|

|

|

|

|

|

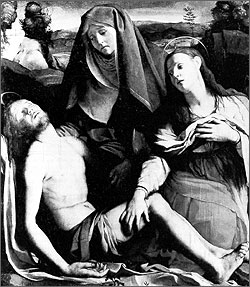

Fig. 1: The Dead Christ with the Virgin and Saint Mary Magdalene (also known as Pietà). Circa 1529. Courtesy of Uffizi, Florence.

|

The leading artist in Florence in the middle of the sixteenth century and court painter to the Medici ducal court throughout the 1540s and 1550s, Agnolo Bronzino (Monticelli 1503–1572 Florence) was the foremost exponent of Florentine Mannerism. His aristocratic portraits, religious pictures, and mythological scenes were greatly admired by his contemporaries. Indeed, the artist, architect, and commentator Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) lists the artist foremost among those who were still alive when he was writing his Lives: “Beginning with the oldest and most important, I shall speak first of Agnolo, called Bronzino, a Florentine painter truly most rare and worthy of all praise.”1

As a young boy, Bronzino was apprenticed to the Florentine painter Jacopo Carucci, called Pontormo (1494–1557), whose Mannerist style—characterized by an expressive and idiosyncratic pictorial language, incorporating strongly lit, agitated figures within a compressed pictorial space—was to be the major influence on his artistic development. He rose to become Pontormo’s chief pupil and assistant.

Bronzino achieved considerable renown as a portrait painter, counting among his subjects various members of the Medici family and ducal court as well as other Florentine noblemen, poets, and musicians. He also painted important altarpieces for the Florentine churches of Santa Croce, Santo Spirito, and Santissima Annunziata.

Colnaghi’s superb, newly discovered drawing is a preparatory study for one of Bronzino’s earliest works, the panel of The Dead Christ with the Virgin and Saint Mary Magdalene (also known as Pietà), in the Uffizi, Florence (Figs. 1, 2). The painting was commissioned in 1529 by the Florentine banker Lorenzo di Antonio di Bernardo di Giovanni Cambi (1479–1533) for his family chapel in the Florentine church of Santa Trinita.

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Study of the Dead Christ, circa 1529. Black chalk on paper, 12 3/8 x 8 5/8 inches. Private collection, France.

|

The present sheet is evidently an early idea for the pose of Christ as developed in the Uffizi picture, as there are numerous discrepancies between this drawing and the finished painting. The most prominent differences are the raised position of Christ’s head in the drawing, which is supported by the hand of the Virgin, and the placement of his left hand, held by another hand, which must be that of Mary Magdalene.

In the Colnaghi drawing, the figure of Christ is lit from the left, with his face in shadow. This was in fact Bronzino’s usual practice, as he invariably chose to illuminate his pictures from the left. Only three paintings in his entire oeuvre are not lit from the left, including the Uffizi’s Pietà. Perhaps the artist had learned his Pietà would be hung to the left of the Cambi chapel’s main door, thus illuminating the panel from the right.

Bronzino, like Pontormo, seems to have wholeheartedly adopted the practice of making studies from the posed model, judging from the relatively few drawings known today. The question of whether the Colnaghi drawing is a life study, however, has been a subject of recent debate among scholars. That the present sheet has every appearance of having been drawn from life is evident in the sensitive modeling of forms and the play of light on the features of the dead Christ. Conversely, the presence of the hands of the Virgin and Mary Magdalene argue against the drawing having been made purely as a life study. Catherine Monbeig Goguel has suggested that this sheet is not a life drawing per se, but may have been based on earlier, more spontaneous studies. She points out that the artist may have already been thinking about the integration of Christ into the larger composition through the light stroke of black chalk, indicating the rock he would lean against as well as the presence of the hands of the Virgin and Mary Magdalene.2

Less than thirty fully attributed drawings by Bronzino survive today, of which only a very few can be dated prior to 1540. The emergence of this previously unknown drawing and its relationship to one of Bronzino’s most important early works greatly adds to modern scholarship and to an understanding of the artist’s development as a draughtsman. However, quite apart from its art historical significance, this beautiful and intensely moving sheet is one of the very finest drawings by Bronzino to have survived. It is a notable addition to the corpus of sixteenth-century Florentine draughtsmanship.

Stephen Ongpin is Director of the Drawings Department at the London-based Old Master dealer Colnaghi, est. 1760. He has written and edited fifteen scholarly catalogues for the gallery, including publications for the gallery’s annual Master Drawings exhibition in July, and has contributed to a number of other publications.

|

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (Florence: 1568); translated by Gaston du C. de Vere (London: Everyman’s Library, 1912, 1996 ed., vol. II), p. 868.

- Catherine Monbeig Goguel, “Pour Bronzino: Un nouveau modele de Christ mort entre Pontormo et Allori,” in Marisa Dalai Emiliani and Francesco Di Teodoro, ed., In Onore di Andrea Emiliani (Bologna: Minerva, 2001, forthcoming).

|

|

|