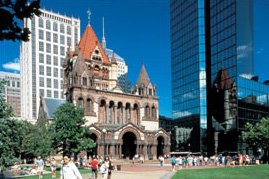

Boston's Trinity Church: Celebrating 125 Years

Trinity Church, which annually draws over 100,000 visitors from around the world to Copley Square in the heart of Boston, Massachusetts, stands as an enduring icon of the city and a monument to the years after the Civil War when urban design and architecture flourished in the United States (Fig. 1). Within a decade of its completion in 1877, architects hailed the church as an American masterpiece, and nearly one hundred years later, in 1971, it was designated a National Historic Landmark. Trinity is also the only church in America to be listed on three separate occasions as one of the ten most significant buildings in the country.1 In celebration of the 125th anniversary of the dedication of the building, the parish has undertaken a major capital campaign begun in February 2002. The project includes work to protect the murals and many of the stained-glass windows, which will be restored to their original brilliance. Major structural changes will also take place.

| |

| Fig. 1: Trinity Church, Boston, Mass., 1872–1877, H. H. Richardson, architect (1838–1886). Courtesy of Trinity Church; photography by Peter Vanderwarker. |

An Episcopal church, Trinity is home to a thriving urban parish that was founded in 1733 as part of the Anglican Communion. While the specific activities engaged in or sponsored by Trinity Church have changed over the centuries, it has remained closely linked to the city. One such example of this union occurred early in the history of the parish when a difficult and decisive decision was made shortly after the beginning of the American Revolution. Established as a colonial outpost of the Church of England, the parish committed a treasonous act when it elected to omit prayers for King George III and the royal family from the liturgy, siding instead with the patriotic cause. As a result, it was the only Anglican church to remain open in Boston throughout the war.

What visitors find when they come to Trinity Church is a rugged and commanding structure, built of granite and sandstone, massed around a great central tower and designed to command attention from every perspective. The church stands in one of the most successful urban spaces in the country, the vital living center of Boston’s Back Bay. Next door is the sleek and elegant mirrored glass of I.M. Pei’s John Hancock Tower, considered one of the great architectural accomplishments of the twentieth century. The reflection of the church in the façade of the tower has become a symbol of Boston’s ability to retain the best from the past while it welcomes new styles and ideas. Across Copley Square stands the Boston Public Library—itself considered one of the great examples of nineteenth-century architecture—designed by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White, and decorated with murals by John Singer Sargent.

| |

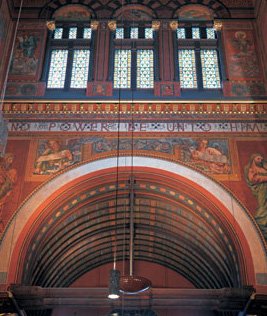

| Rugged stone work on the exterior reflects a Romanesque aesthetic and stands in contrast to the warmth of the interior of the church. Courtesy of Trinity Church; photography by Peter Vanderwarker. |

The present building is the third church built for the Trinity parish in Boston. By the 1860s, the congregation had outgrown its church. In addition, Trinity Church was then situated in what is now known as Downtown Crossing, an area that was fast becoming a commercial district, and one that the parish felt was not a fitting setting for their church. Under the direction of its dynamic rector, the building committee acquired property on ground newly created from land fill, in the hopeful expectation that the area would become a prominent section of the city, which it subsequently became. This decision to move coincided with an incredible explosion of creative energy in the fields of art and architecture across America following the Civil War. Trinity Church is a tangible symbol of this age of optimism, creativity, and new-found wealth.

Trinity Church represents the collaboration of three comparative youngsters who were all in their thirties when the church was built: Trinity’s rector, the Reverend Phillips Brooks (1835–1893), had a national reputation as one of the great preachers of his day;2 but architect Henry Hobson Richardson (1838–1886) had yet to make his name in the field of architecture; and artist John La Farge (1835–1910), known for his easel painting, had yet to be awarded a significant mural painting commission. Parishioner Robert Treat Paine (1835–1910), who served as chairman of the building committee, was also a young man, and as a result of this project was inspired to become one of Boston’s leading philanthropists.

