|

n the second half of the eighteenth century, English ceramic manufacturers searching for appropriate decorative sources for their wares could turn to any number of design books for inspiration. One of the largest and most popular references was The Ladies Amusement; or, Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy, published by Robert Sayer around 1760. This manual contained upwards of 1,500 designs of “Flowers, Shells, Figures, Birds, Insects, Landscapes, Shipping, Beasts, Vases, Borders, &c.” n the second half of the eighteenth century, English ceramic manufacturers searching for appropriate decorative sources for their wares could turn to any number of design books for inspiration. One of the largest and most popular references was The Ladies Amusement; or, Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy, published by Robert Sayer around 1760. This manual contained upwards of 1,500 designs of “Flowers, Shells, Figures, Birds, Insects, Landscapes, Shipping, Beasts, Vases, Borders, &c.”

|

|

|

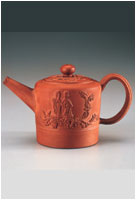

Fig. 1: Teapot by William Greatbatch, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1765. Red stoneware. Courtesy, Mr. and Mrs. Henry H. Weldon.

|

Sayer (w.1745–1794) intended The Ladies Amusement to be a design source for amateur artists and professional craftsmen. Though the title suggests that the volume was designed to guide genteel ladies in the fashionable hobby of japanning (decorative painting in imitation of oriental lacquer work), it was also meant to “be found extremely useful to the PORCELAINE, and other Manufacturers depending on Design.”1 It is clear that manufacturers agreed, for designs from The Ladies Amusement are found on a variety of materials, from textiles and silver to lacquer work and ceramics.

The first edition of The Ladies Amusement appeared sometime prior to February of 1760, when it was advertised for sale in The Gentleman’s Magazine for 18 shillings plain and 2 pounds, 2 shillings colored. A second edition was published a few years later, and a much-expanded third edition was published around 1775.

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Plate 175, The Ladies Amusement.

|

In addition to The Ladies Amusement, Sayer also published The Artist’s Vade Mecum and other collections of images, such as the “historical subjects, extremely useful for enamellers,” that inspired the work of potters.

The Ladies Amusement is a compilation of a variety of engravings from numerous sources. Some of the plates were likely used in previous publications and were probably already on hand in Sayer’s shop. Two of the most recognized artists who contributed to The Ladies Amusement are Jean Pillement, a French designer working in London who specialized in chinoiserie designs (fanciful European interpretations of Chinese design), and Robert Hancock, an accomplished engraver who also worked at the Worcester Porcelain factory.

Nearly every style and subject popular in the mid-eighteenth century is represented in The Ladies Amusement. The rococo, classical, and chinoiserie styles predominate. Flowers, shells, birds, and insects abound, reflecting the interest in the natural world that was prevalent in the period. Pastoral vignettes of country peasants at work and genteel ladies and gentleman cavorting in gardens also reflect this interest in nature and rural life emblematic of the period of enlightenment.

|

|

|

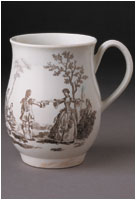

Fig. 4: Mug, Worcester, circa 1760–1765. Porcelain. Courtesy, Winterthur Museum. The scene, known as “the Minuet,” is attributed to engraver Robert Hancock and appears on Worcester porcelain in the mid-1760s, several years before it is included on plate 118 of the third edition of The Ladies Amusement, which was published around 1775.

|

Popular as a design source among ceramics manufacturers, some rare painted and molded designs are known.4 Staffordshire potter William Greatbatch used clusters of shells from plates 26 and 27 to decorate shell-molded tea and coffee wares, and from plate 175 he borrowed the image of two Chinese ladies positioned on a bridge5 for use as sprig-molded decoration on both tortoiseshell and unglazed redware tea and coffee pots6 [Figs. 1, 2].

Artisans most commonly referred to The Ladies Amusement for transfer-printed wares. Transfer printing on ceramics was developed in the 1750s. John Brooks, a Birmingham engraver, is credited with developing printing on enamel in 1751. By the mid-1750s Worcester potters introduced printing on porcelain, and in 1756 John Sadler of Liverpool began printing on delftware tiles.

Producers and consumers immediately embraced this new decorating process that allowed for the quick and easy reproduction of crisp, detailed images. Engraved copper plates could be used for either printing on paper or on ceramics. In fact it is likely that Robert Hancock of the Worcester porcelain factory engraved plates first for use on porcelain and later supplied them to Robert Sayer for inclusion in The Ladies Amusement.

