boston, Massachusetts, to study art. Despite earlier claims of his being a marine artist during the 1850s, the Entrance Portsmouth, N.H. Harbour (Fig. 4), signed and dated on the back of the canvas with Boston, Dec. 1855, is Moses’s first known oil painting. The harbor is seen with Fort Point at New Castle, New Hampshire, on the lower right and Whaleback lighthouse in the upper left. One of two ships in the center flies a Dutch flag. The other is the Hope Goodwin, launched in Portsmouth in 1851, but burned by a mutinous crew in 1854. Perhaps the painting was a memorial for her owner and longtime Moses patron, Ichabod Goodwin. It seems likely that this painting was done under a teacher’s guidance, as Moses’s handling is more precise and refined than the somewhat naive versions of the same view he would later paint.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Market Street, Portsmouth N.H. with the Triumphal Arches and Grand Procession of the Return of the Sons July 4, 1853. Lithograph by J.H. Bufford, Boston, published by Albert Gregory and Thos. P. Moses. 11 x 14 inches. Courtesy of Portsmouth Athenæum; photography courtesy of the author.

|

Still in search of a steady income, Moses sailed to Charleston in 1856, settling in upland South Carolina where he tutored children in music. He was trapped there during the Civil War and left for Portsmouth late in 1866. While in the South, he kept a now-missing sketchbook, which he used on his return to paint Autumn in South Carolina. Originally Sketched on the spot by Thos. P. Moses/ Portsmouth, N.H./Sept. ‘67 (Fig. 5).3 This image depicts the rural character of western South Carolina where Moses lived and demonstrates his range of painting beyond the maritime scenes for which he became most recognized.

On his return, Moses found a different environment than ten years before. As noted in his obituary, “A new generation had arisen, and younger men had taken the place he once had occupied”4 as a musician, and he found that the taste for his romantic poetry had begun to wane. Without a musical position, he focused his attention on his art and began to paint commercially, selling several hundred dollars’ worth in the first few months of 1867. So popular were these “Gems of Art” that Moses had “to close his door to enable him to keep pace with the buyers.”5

|

Many of Moses’s early paintings were derived from imaginary or print sources. With the advent of lithography and photography, art was more accessible to a new audience, and like many artists of his day, Moses expanded his repertoire by copying these new readily accessible images. The images Moses copied are often apparent by the titles, which either were the same as the source or expanded slightly for clarification. As noted in the New-Hampshire Gazette, the Portsmouth public responded, “his fancy and copied paintings find[ing] ready sale.”6 Among the print sources copied was The Haunted Stream (Fig. 6) after an 1846 painting by the Irish émigré artist James Hamilton. The print was one of two that Moses copied from The American Gallery of Art (1848). Why Moses was copying images produced twenty years prior is uncertain; other print sources he followed were more contemporary.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Entrance Portsmouth, N.H. Harbour by Thos. P. Moses Boston, Dec. 1855. Oil on canvas, 28 11/16 x 33 11/16 inches in frame. Courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum; photography courtesy of Peter E. Randall.

|

Moses also painted local scenes (Fig. 7), often designated as “Original” in the long titles he gave them. He never signed his paintings on the front, but rather titled, signed, and often dated them on the back of the canvas. While some were sold to the area’s tourist industry, many of his paintings remained in Portsmouth. The Portsmouth Journal noted in August 1870, “His skill has repeatedly been shown in some very superior scenes which now adorn the parlors of our most wealthy citizens.”

The most common subject chosen by Moses was the Piscataqua River, on which the town of Portsmouth is situated. As his 1881 obituary noted, “No one ever loved a home more ardently than did Mr. Moses his native city…. Especially did he delight in the river, and never wearied of extolling its beauties.” Among the most interesting of his river scenes is Coming from the Navy Yard Portsmouth, signed Thos. P. Moses/Aug. ‘67 (Fig. 8). Some of the 1,500 workers on board dozens of long boats at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard across the Piscataqua are shown on their way home from work. This rush hour scene was so popular that the September 7, 1867, Portsmouth Journal noted:

|

Fifty applications have been made for the picture, but the author being a great lover of his native home scenes retains it for the present for its peculiar associations. He intends, however, to issue a large and splendid fac-simile Lithographic Engraving of this picture, when subscriptions will warrant the expense.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Autumn in South Carolina. Original Sketched on the spot by Thos. P. Moses Portsmouth, N.H., Sept. ‘67. Oil on canvas, 27 1/8 x 20 1/4 inches. Courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum; photography courtesy of Peter E. Randall.

|

Unfortunately, at $2.50 apiece, not enough buyers subscribed for him to make a lithograph of the painting. This result is not unexpected, for despite claims of great financial success after recasting himself as an artist, Moses seems to have struggled to sell his paintings, frequently offering them in large batches for lotteries or as door prizes at his musical concerts to garner enthusiasm and recognition for his work.

