|

|

|

|

|

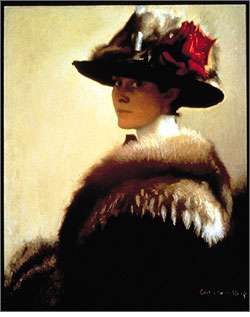

Fig. 1: Ellen Day Hale (American, 1855–1940), Self-Portrait, 1885. Oil on canvas, 28 1/2 x 39 inches. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of Nancy Hale Bowers. 1986.645

|

In 1889, a writer for the journal The Art Amateur declared, “There is nothing that men do that is not done by women now in Boston.”1 The city nurtured the talents of women in many fields, including literature, education, medicine, and particularly the arts. Boston became especially well known for its dynamic sisterhood of women painters, sculptors, designers, and photographers. Their creative community is the subject of A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870–1940 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Boston has a long history of supporting women artists, but in the decades after the Civil War, when women’s roles began to shift significantly within American society, their numbers greatly increased. In the 1860s, painters William Rimmer (1816–1879) and William Morris Hunt (1824–1879) offered classes especially for women, believing, as Rimmer remarked in a letter of 1864, that art is “as independent of sex as thought itself.”2 Both men gave their women students thorough training in drawing, including rendering the human figure, a course of study that was fundamental to a traditional art curriculum. The dissent such instruction caused in the art world is difficult to comprehend today, but drawing from a live nude model, particularly a male subject, was a serious transgression of appropriate ladylike behavior. Both parents and the popular press equated such activity with the loss of maidenly innocence, and women who sought to become serious artists had to accustom themselves to controversy.

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Lilian Westcott Hale (American, 1880–1963), Portrait of Nancy (The Cherry Hat), ca. 1914. Charcoal, 28 1/2 x 21 1/2 inches. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of Nancy Hale Bowers. 1986.646

|

The numerous articles in popular journals by women about their experiences as art students seem united in one thing—their descriptions of life-drawing classes as hard work that required concentrated effort, an activity that left no room for titillating thoughts or deeds. “There is no sex here,” wrote A. Rhodes in The Galaxy in 1873, “the students, men and women, are simply painters.”3

The dedication and determination of these aspiring women artists is reflected in Ellen Day Hale’s (1855–1940) authoritative self-portrait (Fig. 1). The daughter of the Unitarian minister and writer Edward Everett Hale and his wife, Emily Perkins, Hale had shown an early interest in drawing. She studied anatomy with Rimmer and painting with Hunt. In the company of one of Hunt’s most devoted students, Helen Knowlton (1832–1918), Hale traveled around Europe in 1881. She then settled in Paris, enrolling at the Académie Julian, which was committed to anatomy and figure painting. Hale learned her lessons well, and her self-portrait, the last work she completed in Paris, marks the high level of her achievement. When the painting was exhibited in Boston, the reviewer for The Art Amateur in January 1887 described it as “refreshingly unconventional” and admitted that Hale’s work “displays a man’s strength.”4 Renouncing typical representations of demure lady artists, Hale instead created an image of great force and power.

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Gretchen Rogers (American, 1881–1967), Woman in a Fur Hat, ca. 1915. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 1/4 inches. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; gift of Miss Anne Winslow. 1972.232

|

Hale contributed to Boston’s art world both through her own work and through hersupport of a younger generation of aspiring artists. Among the women who benefited from her pioneering efforts was her sister-in-law, Lilian Westcott Hale (1880–1963). Lilian’s letters to Ellen are full of details about art, and Ellen acted as her confidante and champion. Lilian came to Boston in 1900 to enroll at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, one of the new schools of art that had been founded in the city during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. After her first year of study, Lilian was formally introduced to Philip Hale (1865–1931), an instructor of drawing at the Museum School and Ellen’s brother. They soon fell in love, and Lilian was forced to reconcile her ambition to be an artist with the reality of marriage. Opinions differed on the matter—the painter Anna Lea Merritt (1844–1930) had cautioned women in the March 1900 issue of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine that “women who work must harden their hearts, and not be at the beck and call of affections or duties or trivial domestic cares,” adding that “the chief obstacle to a woman’s success is that she can never have a wife.”5

