|

|

|

n 1853, art critic and social philosopher John Ruskin published The Stones of Venice. n 1853, art critic and social philosopher John Ruskin published The Stones of Venice.

In this, his seminal work, Ruskin proposed that all good design must be essentially Gothic in character. For Ruskin, the embodiment of this ideal was Venetian architecture of the fourteenth century as typified by the Ducal Palace on Saint Mark’s Square, what Ruskin would call “The Central Building of the World.” Venice was, he suggested, “The first of the states in Christendom,” and stood at the crossroads of passionate Northern Gothic and orderly North African influences, both of which, in their primary uses in religious structures, sought the glorification of God.

|

|

|

[Figure 1] Pair of hall chairs. William Morris (Designer), Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Painter): The Arming of a Knight (l.) and Glorious Gwendolen’s Golden Hair (r); Painted deal, leather and nails; Delaware Art Museum, acquired through the bequest of Doris Wright Anderson and through the F.V. duPont Acquisition Fund.

|

Ruskin was not writing for an unwilling or unprepared audience, for the Gothic style was well established in Britain. By the end of the eighteenth century, popular recognition was probably more closely associated with the “Gothik” fashion, known from design and pattern books, than with its historical British precedent. By the early nineteenth century, however, the Gothic Revival became the mode of church architecture in Britain. In fact, it was effectively legislated as such through its endorsement by subsidized church building programs. These associations were bolstered by the selection of Gothic as the style for the new Houses of Parliament in 1835, and the 1824 coronation of GeorgeIV, for which he wore Medieval attire, each powerful examples of the identification of Gothic Revival as a national style.

Much was written about Gothic architecture and literally hundreds of Gothic styles were identified, broken down by period, national origin, and even the degree of pointiness of their arches. Nor was Ruskin the first to theorize about the Gothic style. A.W.N. Pugin, the first of the great Gothic Revival architects, published The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture in 1841, which posed several arguments that Ruskin would echo a decade later: a building should first be functional; that decorative details should embellish the functional; and that materials and conditions should indicate methods of construction.

|

|

|

Armchair: Designed by Philip Webb for Morris & Co.; Circa 1870; Mahogany with upholstery (replaced).

|

Pugin was an architect and his work, however much he might have theorized about the social forces tied to architecture (Pugin was a convert to Catholicism, an act tied quite closely to his architectural theory), was written from the architect’s concrete perspective rather than the theoretician’s abstract one. What sets Ruskin apart, is that he was a non-architect using architectural theory to promulgate social doctrine.

In championing Gothic architecture, Ruskin was not merely a promoter of cusped arches or particular forms of tracery to which he devoted a significant amount of space, but the essence of his work was that good architecture embodied certain ideals in both their design and execution. In short, there was honesty in the organic and imperfect handiwork of a designer cum craftsman, as well as a straightforward quality in the design that precluded pretense.

|

|

|

|

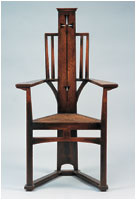

Clisset Armchair: Ernest Gimson; Circa 1918; Oak with

rush seat.

|

It was Ruskin’s assertion that this had been the case in the middle ages; great design was the product of a society that was not only capable of its execution, but also of its conception. The execution of one individual’s design by another was, for Ruskin, a form of enslavement, and was worse still when this form of serfdom tied men to machines. Preventing this was the philosophical purpose of Ruskinian Gothicism. If virtuous architecture could only be produced by free men, the same could be said of furniture and objects. In Ruskin’s terms, honesty in design was beautiful, and in beauty was truth such that beautiful objects were the product of moral means of production and were capable of infusing in their user the same morality.

The publication of The Stones of Venice in 1853 coincided with the arrival of William Morris at Oxford University. At Oxford, William Morris met Edward Burne-Jones and, through him, a group of other young men who would come to be fast friends. Morris had been sent to Oxford to study for the clergy, and this group, “The Brotherhood” as they were known, discussed entering a monastic order. Deeply influenced by The Stones of Venice, however, Morris and Burne-Jones determined instead to pursue work in the arts. To Ruskin, artistic labor was a form of divine glorification, so this change in direction was less radical or precipitous than it might at first appear.

|

|

|

Armchair: Designed by M.H. Baillie Scott; Circa 1900; Oak with leather.

