|

| Home | Articles | Eighteenth-Century Sèvres in the Collection of Eleanore Elkins Rice |

|

|

Eleanore Elkins Rice was born in Philadelphia, the daughter of William L. Elkins, the prominent philadelphia businessman and philanthropist. Her marriage in 1883 to George D. Widener, the son of P.A.B. Widener, united two of America’s wealthiest families. Eleanore and George had a daughter and two sons; Harry, their eldest son, died with his father on the Titanic, and Eleanore subsequently donated money to Harvard University for a library in his name. It was at the dedication of the Harry Widener Memorial Library in June 1915 that she met Alexander Hamilton Rice, the son of a former Massachusetts governor, who was to become a professor of geographical exploration at Harvard. The couple was married later that year (Fig. 1). Eleanore Elkins Rice was born in Philadelphia, the daughter of William L. Elkins, the prominent philadelphia businessman and philanthropist. Her marriage in 1883 to George D. Widener, the son of P.A.B. Widener, united two of America’s wealthiest families. Eleanore and George had a daughter and two sons; Harry, their eldest son, died with his father on the Titanic, and Eleanore subsequently donated money to Harvard University for a library in his name. It was at the dedication of the Harry Widener Memorial Library in June 1915 that she met Alexander Hamilton Rice, the son of a former Massachusetts governor, who was to become a professor of geographical exploration at Harvard. The couple was married later that year (Fig. 1).

The Rices maintained two residences: Miramar, their spectacular home in Newport, and a townhouse at 901 Fifth Avenue in New York City. The Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer designed both Miramar and the New York townhouse, as he designed houses for many of America’s wealthiest families; he collaborated as well on the design of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1919–1928). The Parisian decorating firm of Carlhian and the art dealer Joseph Duveen consulted with Mrs. Rice in the furnishing of her various homes.

In 1937, Mrs. Rice bequeathed the drawing room of her New York townhouse and its furnishings to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Fig. 2). Part of this bequest was a collection of forty-one pieces of eighteenth-century porcelain made at the Vincennes/Sèvres porcelain factory in France. Founded at the château at Vincennes outside Paris in 1740, the factory was granted a privilege by Louis XV for “the manufacture of porcelain in the Saxon manner.” The factory was moved to Sèvres in the summer of 1756, possibly at the urging of the King’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour, who had friends among the shareholders of the factory and whose château at Bellevue was nearby. In 1759, the King, who had held a quarter of the factory’s stock since 1752, purchased the factory outright. In 1937, Mrs. Rice bequeathed the drawing room of her New York townhouse and its furnishings to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Fig. 2). Part of this bequest was a collection of forty-one pieces of eighteenth-century porcelain made at the Vincennes/Sèvres porcelain factory in France. Founded at the château at Vincennes outside Paris in 1740, the factory was granted a privilege by Louis XV for “the manufacture of porcelain in the Saxon manner.” The factory was moved to Sèvres in the summer of 1756, possibly at the urging of the King’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour, who had friends among the shareholders of the factory and whose château at Bellevue was nearby. In 1759, the King, who had held a quarter of the factory’s stock since 1752, purchased the factory outright.

All but four of the porcelain works from Mrs. Rice’s bequest feature two ground colors made famous at Vincennes/Sèvres in the eighteenth century: bleu céleste and rose. The bleu céleste ground color was invented in 1753 by the chemist Jean Hellot (1685–1766) and was used for the first time on Louis XV’s dinner service made between 1753 and 1755. The color was achieved using copper; its instability in the kiln made it one of the most expensive ground colors produced at the factory. The rose ground is found on some pieces dated from 1756 and 1757, though it was first recorded at Sèvres in 1758 when the painter Philippe Xhrowet (a. 1750–1775) was paid for its invention. Referred to as pompadour in England as early as the 1760s, this pink color came to be associated with Madame de Pompadour; in the nineteenth century the pink ground was often erroneously referred to as rose de Pompadour.

|

One of the most important influences at the factory from the late 1740s until the mid-1760s was the work of François Boucher (1703–1770), a prolific painter and draughtsman who perhaps more than any other artist defined the fine and decorative arts of mid-eighteenth-century France. Although little is known of the association between the factory and the artist, given Madame de Pompadour’s support of the porcelain factory and the fact that she was Boucher’s devoted admirer and patron, she may well have had a hand in introducing his work there. One of the most important influences at the factory from the late 1740s until the mid-1760s was the work of François Boucher (1703–1770), a prolific painter and draughtsman who perhaps more than any other artist defined the fine and decorative arts of mid-eighteenth-century France. Although little is known of the association between the factory and the artist, given Madame de Pompadour’s support of the porcelain factory and the fact that she was Boucher’s devoted admirer and patron, she may well have had a hand in introducing his work there.

Sèvres first employed Boucher’s designs as a source for sculpture, most notably the biscuit or unglazed porcelain figures that the factory began producing around 1751. The earliest reference to Boucher’s association with the factory is an inscription that reads “dessein de M. Boucher apartenant à la manufacture de Vincennes, le 23 aoust 1749” on the back of a drawing, which is still retained in the factory’s archives. This drawing was the source for the figure Le jeune suppliant, one of eight figures after Boucher produced at the factory and referred to as Enfants de Boucher. Subsequently, the factory used Boucher’s designs as the source for decoration painted in enamel colors on the porcelain.