Lilian proved that it was possible to balance a career and a family. She earned a reputation as a talented professional, successfully exhibiting and selling her paintings and charcoal drawings not only in Boston but nationwide. Among her most beautiful works are the portraits she made of her daughter, Nancy Hale, in which she combined her maternal duties and her art (Fig. 2). Lilian worked from a home studio, minimizing the domestic disruption experienced by women who worked. She turned over her city studio to her unmarried friend Gretchen Rogers (1881–1967), another alumna of the Museum School who became one of Boston’s most talented figure painters.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Marion Boyd Allen (American, 1862–1941), Anna Vaughn Hyatt, 1915. Oil on canvas, 64 1/2 x 40 inches. Collection of the Maier Museum of Art, Randolph-Macon Woman’s College; Randolph-Macon Art Association, 1922.

|

Rogers’s Woman in a Fur Hat (Fig. 3) communicates all of the ingredients most valued by the proponents of the Boston School style of painting. The figure is carefully drawn, the composition is perfectly balanced, and the atmosphere is suffused with light. Rogers’s work exemplified the ideals of beauty that defined Boston painting. At the same time, the artist disguised the fact that she literally represented this iconic image—only by reading contemporary reviews does one learn that Woman in a Fur Hat is Rogers’s self-portrait. Such reticence was far from sculptor Anna Vaughn Hyatt’s (1876–1973) mind when Marion Boyd Allen (1862–1941) painted her portrait (Fig. 4). Allen, who also trained at the Museum School, captured Hyatt raptly absorbed in the creative process in her Annisquam, Massachusetts, studio. The sculptor assumed a customary pose, resting her foot on the stand that holds her model, holding her wire loop in one hand, and shaping her clay with the other. Allen remembered that Hyatt had asked her to repaint the arms in this portrait to display more accurately her muscular strength.6 Unconcerned with ideals of feminine beauty, Hyatt cared deeply about her image as a capable sculptor.

The 1929 self-portrait Algerian Tunic by Polly Thayer (b. 1904) (Fig. 5), a student of Philip Hale’s, combines visible expertise with a new self-confidence. Thayer does not seem passive but positive. Her hair is bobbed in the new style, she gazes at the viewer directly, and she holds her brush in midair, just about to use it. Thayer’s evident intellectual curiosity led her to explore a modern vocabulary in her later work, leaving behind the more traditional approach of many Boston painters. No matter what aesthetic choice they made, however, Thayer and her colleagues proved that a woman’s proper place could be

in a studio of her own.7

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Polly (Ethel R.) Thayer (b. 1904) with Self-Portrait: The Algerian Tunic 1927, August 13, 2001. Oil on canvas, 35 x 30 inches. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; private collection.

|

The exhibition is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston from August 15 to December 2, 2001. Drawn from the MFA’s holdings, other institutions, and private collections, the show includes works in a variety of media by forty-four talented artists and is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue.

The catalogue, with text written by curator Erica E. Hirshler, offers a compelling history of the lives and art of these women artists. As Hirshler notes, “There is very little recently published information on this group of artists. I became interested in studying them further after working on the MFA’s 1986 exhibition The Bostonians.” What came to light was how integral these early women artists were to the Boston art community, and how often their activities—exhibitions and studio life—were written up in local and international publications. “Some of their work was hard to find,” explains Hirshler, “but I hope this exhibition changes valuations on women’s art. These artists enabled the success of succeeding generations.”

Erica E. Hirshler is Croll Senior Curator of Paintings, Art of the Americas, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

- Greta [pseud.], “Art in Boston,” The Art Amateur 20 (January 1889), p. 28.

- William Rimmer to Ednah Cheney, March 28, 1864, quoted in Truman H. Bartlett, The Art Life of William Rimmer (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1882), pp. 42-43.

- A. Rhodes, “Views Abroad,” The Galaxy XVI (1873), p. 13, as quoted in Jo Ann Wein, “The Parisian Training of American Women Artists,” Woman’s Art Journal 2 (Spring/Summer 1981), p. 42.

- Greta [pseud.], “Art in Boston,” The Art Amateur 16 (January 1887), p. 28.

- Anna Lea Merritt, “A Letter to Artists: Especially Women Artists,” Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine 65 (March 1900), p. 467.

- M.J. Curl, “Boston Artists and Sculptors Talk of Their Work and Their Ideals,” XXV, Marion Boyd Allen, Boston Evening Transcript, May 29, 1921 (clipping, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library).

- More complete information about each of these artists can be found in the book from which this essay is drawn: Erica E. Hirshler, A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston 1870–1940 (Boston: MFA Publications, 2001).

|

|

|