|

|

|

|

by Selma and Ray Mead

|

|

|

|

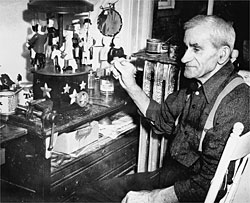

Fig. 1: Anton Zeleznik in his room at the Potter County Home, where he had his most productive period, spanning the decade from 1947 to 1957. Photograph courtesy of Olean Times Herald.

|

High atop a steeply terraced hillside just outside the town of Coudersport, Pennsylvania, sits a simple wooden alpine cross. Tucked under a tree and set some distance from all of the other graves in the St. Eulalia Cemetery, the cross marks the spot where Anton Zeleznik, a Slovenian immigrant, is buried. There is no plaque to mark the site. Occasionally, when the cross has deteriorated and can no longer withstand the region’s harsh winters, it is quietly replaced.

Anton Zeleznik died on June 29, 1957, at 1:30 in the afternoon, in his room at the Potter County Home. He was 81 years old. He had never learned English, was asthmatic, and deaf. Zeleznik’s obituary noted he was a woodcarver, a brief epithet that belies the marvelous legacy this quiet, unassuming man left behind—a series of charming, inventive, often complex works that reflect a sly sense of humor and considerable skill (Fig. 1). They are, in every respect, among the finest examples of the folk art spirit.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: This unique, mechanical yard ornament, with its wooden biplane, rocking tin animals and carved soldier whirligig was made for the Gaberseck family who gave Zeleznik work and a place to stay from the mid-1930s until 1947. Measuring 30" long, it may be one of the most personalized of all his creations. Gaberseck family collection.

|

Zeleznik was born in 1876 in Gorenje Zabukovje, a small village in what is now the Republic of Slovenia. His father was a master cabinetmaker; one of his uncles, a tinsmith.1 At the time of Zeleznik’s birth, the area was part of a volatile region under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy of the Habsburgs. In a ship’s manifest recorded at Ellis Island in 1913, Zeleznik lists his nationality as Austrian, his race as Slovenian. Like many immigrants of the period, he came to America not only to seek his fortune—and perhaps save enough money to send for his family—but also to escape the military service and taxes demanded of him back home.2

Zeleznik’s fortune never materialized. Sponsored by members of the Slovene community in Milwaukee, he made his way to Wisconsin and worked as a laborer in a tannery. While at the tannery, he demonstrated his creative nature by inventing a machine that streamlined production for his fellow laborers. When the machine was patented, however, he received none of the profits nor any of the recognition.3

|

|

(left to right) Fig. 5: One of two pieces Zeleznik gave to the daughter of a part-time bartender at Mitchell’s Tavern who befriended him. The 9"-high figure is missing the swords he would have held in each hand. Private collection. Fig. 6: Perhaps one of Zeleznik’s most elaborate wall-mounted thread holders, this 15-1/2" high x 11" wide piece features a shoe cobbler at its center. Gaberseck family collection. Fig. 4: One of several pieces found in Zeleznik’s room when he died in 1957, this 10-1/2"-high group assemblage features the carver’s characteristic bright colors and whimsical figures. Private collection. Fig. 3: Zeleznik made a number of mechanical cobblers like this 13"-high example. No two are exactly alike; several sport stovepipe hats and sit on rotating platforms. Private collection.

|

Zeleznik’s whereabouts are unaccounted for until the late-1920s, when reports place him among the woodsmen who worked the lumber camps in north central Pennsylvania.4 It was here, working as a blacksmith and farrier in 1932, that he met John Gaberseck and his family, recent immigrants from the Julian Alps region of Western Slovenia. They would eventually become his employers and, to some extent, his “family.”

|

|

|

|

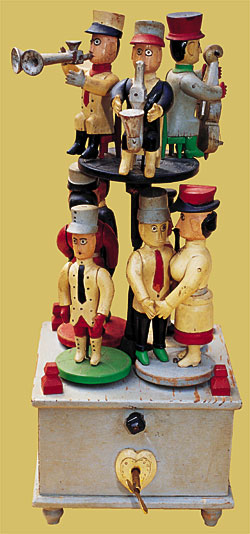

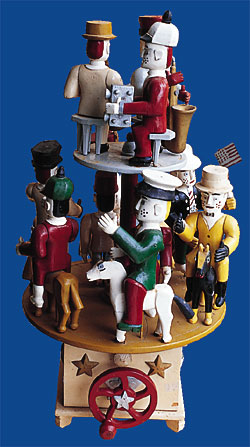

Fig. 9: This is one of two matching 17-1/2"-high mechanical “dance bands” purchased from Zeleznik in 1951 by a Coudersport grandfather as Christmas presents for his two grandsons. Wooden gears inside the base rotate the top tier and each of four platforms on the bottom tier in different directions. Private collection.

