|

|

Frederic Church (1826–1900), The Icebergs, 1861. Oil on canvas, 64-3/8 x 112-1/2 inches. Courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Texas (anonymous gift).

|

|

|

From polar ice floes by Frederic Church to wintry Manhattan

streets by Guy Wiggins, snow scenes are heating up today’s art market.

|

|

|

|

William Bradford’s The Arctic Regions (London: 1873). Limited edition

of 350 copies. Original full-morocco presentation binding. Courtesy of Hyland Granby Antiques, Hyannisport, Mass.

|

In 1979, Frederic Church’s (1826–1900) Arctic masterwork The Icebergs sold at auction for $2.5 million, two and half times the highest hammer price achieved for an American painting up to that time.1 The momentum created by the sale continues to this day, evidenced by the ever increasing demand for landscapes by American artists. Among those whose popularity has surged in the last few decades, are several American painters known for their snowy renditions, who have come to the forefront of scholarship and market interest.

|

|

|

| Guy C. Wiggins (1883–1962), Stormy Day at the Plaza. Oil on canvas board, 12 x 16 inches. Courtesy of The Greenwich Gallery, Greenwich, Conn. |

Cold-weather scenes have at times been difficult sales, even for established artists. The Icebergs elicited widespread adulation from the public and press but failed to find a buyer when Church first unveiled the painting in New York and later in Boston. Some critics pointed out that there was no link to humanity in the inhospitable ice-scape. The year was 1862, and Church was at the height of his career as the most successful landscape painter of the Hudson River school. However, economic jitters at the start of the Civil War were building just as the painting, which Church had at first pointedly titled The North, debuted.

|

|

|

|

Jonathan Fairbanks (b. 1933), The Spring Thaw, 2002. Oil on board, 18 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Haley & Steele, Boston, Mass.

|

In his contribution to Eleanor Jones Harvey’s recent book The Voyage of the Icebergs, Frederic Church’s Arctic Masterpiece (Yale, 2002), Church expert Gerald Carr explains that the painting reflected a Victorian fixation with the “adventure and eye-popping spectacle” of the vast and uncharted polar frontier. More than a representation of a magnificent frozen flotilla, The Icebergs spoke of mid-nineteenth century politics and exploration, and Church, who was an ardent Unionist and a member of the American Geographical and Statistical Society, saw the Arctic as an extension of the American North.

|

|

|

Walter Launt Palmer (1854–1932), Snow Clad Fence. Watercolor and gouache, 20 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Avery Galleries, Haverford, Penn.

|

In order to improve on the work’s salability, Church changed the title to The Icebergs, added a broken mast to the composition—a romantic reminder of man’s presence, and perhaps his demise, in the merciless northern sea—and took the work to England. Here, it was Church’s status as an international celebrity-artist that ultimately connected him with a buyer, the wealthy British railroad magnate Edward William Watkin (1819–1901). The Icebergs then dropped from sight, its whereabouts unknown. After hanging in a seldom-used stairwell at Watkin’s estate outside of Manchester between 1865 and 1979, the painting’s rediscovery and subsequent auction made headlines. The purchasers, private collectors from Texas, immediately gifted the work to the Dallas Museum of Art on the condition of anonymity, and since then, The Icebergs has become an iconic American work in the snow-and-ice genre, exhibited widely and recently reinstalled at the museum.2

|

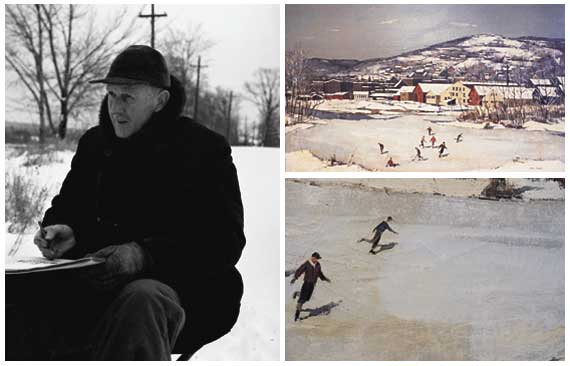

Photograph of Paul Sample at work on Millers River, January 6, 1952. Courtesy of a private collection. Photograph by Earl Harris. Right top: Paul Sample (1896–1974), Millers River, Rodney Hunt Machine Company, Orange, Massachusetts, 1952. Oil on canvas, 30 x 48 inches. Courtesy of a private collection. Photograph taken by Anne O’Connor prior to cleaning.Right bottom: This detail of Sample’s Millers River reveals the work’s true blue-gray ice color in a partially cleaned area during the process of “aqueous grime removal.” Photograph by conservator Anne O’Connor.

|

|

|

|

|

Frank Weston Benson (1862–1951), Little Brook, 1934. Watercolor, 19-1/2 x 24-1/2 inches. Private collection courtesy of Brock & Co., Carlisle, Mass.

