|

| Home | Articles | A Pair of Art Nouveau Copper- Inlaid Silver Compotires |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1a: Pair of compotiers. Tiffany & Co., New York, 1910–1916. Silver with copper inlays. H. 41/8”, Diameter Top 83/4”.

|

A recent discovery in the Tiffany & Co. (1837–present) archives has led to information about the production period, decorative process, and design directive for an elegant pair of silver compotiers1 now in a private collection (Fig. 1). This pair, dating from about 1910 to 1915, presents a case study that enhances our understanding and appreciation of early-twentieth-century Tiffany silver.

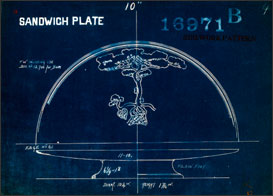

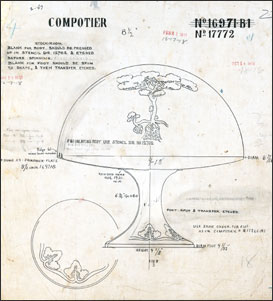

Compotiers were a part of the well-appointed tea table in the early twentieth century. In one of the etiquette manuals of the period, Manners and Social Usages, author Mrs. John Sherwood describes the customary accessories for an intimate tea that included a small table set with “a large tray, upon which are the tea-service and a plate of bread-and-butter, or cake, or both.”2 Mrs. Sherwood’s general term of “plate” would have included a range of serving pieces, among them a footed plate as defined on Tiffany’s archival patterns as a “sandwich plate” (Fig. 2), or a plate on a shaft, such as this pair, referred to on their pattern as a “compotier” (Fig. 3).

|

|

|

Fig. 1b: Detail of mark. Courtesy of a private collection; photography courtesy of Laszlo Bodo.

|

This particular pair of compotiers is embellished on the shafts and concave serving surfaces with bold silhouettes of conifers. Those on the serving surface are of the type that grow in such temperate areas as Long Island and California, where incessant strong winds force the branches and the major upright element, known as the leader, into horizontal growth and a flat crown.3 Their sinuous roots extend beneath a line demarcating the ground. Here the tree motifs are interpreted as lustrous copper inlays associated with the curvilinear phase of art nouveau. Their design further suggests a Japanese influence concurrent with the Arts and Crafts movement. Imagery from nature was an intentional response to the increasingly industrialized world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The tree motif was a prominent element, for example, in American paintings, photographs, posters, prints, watercolors, tiles, ceramics, and windows (Fig. 4). On the compotiers, the designer astutely located conifers of a triangular shape along the bottom of the shaft’s triangular outline, and placed those with a flat crown around the rim of the serving surface that they complemented.

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Hollowware Blueprint for Sandwich Plate, Pattern 16971B, ca. 1907. Pattern for sandwich plate, Tiffany & Co., New York, 1907. Paper. H. 101/2”, W. 133/4”. Copyright Tiffany & Co. Archives 2002. Not to be published or reproduced without prior permission. No permission for commercial use will be granted except by written license agreement.

|

Tiffany & Co. introduced this latter tree design on a sandwich plate (16971B)4 in 1907 (Fig. 2), three years before adapting it to a compotier. The compotier pattern (Fig. 3) of 1910 erroneously received the same number as the sandwich plates (subsequently corrected). The reason for the confusion may have stemmed from the directions on the compotier pattern indicating the “TOP – SAME AS – SANDWICH PLATE / 8H inch. 16971-B.” Tiffany & Co.’s archives also include a 1907 pattern for a sandwich plate with a different copper-inlaid tree pattern (Fig. 5). A completed plate is not known, and there is no evidence that the firm adapted that design to a compotier.

Marks on the underside of the compotiers (Fig. 1b) include an “M” to identify them with the administration of John C. Moore, who became president of Tiffany & Co. in 1907, a post he held until 1938.5 This particular copper-inlaid compotier pattern was first registered in July of 19106, in diameters of 8H and 10G inches. The earliest date stamped on the pattern for actual production is October 14, 1910 (Fig. 3). Although archivists did not always record production dates, other date stamps were found for 1911 and 1912. Not until 1913, 1914, and 1915 did the compotiers appear in Tiffany & Co.’s annual catalogues. There they are shown with other compotiers and are identified as “Silver inlaid with Copper.” They were priced in the small size for $70 and the larger size for $95. They are not in the 1916 or the 1917 catalogue; there was no catalogue in 1918; and no compotiers or sandwich plates are in the 1919 edition.7 Based on the evidence, this copper tree–inlaid compotier design was produced from 1910 through 1915. Although there must have been enough demand to warrant Tiffany & Co.’s continued production for a five-year period, only this pair and a now unlocated single example of this pattern with copper-inlaid trees are known.8

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Hollowware Blueprint for Compotier, Pattern 17772, October 14, 1910. Pattern for compotiers in Fig. 1, Tiffany & Co., New York, 1910. Paper. H. 14”, W. 163/16”. Copyright Tiffany & Co. Archives 2002. Not to be published or reproduced without prior permission. No permission for commercial use will be granted except by written license agreement.