An example of such transmission is a scene of a genteel couple dancing the minuet that appears on mugs and teapots made in the 1760s but that was not included in The Ladies Amusement until the third edition, published around 1758 [Fig. 4]. In addition to the Worcester pottery, the Chelsea, Bow, and Liverpool factories all integrated designs from The Ladies Amusement onto their porcelain.

|

|

|

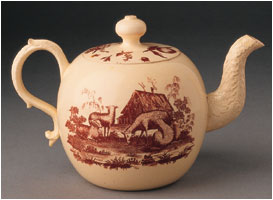

| Fig. 5: Teapot, Staffordshire, 1765–75. Creamware. Courtesy, Winterthur Museum. This teapot is typical of many printed wares in that the subjects are taken from a variety of sources. |

Designs from the book are even more common on English earthenwares. John Sadler and Guy Green of Liverpool turned to The Ladies Amusement for designs on their delft tiles, and potters in Staffordshire and Liverpool used the volume extensively

on creamware tea and dinnerwares. A teapot made in Staffordshire in the mid-1760s, for instance, has a group of sheep from plate 108 on one side and an insect from plate 8 on the lid [Fig. 5]. This piece is typical in that the other decorations, a Harlequin scene on one side and floral sprays and other insects on the lid, are taken from different design sources. It seems likely that potters had collections of individual engravings from a variety of sources that were chosen without regard for their origin.

|

|

|

| Fig. 6: Jug. Staffordshire, ca. 1810. Pearlware. Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; gift of B. Thatcher Feustman. One of the latest pieces known by this author decorated with scenes from The Ladies Amusement. The clusters of shells around the neck of this jug are taken from plates 26 and 27 [Fig. 7]. The Nanina was a brig active in the coastal trade between its home port of Philadelphia and the Caribbean. |

The Ladies Amusement continued to inspire ceramics decorationa half-century after its initial publication. One of the latest known pieces decorated with designs from the volume is a pearlware pitcher made in Staffordshire about 1810, probably for the owner or captain of the Nanina, a brig from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania [Fig. 6]. Below the handle is a winged female figure blowing a horn, seemingly a personification of Fame or Victory, from plate 122, and the neck is decorated with shells from plates 26 and 27 [Fig. 7]. By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, however, the rococo and chinoiserie designs of The Ladies Amusement had become old-fashioned, and ceramics decorators turned to new subjects and sources for inspiration.

Ron Fuchs is assistant curator of ceramics, Winterthur Museum, Gardens, and Library, Winterthur, Delaware.

1 Introduction, Robert Sayer, The Ladies Amusement; or, Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy (London, ca. 1762), reprinted by The Ceramic Book Company, Newport, England, 1966.

2 Vade mecum translates to “let me show you the way.” An instructional volume, it was first published in 1762. Other publications are included in Robert Sayer and John Bennett, Sayer and Bennett’s Enlarged Catalogue of New and Valuable Prints (1775), quoted in Timothy Clayton, The English Print, 1688–1802 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), p. 100.

3 A loose sheet, plate 145, from The Ladies Amusement, for example, survives in the papers of John Bowcocke, clerk of the Bow Porcelain Factory. Bernard Rackham, Catalogue of the Shreiber Collection (London: Board of Education, 1928), vol. I, p. 5.

4 An English delftware plate decorated with an image of dancer Nancy Dawson from plate 32 of The Ladies Amusement is illustrated in Michael Archer and Brian Morgan, Fair as China Dishes, English Delftware (Washington: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1977), p. 119.

5 The Chinese figures first appear in plate 118 of George Edwards and Matthew Darly’s New Book of Chinese Designs (London, 1754) and was copied by Sayer for inclusion in The Ladies Amusement. Such plagiarism was common. See Leslie Grigsby, “George Edwards and Matthew Darly’s Chinese Designs,”in The Magazine Antiques (February 1994), p. 303.

6 David Barker, “A Potter’s Amusement,” in Ars Ceramica (1989), pp. 35–40. See also Leslie Grigsby, The Henry H. Weldon Collection; English Pottery, 1650–1800 (New York: Sotheby’s Publications, 1990), pp. 58–59, and Peter Williams and Pat Halfpenny, A Passion for Pottery: Further Selections from the Henry H. Weldon Collection (New York, Sotheby’s Publications, 2000).

7 Pat Halfpenny, ed., Penny Plain, Twopence Coloured; Transfer Printing on English Ceramics 1750–1850 (Stoke on Trent: City Museum and Art Gallery, 1994), pp. 7–8.

8 Cyril Cook, The Life and Work of Robert Hancock (London: Chapman and Hall, 1948), pp. 57–8, 75.

9 Another example, for instance, is a ca. 1765 creamware bowl at the Winterthur Museum (accession number 61.932), decorated with four floral sprays, three of which are from plates 7 and 8 of The Ladies Amusement while the fourth is from an unknown source.

|