|

While the splendor of ice floes was just one of Church’s subjects, it dominated the oeuvre of New Bedford, Massachusetts artist William Bradford (1823–1892). He journeyed to Nova Scotia, Labrador, and Greenland several times, creating hundreds of studies, which he followed with atmospheric studio pictures. In 1869, Bradford led an expedition to document the area in photographs for his book Arctic Regions (London: 1873). He wrote in his introduction that the purpose of his trip on the whaling steamer Panther was “to study Nature under the terrible aspects of the Frigid Zone.” To that end, Bradford brought along two photographers whom he artistically directed in depicting Inuits, icebergs, and the party’s own icebound whale ship.

|

|

|

Guy C. Wiggins (1883–1962), Manhattan Winter, 1934. Oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches. Courtesy of Spanierman Gallery, N.Y.

|

Completely intact copies of Arctic Regions include 141 original albumen photographs. Hyannisport, Massachusetts maritime art and antiques dealer Hyland Granby Antiques has one

of these 25 by 20 inch volumes, which will be offered at the January 2003 Winter Antiques Show in New York City. Bradford’s work will be the subject of a major retrospective in the artist’s hometown at the New Bedford Whaling Museum from May 22 to October 26, 2003.

For the most part, Bradford, as well as Church and other Hudson River school painters, trekked outdoors for inspiration and to sketch, but created their finished ice-and-snow works in the comfort of heated studios. Many impressionists from the late nineteenth century to the present have also occasionally opted for a less-than-plein-air experience. Contemporary impressionist Jonathan L. Fairbanks often paints directly from nature, but also relies on field sketches and sometimes photographs to aid his final studio works. The reason is simple logistics: paints are less fluid in frigid temperatures, time is needed to execute details (Church sometimes spent months and even years on one canvas), and for important Hudson River school works, canvasses were often of a monumental size not conducive to on-location painting. Church’s Icebergs measures 6 by 9 feet and was finished a few years after he’d made close to a hundred sketches for it during his visit to the Arctic on a chartered schooner in the summer of 1859.

|

Guy C. Wiggins (1883–1962), Winter Storm on Central Park South. Oil on canvas, 28 x 42 inches. Courtesy of Cherry Rainone, Rainone Galleries, Arlington, Texas.

|

|

|

|

|

Guy C. Wiggins (1883–1962), Light of the Morning, 1922. Oil on canvas, 34 x 40 inches. Courtesy of The Cooley Gallery, Old Lyme, Conn.

|

“This New England painter goes after Nature in the rough,” Irma Whitney, art editor of the Boston Herald observed about Aldro Hibbard (1886–1972).3 His landscapes captured Vermont, New Hampshire, Cape Cod, and the seaside art colony of Rockport, Massachusetts, in every season. Hibbard’s snowy Rockport in Winter, exhibited at the 1931 National Academy of Design’s annual exhibition in New York City, won him his highest honor, the First Altman Landscape Prize for $1,500. Today, his winter works bring between $10,000 and $50,000.

Hibbard addressed the challenge of capturing snow with careful observation. “There can be numerous color values in a single snow bank. It is never dead white!”

Walter Launt Palmer (1854– 1932), the son of sculptor Erastus Dow Palmer and a student and studio mate of Church’s, also saw the kaleidoscope of colors reflected in snow. His late-nineteenth-century oils and watercolors of New England in winter—as popular today as in his own time—reveal a lively palette of pinks, greens, and purples, but Palmer’s signature blue shadows, an impressionist device then just recently introduced, distinguished his snow scenes. He successfully bridged two styles—a high-keyed, impressionist color palette with a precisely-rendered, Hudson River school aesthetic.4

|

|

|

|

Johann Berthelsen (1883–1969), Wall Street, Old Trinity Church. Oil on board, 12 x 9 inches. Courtesy of Roughton Galleries, Dallas, Texas.

|

So were these snow painters—exploring uncharted territories and sketching in icy temperatures—the more intrepid of the artist breed? Many were certainly active winter sportsmen. The New Hampshire artist Paul Sample (1896–1974) loved to ski and ice skate and always took his sketch book along on these winter outings. Impressionist Frank Benson’s (1862–1951) passion for winter duck hunting became the subject of his oils and watercolors as did his observations of icy brooks and chickadees alighting on frozen branches.

Summer art colonies inspired a few artists to stay year-round to paint scenery. Edward Willis Redfield (1869–1965) established the impressionist tradition in New Hope, Pennsylvania, with his winter landscapes. In the early twentieth century, Provincetown, Massachusetts, hosted thousands of established painters and art students in the summer; some stayed on to paint through the bleaker months including Dodge MacKnight, C. Arnold Slade, E. Ambrose Webster, and John Whorf.