The museum’s collection of Sèvres bleu céleste porcelain includes a vase, probably called, vase “à ruban” or “à couronne,” decorated with a scene after Boucher (Fig. 3). The vase bears the factory mark and the date letter for 1764, along with the mark of the miniature painter Charles-Nicolas Dodin (1734–1803), one of the most admired painters at the factory. The shape was probably designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis (ca. 1694–1774), père, a goldsmith and directeur artistique in charge of models at the factory. The vase’s decoration is based on a 1738 engraving by Pierre Aveline (ca. 1702–1760) titled La bonne aventure. The engraving, which is still in the Sèvres archives today, is after a cartoon painted by Boucher for a Beauvais tapestry series entitled Fêtes italiennes commissioned around 1730 and woven after 1736.1 The museum’s collection of Sèvres bleu céleste porcelain includes a vase, probably called, vase “à ruban” or “à couronne,” decorated with a scene after Boucher (Fig. 3). The vase bears the factory mark and the date letter for 1764, along with the mark of the miniature painter Charles-Nicolas Dodin (1734–1803), one of the most admired painters at the factory. The shape was probably designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis (ca. 1694–1774), père, a goldsmith and directeur artistique in charge of models at the factory. The vase’s decoration is based on a 1738 engraving by Pierre Aveline (ca. 1702–1760) titled La bonne aventure. The engraving, which is still in the Sèvres archives today, is after a cartoon painted by Boucher for a Beauvais tapestry series entitled Fêtes italiennes commissioned around 1730 and woven after 1736.1

|

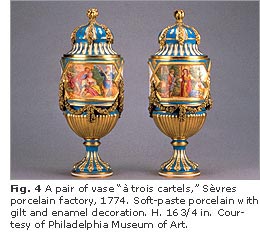

While never as popular a source as Boucher, decoration based on the work of the painter, draughtsman, and printmaker, Jean-Baptiste Le Prince (1734–1781) did appear on a number of vases made at the Sèvres factory in the 1770s and early 1780s. The museum’s collection includes a pair of these vases with bleu céleste ground (Fig. 4). The vases, called vase “à trois cartels,” bear the factory mark and the date letter for 1774.2

Le Prince made his reputation with paintings and engravings based on observations during his travels in Russia between 1757 and 1762.3 The scenes on the museum’s vases are based on two of Le Prince’s Russian sketches, Le Joueur de Balalaye and Le Moineau retrouvé. The vases bear the mark of the painter Fallot, who was active at the factory from 1764 to 1790. Fallot was known chiefly as a painter of birds, often in gilding, and occasionally flowers; it is therefore doubtful that he was responsible for the figural scenes on the vases. It is more likely that he painted the flowers in reserves on the backs of the vases or—given that his mark appears to have been fired at a low temperature, probably at the same time as the gilding—that he was responsible for the gilded decoration. Le Prince made his reputation with paintings and engravings based on observations during his travels in Russia between 1757 and 1762.3 The scenes on the museum’s vases are based on two of Le Prince’s Russian sketches, Le Joueur de Balalaye and Le Moineau retrouvé. The vases bear the mark of the painter Fallot, who was active at the factory from 1764 to 1790. Fallot was known chiefly as a painter of birds, often in gilding, and occasionally flowers; it is therefore doubtful that he was responsible for the figural scenes on the vases. It is more likely that he painted the flowers in reserves on the backs of the vases or—given that his mark appears to have been fired at a low temperature, probably at the same time as the gilding—that he was responsible for the gilded decoration.

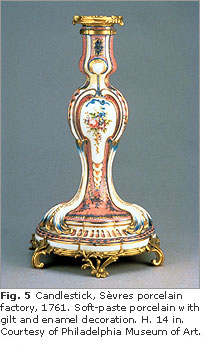

For a brief period between about 1761 and 1763 Sèvres produced pieces on which the rose ground color was largely covered by designs in blue. This decorative scheme is present in the museum’s collection of four extraordinary candlesticks that show the rose ground covered with an overall pattern of small blue spots (Fig. 5). The candlesticks, which are based on silver or gilt metal models, were probably designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis. The model is quite rare and does not appear in the Sèvres sales records. The candlesticks bear the factory mark and the date letter for 1761, along with the mark of the painter Jean-Baptiste Tandart (1729–1816), aîne. Tandart, who probably painted the flowers in reserves on the candlesticks, was a fan painter before joining the factory, where he was active primarily as a flower painter.