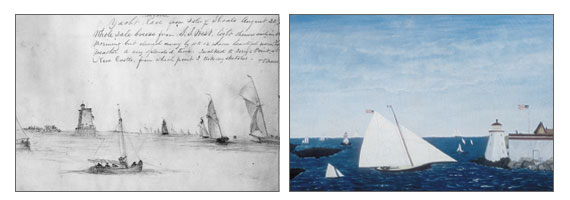

Sick during the winter of 1871–1872, the next spring Moses advertised that he was done with painting, divesting his remaining works primarily through lottery. Yet by 1874, he returned to the easel with several variations of his old study of Portsmouth Harbor, including two historical views, one of which is illustrated in Figure 9. In August 20, 1874, Moses noted in his sketchbook that he “walked to Jerry’s Point at New Castle, from which point [he] took [his] sketches” (Fig. 10). By September he had turned the sketches into one or more paintings, and in June 1875 someone won through lottery an 18 x 27-inch oil called The Yacht Race (Isles of Shoals) valued at $20. Perhaps this was the folk art painting of the harbor with a sailboat (Fig. 11), which probably lost its title when it was relined. It looks very like another by this Portsmouth artist, rather than an English-born Thomas Moses (1856–1934) to whom the Philadelphia Museum of Art has long misattributed its nearly identical signed Moses painting of Portsmouth Harbor.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: The Haunted Stream, Thos. P. Moses, Portsmouth, NH, 1871. Oil on canvas, 24 1/4 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Strawbery Banke Museum; photography courtesy of Peter E. Randall.

|

Moses never seemed wedded to any one particular style of painting—his works ranged from naive to painterly. Since most of Moses’s works were painted for sale through lottery, the variations most likely do not relate to client requests but may be a result of available time, or more likely, his personality, which through his poetry, music, and art had many forms of expression.

The last known Thomas P. Moses painting was his masterpiece (see Fig. 1). On the verge of again leaving Portsmouth for the South to teach, Moses painted the harbor with a view from the bridge to Noble’s Island looking across the Piscataqua, painted the greenish blue he favored, to Badger’s Island and the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, with St. John’s Episcopal Church towering over the Ceres and Bow Street wharves on the right. The central feature, the schooner Charles Carroll under a Captain Cudworth out of Rock-land, Maine, was a regular visitor to Portsmouth. The old Gloucester-built ship kept a regular run between the city and her home port in the early 1870s.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Marston’s Island in Portsmouth Harbor from the Cemetery East on Great Pond, Evening View at High Water by Thos. P. Moses the fall of 1870. Oil on canvas, 22 x 30 inches. Private collection; photography courtesy of Peter E. Randall.

|

The Portsmouth Journal called this work “the finest specimen of art ever executed in Portsmouth.” Like many of Moses’s earlier works, this and a lost companion landscape with cattle were “disposed of for the benefit of the artist, in shares or otherwise.”7 This 1876 lottery helped send him and his new bride8 to South Carolina, where Moses taught art to children at Marietta Academy near Greenville. No later paintings by him are known. He returned to Portsmouth for the last time, sick and alone9, just months before his death in 1881.

Thomas Palmer Moses’s obituary noted, “His versatile genius turned its attention of late years to painting, in which department of art he was to a good degree successful.”10 Yet, Moses was soon forgotten, his paintings relegated to attics or cellars. During the last century, only a handful of his paintings have been exhibited or sold to a burgeoning market for marine paintings and American folk art. Yet, there is more known about Moses’s life—due to his music, poetry, paintings, and numerous newspaper accounts—than many other nineteenth-century American artists. His many accomplishments not only provide a glimpse into the life of perhaps a typical struggling entrepreneur, but also document Portsmouth at the nadir of its maritime economy.

|

|

|

Fig. 8 (left): Coming from the Navy Yard, Portsmouth, signed T.P. Moses/Aug. ‘67. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches. Private collection; photography courtesy of Peter E. Randall. Fig. 9 (right): Entrance to Portsmouth Harbour in the Glory of Her Commerce (ca. 1830), signed and dated April 1874. Oil on canvas, 36 x 26 1/4 inches. Private collection; photography courtesy of Peter E. Randall.

|

|

Of some 200 works that may have been painted by Moses from late 1866 to 1875, less than two dozen are accounted for. Except for a few now lost or unavailable, these remaining paintings form the exhibit The Artful Life of Thomas P. Moses from February 14 through June 15, 2002, at the Portsmouth Athenæum, open Tuesday and Thursday 1–4 p.m. and Saturdays 10 a.m.–4 p.m.

|

|

|

Fig. 10 (left): A pencil sketch of the “Yacht races from the Isle of Shoals,” signed and dated Thos. P. Moses, August 20, 1874. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum. Fig. 11 (right): The Yacht Race, attributed to T.P. Moses. Oil on canvas, 18 x 26 inches. Private collection; photography courtesy of Peter E. Randall.

|

|

Richard M. Candee is professor of American and New England Studies at Boston University. A past president of the Portsmouth Athenaeum, he is guest curator and author of the exhibition catalogue The Artful Life of Thomas P. Moses (2002).

|

|

Notes:

|

- Moses detailed the events of the feud in his book A Sketch of the Life of Thomas P. Moses…by himself (Portsmouth, 1850).

- “Musical Notice,” Portsmouth Journal (October 23, 1852), p.3.

- Only two images from his time in the South are known from documents: an unlocated Charleston sketch titled “Alonzo and Zimena” and a landscape painting for which he won a prize at the Edgefield District Fair.

- “Thomas P. Moses,” New Hampshire Gazette (November 24, 1881), p.6.

- “Communication,” Portsmouth Morning Chronicle (March 15, 1867), p.3.

- New-Hampshire Gazette (May 25, 1867), p.2.

- Portsmouth Journal (January 1, 1876), p.2.

- Moses married Ellen M. Franklin (1842–1920), of Portsmouth, in a “very sudden” Boston wedding.

- When Moses is listed as a border in South Carolina, no mention is made of his wife. She returned north by 1880 and resided in Jamaica Plain, MA, until her death in 1920.

- “Around Home,” Portsmouth Journal (November 29, 1881), p.3.

|

|

|

|