|

A nineteenth-century English-West Indian mahogany and caned settee and pair of chairs. Typical characteristics of colonial West Indian seating furniture are the bold proportions, heavily carved crest rails, and caned seats.

|

In the epoch of Caribbean history when its economy flourished largely due to its sugar cane crops, the plantation great houses and urban mansions of the colonial plantocracy were furnished in an elegant style distinctive to the West Indies. Made primarily in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when the islands’ sugar industry was most prosperous, this wonderfully rich furniture is unique to the sun-drenched region of floating lands bound by the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.

Cane sugar, often called “white gold,”1 along with tropical woods and crops of tobacco and cotton, were the basis of many a settler’s fortune. After Spanish explorers discovered the West Indies in the late fifteenth century, a continual battle waged between European nations for control of the resource-wealthy islands.

|

|

|

|

Above: Rose Hall is a significant great house in the Jamaican Georgian style. John Palmer, King George III’s representative to the Jamaican parish of St. James, built the house between 1770 and 1780. During the late eighteenth century, the islands of Barbados and Jamaica developed a domestic style that incorporated classical components of native English houses, adjusted for island living. To achieve maximum comfort in the tropical climate, breeze-catching verandas and balconies punctuated the formal symmetry of façades.

|

The English were the first to successfully challenge the Spanish claim to exclusive possession of the territory. In 1588, they defeated the Spanish Armada; by 1655, England had colonized Barbados, St. Christopher (now St. Kitts), Montserrat, Antigua, St. Lucia, Nevis, and Jamaica. Over the succeeding centuries, the main islands, thirty in all, were variously controlled by Spain, England, France, Holland, and Denmark, with domination of the individual isles sometimes changing.

Each colonizing nation contributed its own decorative influences to the archipelago. Plantation inventories from the 1640s and 1650s show that the early English-West Indian lifestyle was relatively comfortable. English planters at the time lived in two-to-three story houses and slept in mahogany four-poster beds. Their rooms contained luxury items like cushions and carpets; walls were hung with framed pictures and cupboards were filled with linen and pewter. Records show that one home possessed a library, another boasted a railed balcony and a polished marble floor.

|

|

|

|

| An unusual nineteenth-century English-West Indian armoire made from island courbaril wood with a high, scrolled pediment top; it is from the collection of Lord Glenconner on the English island of St. Lucia. Armoires and presses were preferable to chests of drawers because they allowed more room for clothes and linens to air, thus decreasing mold susceptibility in the tropical clime. |

|

A nineteenth-century West Indian mahogany games table from the English islands. Often made in pairs, games tables appear frequently in domestic inventories beginning in the late eighteenth century.

A Lutheran minister who visited the West Indies in 1740 remarked, “White women are not expected to do anything here except drink tea and coffee, eat, make calls, play cards, and at times sew a little.”

|

|

|

|

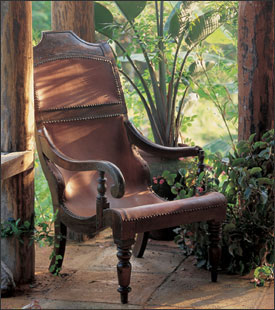

An example of a nineteenth-century Jamaican mahogany campeche (or campeachy) chair. This style of colonial chair always has a leather-upholstered seat rather than a seat that is hand-caned. The form is only found on the Spanish Antilles and the English island of Jamaica and is probably Spanish in origin.

|

|

An example of the work of the Jamaican cabinetmaker Ralph Turnbull, circa 1830,from a private collection in Jamaica. |

|

By the 1680s, the islands’ sugar industry had begun to financially reward the settlers. The nouveau riche then began to build and furnish elegant homes modeled on a lavish European lifestyle. In 1700, a missionary priest who visited Barbados, then England’s largest colony after Massachusetts and Virginia, commented on the plantation houses, “One notices the opulence and good taste in their magnificent furniture….”2

|

|

|

A nineteenth-century mahogany rocking chair from Jamaica’s Bellevue Great House. Although Bellevue was built in the 1750s, the chair is mid-nineteenth century with a Chippendale-style pierced back-splat typically found on colonial West Indian chairs from the English islands. Rocking chairs, prevalent after 1800, were often arranged in a social circle at the center of rooms to catch drafts from multiple windows.

|

The first great houses and urban mansions were adorned with pieces from Europe and North America. However, tropical heat, humidity, termites, and woodworm soon decimated many of these softwood furnishings and so planters charged local craftsmen, most of whom were African slaves or their descendants, with the task of creating furniture using the islands’ indigenous hardwoods. Virgin forests in Cuba, Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic), and Jamaica offered up a moderately hard and heavy mahogany (Swietenia mahogani) and other exotic woods such as cashew, grapefruit, coconut, and speckled bamboo. Roots and stumps of large trees were especially prized for their irregular wavy grain.