|

Upon graduation, Burne-Jones moved to London and Morris was articled (apprenticed) to the renowned neo-Gothic architect George Edmund Street. Morris remained in Street’s office for eight months before changing direction and joining Burne-Jones in London with the intention of pursuing a career as an artist. The two young men took an apartment at Red Lion Square for which Morris, presumably unable to find commercially available furniture to his liking, designed a number of pieces including a simple round table, a large settle, and a pair of hall chairs (Fig. 1). The pieces were executed by a nearly anonymous cabinet-maker, Henry Price, who worked for the firm of Tommy Baker in Covent Garden. For assistance in the decoration of the chairs, Morris called upon Dante Gabriel Rossetti, himself already a well-known artist and a part of the pre-Raphaelite circle.

|

|

|

Armchair from the sussex range: Morris & Co.; The design attributed to Philip Webb; Circa 1865; Ebonized Beech Wood with Rush Seat.

|

The chairs Morris designed would never be singled out for their comfort. They were crudely executed, exposing joints that skilled cabinetmakers had long before learned to conceal. They utilize materials as though their maker had had neither the skill to cut finer boards nor the collected knowledge of hundreds of years of chair design and manufacture to know that the structural members could be much thinner and still be sound.

One hundred years before, at the height of the Georgian era, designers and craftsmen like Thomas Chippendale and designer-architects such as Robert Adam produced extraordinary pieces of furniture. In the elegance of their design and the skill of their execution they signaled the accumulated knowledge and refinement of generations. How was it that in the span of 100 years, which saw dramatic improvements in furniture-making technology and increasingly international influences on design, furniture design and manufacture could appear to have regressed so dramatically? How was it that a designer who must have known the work of Adam and Chippendale, Sheraton, Hepplewhite, and Hope, who must have had at least a passing familiarity with the designs of the ancient world, and who had access to the artisans or industry necessary to produce chairs every bit as sound as his predecessors, would produce such crude furniture?

Certainly, the design and execution of Morris’s furniture was deliberate. And if so, there must have been some purpose served by a chair on which it was uncomfortable to sit yet which so self-consciously articulated Ruskinian Gothic virtues. It was a polemical statement as much as a piece of furniture, the first in a series of applied aesthetic manifestoes that would impact virtually all design that followed. It was, in fact, the first Arts and Crafts chair.

|

|

|

|

Wyclif Chair: Designed by Leonard Wyburd for Liberty & Co.; Circa 1901; Oak, Walnut and Beech with Rush Seat.

|

While Morris’ chair for Red Lion Square should properly be identified as Arts and Crafts, so, too, should the work of Philip Webb, Ernest Gimson, M.H. Baillie-Scott, Leonard Wyburd, E.G. Punnet, and legions of others (see illustrations). Scholars and collectors, and even the artists themselves, have identified and labeled a movement, but on stylistic grounds the connections are, at times, quite tenuous. Arts and Crafts was not a movement that developed in a stylistically linear fashion, and therein lies the difficulty in describing the movement as a whole.

Where some designers, such as Morris in his early years, drew their inspiration from Gothic forms, others drew on the Georgian or Classical. Where many were steadfast in their adherence to British forms, others looked to the Continent, and still others took from the Far East. And where most looked to the past, others were enthralled with the industrial age. In construction, one group eschewed all use of machinery while another executed designs specifically for mass production (although most fell somewhere in between). And some produced for individual patrons while others for the burgeoning middle class.

|

|

|

Side chair (Bottom): Designed by E.G. Punnett for William Birch; Circa 1900; Oak inlaid with Ebonized Wood and Pewter and Rush Seat.

|

What tied them together was the philosophy that underlay their efforts. Before the Arts and Crafts in Britain was a style or a fashion it was a theory, an approach to design that underlay the life work of William Morris. It was first manifested in those few, early pieces of furniture designed for his own use. The products of the Arts and Crafts movement are the embodiment of the idea that people can shape and are shaped by their environment, by the products they encounter and use every day; that the right sort of design and production imbue both the maker and the user with a moral purpose. Or, in a larger sense, that design and craft are forms of artistic expression equal to the “fine” arts rather than simply statements of fashion.

John Alexander, Ltd., specializes in important works from the English and Scottish Arts and Crafts, Gothic Revival, and Aesthetic Movements as well

as a select group of early 20th century Continental designs. The gallery is

located at 10-12 West Gravers Lane, Philadelphia, PA 19118, tel: 215.242.0741

Photos courtesy of John Alexander Ltd., except as noted.

|

|

|