|

Copper accents had been part of the decorative vocabulary on American silver since the late nineteenth century. From 1871 to 1882, for example, copper elements were applied to Tiffany’s silver in the Japanese taste.9 Copper accents enhanced silver from many shops, including Tiffany & Co., that were allied with the Arts and Crafts movement from the late 1890s until World War I, and copper inlays occasionally occur on Tiffany’s costly art nouveau silver contemporary with the compotiers.10

According to manufacturing notes on the pattern, the copper inlay was produced in a two-step process: The design on the plate surface was applied with a stencil and then etched, and the pattern on the foot was transfer-etched. Both methods involved using a pattern—stencil, silkscreen, or negative—that covered the area to be inlaid, around which a resist varnish was applied. When dipped in an acid bath, the areas not covered with the varnish would be etched away. The object was then dipped in a copper plating solution that filled only the recessed areas, as varnish covered the rest of the object, thus creating the copper inlays.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: The Gamble House entry, Pasadena, California. Windows designed by Charles Sumner Green (1868–1957) and executed by Emil Lange (1867–1934), 1908. Glass and teak. Courtesy of City of Pasadena and the University of Southern California; photography by Tim Street-Porter; courtesy of The Gamble House.

|

The man responsible for overseeing the design and production of the Tiffany & Co. copper-inlaid tree motifs was Albert Angell Southwick (1872–1960). Arriving at the company in 1903, he was soon appointed design director.11 Southwick had gained the respect of the artistic director, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), by July 6, 1906, when the firm’s employee ledger cites him in the shop at Forest Hills, New Jersey, working directly with Tiffany.12 Southwick continued as design director until 1919.13 He became comanager of the store in Paris in 1922, and two years later he received the additional responsibility of comanager for the London store. Southwick married Lilly Guichard of Paris, where they resided. He died there nine years after retiring in 1951.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Hollowware Blueprint for Sandwich Plate, Pattern 16971C, June 15, 1910. Pattern for sandwich plate. Tiffany & Co., New York, 1907. Paper. H. 1015/16”, W. 133/8”. Copyright Tiffany & Co. Archives 2002. Not to be published or reproduced without prior permission. No permission for commercial use will be granted except by written license agreement.

|

The talented designer and successful executive was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1872. At the age of 15 he enrolled in drawing classes at the Rhode Island School of Design. From 1888 until 1893 Southwick worked locally in silver factories—including a job as a designer for Howard & Son—to support his learning of engraving and other skills in Berlin, Dresden, and Vienna.14 In Paris, he studied drawing and painting at the L’École des Beaux-Arts and in the studios of Julian, Constant, and Laurens from 1898 to 1900. Southwick then may have returned to Providence until 1903.15

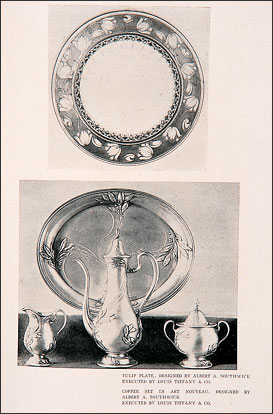

The Craftsman, the prominent magazine for aesthetic reform, endorsed Southwick and his career at Tiffany & Co. in the May 1906 “Artist and Silversmith-How One Man Worked to be a Successful Designer.”16 The complimentary text and the publisher’s endorsement of the Tiffany company suggest that the firm sponsored the article to promote Southwick and their silver under his direction. The author remarks that Southwick was in Europe “during the first flush of interest in the Art Nouveau movement” and was proficient in it.17 At the time the article was written, the “new art” promoted by the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900 was also in vogue in America. By the time the compotiers were first introduced in 1910, interest in the art nouveau style was declining and was passé by World War I.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Illustration of silver designed by Albert Angell Southwick (1873–1960) and executed by Tiffany & Co., is from The Craftsman (May 1906), v.10, no. 2: 179. Paper. H. 101/4”, W. 71/4”. Courtesy of The Winterthur Library: Printed Books and Periodicals Collection.

|

Louis Comfort Tiffany’s rapid promotion of Southwick, who was schooled in the art nouveau aesthetic, to design director was most likely a response to silver produced by their major competitor, Gorham Manufacturing Company (1831 –1981). Gorham had taken great strides with silver in the art nouveau style, and in 1897 it introduced the Martelé line, which won major accolades at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in Saint Louis in 1904 and continued in production until 1912.18 Though several pieces produced at Tiffany & Co. in the 1890s, among them the Magnolia vase of 1893 now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, include elements associated with the proto–art nouveau, the company did not fully embrace the aesthetic until L.C. Tiffany became design director and vice president of the company after the death of his father in 1902; within a year, Southwick was hired.19

Among the art nouveau silver designs appearing immediately after Southwick’s employment at Tiffany & Co. is a coffee service with naturalistic decoration overlaid on traditional mid-eighteenth-century forms, described as “applied so as to intensify, not mar, the beauty of line”20 (Fig. 6). The figures, animals, and plants on Southwick’s art nouveau silver are consistent with his academic training and, like the designs on the compotiers, are on simple and symmetrical forms that contrast the curvilinear and frequently asymmetrical shapes of Gorham’s Martelé silver.