Few records exist for cabinetmaking shops in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries since most of the craftsmen were enslaved, anonymous, or illiterate. With rare exception, there is no tradition of signing, labeling, or dating island pieces until the twentieth century.

|

|

|

The dining room of Annandale Great House on Jamaica’s north shore is entirely furnished with late-eighteenth-and nineteenth-century island-made mahogany furniture.

|

While the heritage of these cabinetmakers in most cases was African, there are a few cases of immigrant European furniture makers, such as Ralph Turnbull, an Englishman active in Jamaica in the 1830s. Apart from those living on the Danish-controlled islands, Africans were discouraged or forbidden to seek formal education or training. Yet the need for a skilled labor force to maintain plantation great houses and island infrastructure provided opportunities in the woodworking trade. By the mid-eighteenth century, evidence shows that there were a large number of African slaves, many of whom later became free tradesmen, skilled in woodturning, carving, joining, and carpentry.

|

|

|

|

A bedroom in Rose Hall shows a nineteenth-century Jamaican-made mahogany four-poster bedstead and a regency Thomas Hope-inspired mahogany daybed with exceptional undulating dolphins and-shell carvings.

|

Craftsmen copied a succession of imported fashions from the planters’ homeland. In the early 1700s, they imitated the curvilinear shapes of the Queen Anne style. By the mid-eighteenth century, Georgian influences prevailed; the designs of Thomas Chippendale (1718–1779) were especially embraced on the islands. As a result, pierced splats lightened the look of chairs previously made with solid backs, and the straight Marlborough leg was incorporated into stylish furniture designs. In the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries, neoclassical forms such as serpentine-front sideboards were introduced, and legs became tapered. The more ornate regency (1811–1820) and empire (1804–1820) styles followed, after which revival fashions continued into the twentieth century.

Throughout the development of island furniture design, African-West Indian craftsmen’s copies of imported pieces became progressively less exact and increasingly more interpretative. They altered imported styles by adding decorative elements derived from African motifs and from the flora and fauna of their island surroundings, adding twist-and-ring turnings, stylized carved palm fronds, pineapples, banana leaves, sandbox and nutmeg fruits, and zoomorphic forms. They carved and turned these elements using copious amounts of wood for the bold, grand proportions evident in even the most graceful pieces.

|

|

|

|

| An early-nineteenth-century English-inspired sofa table is part of the collection at the circa 1750 Good Hope Plantation great house on Jamaica. The oil painting by Joseph Bartholomew Kidd (English, 1818–1889) shows the plantation in the nineteenth century. The floors are made of indigenous wild orange wood. |

|

Typical in a West Indian residence was the mix of island-made and imported furniture. In this private great house, the dining room includes an English mahogany table made by Benjamin Palmer Titter (active 1799–1830) of London and Norwich, circa 1810–1820. It bears a brass plaque on each end that reads, “The New Constructed Occasional Table/by B. P. Titter/Inventor and Manufacturer.” The accompanying mahogany chairs are also nineteenth-century English pieces.

A North American mahogany sideboard (circa 1840) sits below an English girandole mirror circa 1820. An early-nineteenth-century colonial West Indian mahogany cupping table resides between the windows. The English chandelier is circa 1820. |

|

West Indian craftsmen also reinterpreted furniture forms in order to adapt them to the tropical climate. Four-poster beds were constructed with high bases to catch window drafts. To facilitate airflow, a lightweight, flat-reed woven caning was used for seating.

|

|

|

Cover of Caribbean Elegance.

|

Planter’s chairs were a specialized Caribbean form made with very long arms so that the tired gentleman-planter could elevate his swollen feet and more easily remove his boots.

On the English Caribbean islands, colonial furniture was a blend of the quintessence of imported North American and English styles with vernacular African-West Indian decorative motifs and designs. The result is a distinctive West Indian furniture style whose vigorous lines bespeak a subtle opulence and casual elegance.

|

|

|

| A painting by Camille Pissarro (French, 1830– 1903) of the north shore of St. Thomas. Now part of the U.S. Virgin Islands, St. Thomas was once briefly governed by the English. |

Michael A. Connors, Ph.D., is a noted scholar of West Indian decorative arts and furniture. He teaches a course on Caribbean furniture at New York University and has designed two lines of colonial-inspired furniture for Baker Furniture Company. His recent publication Caribbean Elegance (Abrams, 2002) is an interiors and antique furniture book that will inspire antiques aficionados, designers, travelers, and anyone who has ever had an interest in the Caribbean islands. The writer lives in New York City and St. Croix.

Based in New York City, Bruce Buck is a highly regarded photographer of interiors, architecture, and decorative arts. His work has appeared in numerous books including Caribbean Elegance as well as magazines such as Architectural Digest, House Beautiful, and Southern Accents.

|

|

|