|  | |

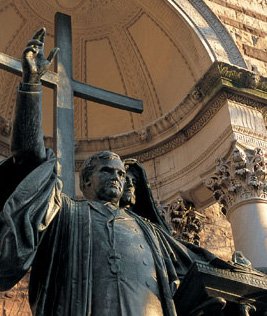

| Left: Fig. 2: The interior tower of Trinity Church, decorated with murals by John La Farge (1835–1910). Courtesy of Trinity Church; photography by Jim Scherer. Right: Fig. 3: A statue commissioned by the citizens of Boston to honor Phillips Brooks, Copley Square, Boston, Mass., 1909, carved by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907); base by McKim, Mead and White. Courtesy of Trinity Church; photography by Anton Grassl. | ||

Together, Brooks, Richardson, and La Farge conceived of a church that turned away from the austere Gothic styles deemed to be the proper idiom for churches at the time. Instead of long aisles and numerous columns that encumbered the view of the altar, this new church was designed to gather the congregation around the pulpit, to underscore the importance of preaching in the service. This meant breaking with precedents set in Europe that determined the “proper” style for a wide range of public buildings—especially churches. Trinity Church signified a new direction; one that drew inspiration from earlier architecture, yet was demonstrably fresh. It remains the prime example of the only American style to be named for its creator (Richardsonian Romanesque) and the first style from America to be copied abroad. And if Trinity was designed as an alternative to European Gothic designs, it also represented a dramatic alternative to the unadorned simplicity of a traditional New England village church with its white walls, stark altar, and plain windows.

| |

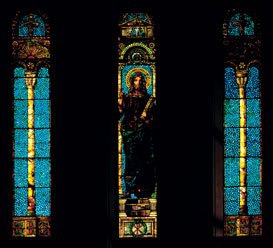

| Fig. 4: Christ in Majesty by John La Farge (1835–1910), 1883. Stained glass. Courtesy of Trinity Church. Photography by Peter Vanderwarker |

To enter through the great wooden doors from Copley Square into the narthex of Trinity Church is to be enfolded in a warm and richly decorated interior unlike any other American church built before it. In contrast to its rocky brown sandstone and granite exterior, the inside is awash in jewel-like colors. Warm wood elements accent the space that soars overhead, articulated by semicircular arches. The walls of the sanctuary are a rich red, and elaborate murals cover the upper reaches of a great central tower that soars more than 100 feet above the church floor (Fig. 2). John La Farge was the artist responsible for the majority of the mural painting, though members of his team were also involved. Among them was Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907), who painted for La Farge before he began the work that earned him renown as one of the great sculptors of his age. Saint-Gaudens’s commemorative statue of Phillips Brooks stands on the northwest exterior side of the church (Fig. 3).

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 5: The Resurrection by John La Farge (1835–1910), 1902. Stained glass. Courtesy of Trinity Church. Right: Fig. 6: The New Jerusalem by John La Farge (1835–1910), 1884. Stained glass. Courtesy of Trinity Church. | ||

| |

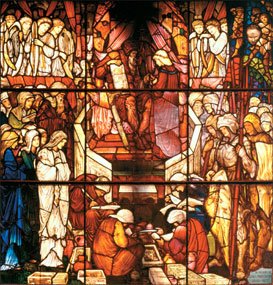

| Fig. 7: David’s Charge to Solomon by Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), 1882. Stained glass. Courtesy of Trinity Church. |

The building was designed in the form of a Greek cross, with four arms of approximately equal depth radiating from the central crossing under the tower. As the structure of the church rises, it becomes more complex with arches and inset windows. Over the west balcony, gilded decorative organ pipes frame Christ in Majesty (Fig. 4), one of five stained glass windows executed by La Farge for the church, which has been described by some experts as the most important work of stained glass art in the United States. Always an innovator, rather than combine irregularly shaped panes of glass, as in traditional windows, La Farge used golf ball-sized glass rounds in rich shades of blue, for the background of the Christ figure, which yield an even appearance that catch and radiate light.