With the onset of World War I, Tiffany & Co. abandoned the art nouveau aesthetic and moved in the direction of reviving European and American historic designs. Southwick’s departure for Paris in 1919, after the end of the war, further defined the end of the art nouveau influence at the firm. The compotiers represent the type of stylish design that Tiffany was producing in the early decades of the twentieth century. Perhaps other examples of compotiers and sandwich plates with copper-inlaid tree motifs will surface, adding to the legacy that is Tiffany silver.

Milo M. Naeve is the Field-McCormick Curator Emeritus of American Arts at The Art Institute of Chicago. The most recent exhibition and catalogue in his wide-ranging bibliography is 150 Years of Philadelphia Painters and Paintings for The Library Company of Philadelphia (1999).

|

1 Both of these compotiers bear central engraved monograms on the serving surface. The unidentified initials are an R flanked by L and G (Fig. 1).

2 Mrs. John Sherwood, Manners and Social Usages (New York and London, 1903), 222.

3 Interview, Milo M. Naeve with Dr. Tomasz Ani´sko, Curator of Plants, Longwood Gardens, Kennett Square, PA, Nov. 15, 2001.

4 The sandwich plate was available in two diameters, 8H inches and 10G inches. The pattern survives only for the larger size. Pattern 16971B is listed on page 280 of the MSS book recording patterns. The page is dated April 17, 1907.

5 After serving as president of the firm, Moore become chairman until 1947. Charles H. Carpenter, Jr., with Mary Grace Carpenter, Tiffany Silver (New York, 1984) mark no. 23, 252.

6 A duplicate pattern for the 8H inch compotier in the Tiffany archives is identified as “Reg [ular], Working Patt. [ern]” and bears a stamped date for April 15, 1910; the pattern for the 10G-inch size bears a blurred date that could be April 9, 1910; if the years are not in error, the dates may document trials before listing the patterns in the register on the page dated July 1910.

7 Though not recorded in catalogues or by date stamp, it appears that Tiffany reused the pattern for the form of this compotier as late as 1931, when a dated note on the pattern records a minor change in securing the shaft to the serving surface.

8 Tiffany scholar Janet Zapata recalls a now-unlocated copper-inlaid compotier offered for sale at Christies East, ca. 1996 (Interview, Milo M. Naeve with Janet Zapata, May 26, 1999).

9 Carpenter, Tiffany Silver, 185–198.

10 John Loring, Magnificent Tiffany Silver (New York, 2001), 232–233.

11 The date for his appointment is not documented in Tiffany & Co.’s surviving records, but his obituary in the Herald Tribune on June 2, 1960, cites it as “soon” after his employment.

12 Jane Zapata, The Jewelry and Enamels of Louis Comfort Tiffany (New York, 1993), 139.

13 Loring, Tiffany Silver, 233.

14 For the classes and work as a designer, Interview, Milo M. Naeve with Andrew Martinez, Archivist, Rhode Island School of Design, Jan. 9, 2002.

15 Biographical information about Southwick combines facts from obituaries in the New York Times and Herald Tribune, June 2, 1960; Anonymous, “Artist and Silversmith,” in The Craftsman 10 (May 1906): 177–78; Catherine W. Hart, “Family Sketches,” in A Brief Family History (France: Privately published, N.D.), 67–69. I am grateful to Louisa Bann for the obituaries, the Craftsman article, and introducing me to Miss Karine Coquelin, Paris, France, who kindly shared her information written about her great-grandfather by his descendants. Biographical information appears in Loring, Tiffany Silver, 226–233, but is not documented. I have annotated information that

differs from Loring.

16 The Craftsman, 176–179.

17 Ibid. 178

18 During these seventeen years, 4,800 pieces of Martelé were made. Charles H. Carpenter, Jr., Gorham Silver (New York, 1982), 221–252, especially 244–245, 249; L.J. Pristo, Martelé: Gorham Nouveau Art Silver (Phoenix Publishing Group, 2002).

19 Catherine Fuller, past curator of the Chrysler Museum and now at the Nelson-Atkins Museum, confirms my revision of a date for a child’s art nouveau Tiffany silver set from 1903 to 1907, when inscriptions document it as a gift to donor Frank A. Vanderlip, Jr. (Interview, Milo M. Naeve with Catherine Fuller, Dec. 31, 2001). This places the set under Southwick’s tenure. For previous research, see Mark A. Clark, Silver from the Chrysler Museum (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1989), no. 24, pl. 130, 66–67.

20 The Craftsman, 178. |

|

|