A longtime resident and teacher in the area of the art colony in Old Lyme, Connecticut, Guy C. Wiggins (1883–1962) is best known for his snowy impressionist Manhattan scenes. While his work entered the Metropolitan Museum of Art when he was just twenty, and numerous awards and memberships in prestigious New York art clubs followed, Wiggins’s style gradually lost favor. The Three Landscapists, a 1978 retrospective at the New Britain Museum of Art in Connecticut that covered the work of Guy C., his father Carlton (1848–1932), and son Guy A. (b. 1921), brought Wiggins back into the spotlight momentarily, but his comeback on the market has been noticeable only over the past ten years. “Prior to 1992, it was hard to find a Wiggins at the top East Coast galleries,” says one dealer. “And then dealers and collectors began to appreciate his works’ winning elements—atmospheric snow effects, an impressionist palette, and recognizable New York landmarks.”

|

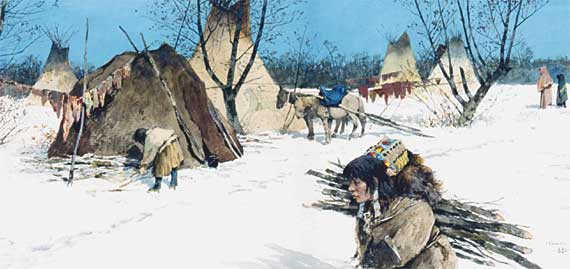

Henry F. Farny (1847–1916), Winter Encampment of the Crow Indians, 1882. Watercolor and gouache on paper, 16-1/2 x 30-3/4 inches. Courtesy of Thomas Nygard Gallery, Bozeman, Montana.

|

|

Wiggins’s appeal reaches far. Arlington, Texas art dealer Peter Rainone explains, “Texans love city snow scenes, whether it’s in Paris, New York, or the rare dusting in Dallas. In a Wiggins, collectors find familiar sights—the Plaza, Fifth Avenue, Washington Square Arch—plus all the activity of New York.”

The gregarious painter lived in Dallas in the 1950s, where he painted Dallas and Fort Worth cityscapes and Manhattan scenes, taught, and lectured. When he died in 1962, a large collection of his work was held by the W. R. Fine Gallery in Dallas, before it was turned it over to Rainone Galleries. “In the 1970s, Wiggins sold for between $500 and $2,500,” says Peter Rainone. His level is now in the $10,000 to over $120,000 range for an urban snowfall scene, depending on the size, subject, condition, and quality of the work.

|

Left: Edward Steichen (1879–1973), Snow Bound–Dawn, 1915. Oil on canvasboard, 12 x 16 inches. Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries, N.Y. Right: Walter Ufer (1876–1936) December Morn. Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 inches. Courtesy of Zaplin-Lampert Gallery, Santa Fe, N.M.

|

|

Johannes Berthelsen (1883–1972), who also painted New York blanketed in snow, is described by Dallas art dealer Kayla Roughton of Roughton Galleries as “the next Wiggins” in terms of popularity. Collectors can also find snow scenes by artists not known for the genre such as Walter Ufer (1876–1936), a leading Taos Society artist, Henry F. Farny (1847–1916), who painted the Sioux and Crow in the 1880s, or Edward Steichen (1879–1973), the renowned early twentieth-century photographer.

The record-breaking price twenty-three years ago for Church's 6 by 9 foot finished Icebergs translates to about $345 per square inch. When his 8 by 13 inch oil Study for The Icebergs came up for auction in 2002, the price realized was $465,000,5 which comes out to about $4,500 per square inch—a significant market rise for the snow-and-ice works of one American artist.

|

Art Focus is a regular feature that presents art market trends and collecting themes with related illustrations of works from current museum exhibitions, private collections, and galleries’ inventories.

|

1 Church’s The Icebergs sold at Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, in October 1979 for $2.5 million, at the time the third highest price for a painting at auction after a $5.24 million Velazquez and a $4 million Titian. The Icebergs’ hammer price remained the highest for an American work until 1985, when Rembrandt Peale’s Rubens Peale with a Geranium was bought for $3.7 million by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

2 Recently, the painting was included in the Tate Gallery of London’s traveling exhibition American Sublime. A special exhibition in conjunction with The Icebergs’ reinstallation at the Dallas Museum of Art is on view through January 15, 2003.

3 See John L. Cooley, A.T. Hibbard, N.A., Artist in Two Worlds (Rockport, Mass: Rockport Art Association, 1996).

4 See Maybelle Mann, Walter Launt Palmer, Poetic Reality (Easton, Penn.: Schiffer Publishing, 1984).

5 Study for The Icebergs sold at Phillips, de Pury & Luxembourg in New York on Dec. 3, 2002.

|

|

|

|