Two windows by La Farge in the west wall of the north transept further represent his innovative use of glass. He pioneered, with great sophistication, the layering of opalescent glass to achieve an unprecedented visual richness and a sense of three-dimensional space. Among those he influenced was a young artist in his studio named Louis Comfort Tiffany, who went on to use many of the techniques pioneered by La Farge. In addition to La Farge’s talents, these windows also demonstrate the need for the work of preservation now set to begin. In the early 1990s, The Resurrection (Fig. 5) was restored, and now displays the full glory of color and complex, layered style that marks La Farge’s work. By comparison, its companion, The New Jerusalem (Fig. 6), part of the present campaign to restore the windows, is dark; obscured by over a century of pollutants.

| |

| Fig. 8: A variety of carved images adorn the pews of Trinity Church, many designed by H. H. Richardson (1838–1886). Black walnut. Courtesy of Trinity Church; photography by Peter Vanderwarker. |

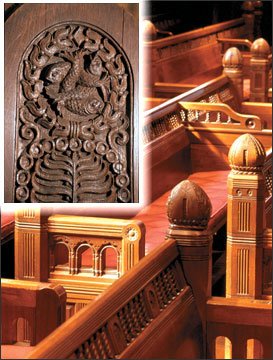

Other windows in the church offer an extraordinary survey of the art of stained glass. Works designed by English artist Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) and constructed in the workshop of William Morris of London fill the center wall in the north transept and can also be seen in the baptistery (Fig. 7); a series of windows by the French firm of A. Oudinot illuminates the south transept. Local artists are also represented, including Margaret Redmond (1866–1948) and Sarah Wyman Whitman (1842–1904). Among the original carved elements are the woodcarvings on pews and other furnishings in the church. Craftsmen of great skill wove a richly inventive vocabulary of sacred and secular designs and symbols into the interior of the building (Fig. 8), continuing the theme of fine stone carving that decorates the exterior of the church. Recent archival work has uncovered some pieces of the original wood furniture and furnishings that were designed under the aegis of H. H. Richardson and later removed from the sanctuary. Some items had been put into storage, while others were given to churches in the area. The original communion table continues to serve, for example, but as an altar in a nearby town.

One aspect of the building that has had a major impact on plans to renew and expand is the special circumstances of the real estate it occupies. Back Bay was created by filling in tidal mud flats and marsh to gain more space for the city. As a result, the church’s structure is supported by approximately 4,500 wooden pilings buried beneath the ground, clusters of which support great granite pyramidal “elephant feet” that are visible in the church undercroft, and in turn support the great central tower. In order to gain needed commons and forum space, room must be created between the floor above and the pilings below, and the project has to be designed so as not to interfere with the ground water that serves to preserve the pilings. This necessary space requirement presents the challenge of how to complete major construction without threatening the integrity of the historic structure.

| |

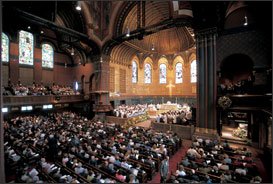

| Fig. 9: More than 2,000 people worship each week at Trinity Church at seventeen services offered through the week. Courtesy of Trinity Church; photography by Peter Vanderwarker. |

The efforts to preserve the church are the result of thousands of hours of thought, scrutiny, collaboration, and design by a team of parishioners and professional partners. Besides working to maintain, preserve, and expand on the riches of the building, another focus is on sustaining the active and full life of the 3,800-family parish—which includes seventeen services held each week, from Monday morning prayer through to the six o’clock service on Sunday evening—despite the presence of trucks, excavation equipment, and the ongoing work (Fig. 9). Even so, the stress and effort of renewal seem reasonable and appropriate. Members of the parish and the wider community of people who cherish this unique structure built to the glory of God—and which stands as a tribute to an age of creative achievement and extraordinary self-confidence—know that the result will be a building secured for future generations to discover and embrace.

1. What is now the American Institute of Architects bestowed these honors in the 1880s, 1950s, and 1980s.

2. Brooks came from a well-established Boston family of educators and ministers, and was one of the most significant preachers in the history of America. Brooks served as rector of Trinity Church, Boston, from 1869 through 1891, having previously led the Holy Trinity Church in Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square.

David Trueblood is Director of Communications at Trinity Church. A former journalist, he earned degrees in History and Urban Studies as an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania and as a graduate student at Harvard University.

This article was originally published in Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|