|

The eighteenth-century fascination with seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish masters was reflected at the Sèvres factory in its use of painted decoration in the form of rustic scenes, often after David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690). These scenes, whether after Teniers or not, are referred to in the factory records as Tenières. A garniture of three rose ground vase “hollandois” in the museum’s collection belongs to a group of this shape dated between 1759 and 1764. They are decorated with scenes taken from two engravings by Jacques-Philippe Le Bas (1707–1783) after paintings by Teniers (Fig. 6). The scene of a dancing couple and bagpipe player on the largest of the vases is taken from two sections of Le Bas’s print La quatrième fête flamande, which was announced in the Mercure de France in May of 1751; the scenes on the smaller vases are not identified. The museum’s vases are dated 1761, but bear no painter’s mark.4 The eighteenth-century fascination with seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish masters was reflected at the Sèvres factory in its use of painted decoration in the form of rustic scenes, often after David Teniers the Younger (1610–1690). These scenes, whether after Teniers or not, are referred to in the factory records as Tenières. A garniture of three rose ground vase “hollandois” in the museum’s collection belongs to a group of this shape dated between 1759 and 1764. They are decorated with scenes taken from two engravings by Jacques-Philippe Le Bas (1707–1783) after paintings by Teniers (Fig. 6). The scene of a dancing couple and bagpipe player on the largest of the vases is taken from two sections of Le Bas’s print La quatrième fête flamande, which was announced in the Mercure de France in May of 1751; the scenes on the smaller vases are not identified. The museum’s vases are dated 1761, but bear no painter’s mark.4

Prior to the 1760s, Sèvres produced only soft-paste porcelain. With the discovery of kaolin in France, the factory began to produce hard-paste porcelain as well. It continued making both types until 1804 when production of soft-paste porcelain was suspended. Sèvres began producing figures in hard-paste porcelain shortly after its introduction. The sole piece of hard-paste porcelain in the Rice collection is a figure of Gui-Crescent Fagon (1638–1718), chief doctor of Louis XIV and director of the King’s botanical gardens (Fig. 7). The figure was modeled at the factory in 1774 by Josse-François-Joseph Le Riche (1741–1812), a sculpteur, modeleur, and from 1780 chef des sculpteurs.5 Decorated in enamel, a process largely discontinued after biscuit porcelain was introduced in 1751, the figure bears the mark of Henri-Martin Prévost (ca. 1739–1797), primarily active at Sèvres as a gilder and probably responsible for the enamel decoration on the figure. Prior to the 1760s, Sèvres produced only soft-paste porcelain. With the discovery of kaolin in France, the factory began to produce hard-paste porcelain as well. It continued making both types until 1804 when production of soft-paste porcelain was suspended. Sèvres began producing figures in hard-paste porcelain shortly after its introduction. The sole piece of hard-paste porcelain in the Rice collection is a figure of Gui-Crescent Fagon (1638–1718), chief doctor of Louis XIV and director of the King’s botanical gardens (Fig. 7). The figure was modeled at the factory in 1774 by Josse-François-Joseph Le Riche (1741–1812), a sculpteur, modeleur, and from 1780 chef des sculpteurs.5 Decorated in enamel, a process largely discontinued after biscuit porcelain was introduced in 1751, the figure bears the mark of Henri-Martin Prévost (ca. 1739–1797), primarily active at Sèvres as a gilder and probably responsible for the enamel decoration on the figure.

The Rice collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art ranks among the great American collections of Vincennes/Sèvres porcelain. As with Mrs. Rice’s, most were formed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when America’s wealthy families were furnishing their palatial homes with the arts of eighteenth-century France. The taste for French objects, advanced by architects, decorators, and dealers such as Trumbauer and Duveen, was embraced by America’s wealthy, who found that the refined aesthetic and elegance of these eighteenth-century objects provided a suitable backdrop for their lifestyle.

|

|

Donna Corbin is the Assistant Curator in the European Decorative Arts Department at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

|

- The same scene appears on a pot-pourri, also painted by Dodin, in the collection at Waddesdon Manor in England. The museum’s vase was in the collection of Count A. D. Chéréméteff in St. Petersburg from the end of the nineteenth century until 1906, when part of his collection was exhibited by the dealer Asher Wertheimer in his shop on New Bond Street in London. The vase was subsequently purchased by Duveen Brothers and sold to Mrs. Rice.

- The shape is a rare one at the factory. It occurs only once in the factory sales records. On January 25, 1775 a pair of vases of this shape with a rouge ground color was sold to the Comte de Zernichev for 840 livres each.

- On his return to France, Le Prince became a member of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture and exhibited at the Salon for the first time in 1765.

- A number of painters at the factory are known to have painted scenes after Teniers, including Dodin, Jean-Louis Morin (1732–1787), and Antoine Caton (1726–1800), whose mark appears on a pair of vase “Duplessis à Enfants” in the museum’s collection.

- Given that Fagon died a half-century before Sèvres introduced the figure and that even in his lifetime he was not a universally admired personality, Le Riche’s choice is a puzzling one. A number of the more than thirty-seven figures attributed to Le Riche derive from contemporary theater, and it might be suggested this figure represents an unidentified character in the guise of Fagon. The figure is only mentioned once in the eighteenth-century sales records when on January 27, 1776 Madame Adelaïde, the daughter of Louis XV, paid 144 livres for an example.

|

|

|

|

|