|

When the Gabersecks purchased a farm in the Odin Valley of Potter County, Pennsylvania, during the mid-1930s, Zeleznik—along with several other woodcutters who had worked in the then-abandoned lumber camps—went with them. Zeleznik repaired farm equipment and labored as a blacksmith. John Gaberseck, Jr., recalls that “Tony made wagons and wagon wheels with iron rims; he even made his own wood planes5 and tongs. Mostly he was a jack-of-all-trades. But he was a master at what he did.” John’s late brother Joe recalled, “Tony could repair or reproduce any piece of farm equipment needed at that time.”6 In fact, so adept was Zeleznik—he could fix the tiniest item that required the use of a magnifying glass, or the largest, heaviest piece of machinery—that farmers came from considerable distances to pay for his services.

Zeleznik lived with the Gabersecks until 1947. It was during this period that he began to create works of art out of metal and wood. Reflecting the skills he learned as a wagon-maker and blacksmith, Zeleznik’s sculptures reveal his mechanical abilities and ingenuity as well as his wit. Those who remember him report that he was also very private, hiding each creation until it was completed. A perfectionist as well, he was sometimes known to tear a piece apart completely and start over if he felt it wasn’t just right.7

Members of the Gaberseck family and their descendents still own some of Zeleznik’s early pieces. Prized possessions, they are lovingly cared for. Among the treasures are a working clock that once sat in Zeleznik’s blacksmith shed, made from old Model T gears; a carved red, white, and blue cane with a clownish caricature of a man’s head on one end of the handle and a whistle at the other; and an elaborate wood and tin whirligig yard ornament whose various components are powered by the wind.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: One of the earliest examples of Zeleznik’s mechanical “carousels,” this one is also the smallest at just 14-3/8" high. Featuring a whimsical band and a bird that pops in and out of the base when the crank is turned, it was Zeleznik’s gift to a 4-year-old child. Private collection.

|

Created for the Gaberseck family, this whirligig is one of the most personalized of all Zeleznik’s creations (Fig. 2). At its center is a large, wooden biplane with three tin propellers and a tin menagerie, consisting of two fighting roosters and a bucking horse, perched on its fuselage. Set onto one of the wings is a carved cavalry soldier with rotating arms. Two other figures were destroyed by harsh weather. Dressed in the distinctive uniform of the Alpine troops of the Austrian army, the three figures were said to represent John Gaberseck, who rode in the Austrian cavalry during World War I; Jerzy Berlotz, another woodcutter who had served in the mountain troops of the Austrian army;8 and Zeleznik himself. When the wind blew, the witty, delicately balanced assemblage came to life, at times moving so rapidly that it appeared the plane might actually take off.

|

|

|

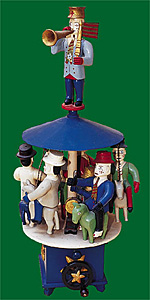

Fig. 7: This rotating carousel, 21-1/2" high, was originally in the collection of Howard and Lucille Schutt, benefactors who recognized the quality of Zeleznik’s work and supplied him with wood and paints during his stay at the Potter County Home. Private collection.

|

In 1947, increasingly debilitated by his asthma, Zeleznik was brought to the Potter County Home in the nearby community of Coudersport. He was 71 years old. Deprived of the company of the other residents because he was deaf and could not speak or understand English, Zeleznik spent much of his time in a small 8 x 10 foot room furnished with a single bed, a chair, and a work table made from boxes.

It was here that Zeleznik’s creativity blossomed and he was at his most artistically productive. Working from morning until night with a penknife, a few small tools, and some paints, his gnarled hands fashioned a charming, brightly colored world that contrasted starkly with his own hardscrabble life. It was a world that recalled the Slovene culture of his native Austria-Hungary, populated by soldiers in full military regalia, busty women in severe Prussian garb, cobblers and blacksmiths, musicians and dancing couples, a child or two, and an array of whimsical horses, dogs, chickens, and birds.

Zeleznik’s carvings were generally mounted on platforms and presented in six different forms. They include:

- individual birds and chickens with wire or wooden legs set into bases, some with movable wings (see article fronticepiece),

- single figures of soldiers, cobblers, blacksmiths or other tradespeople (Fig. 3),

- group assemblages of people and animals or flocks of birds and chickens (Fig. 4),

- whirligig soldiers sporting rifles and wielding enormous swords (Fig. 5),

- wall-mounted thread holders in the form of wooden plaques with a tradesman or bird carved in the center (Fig. 6) and,

- most complex of all, a series of mechanical “carousels” that turn with a crank and sit on wooden boxes housing handmade gears. Often two-tiered, these 17 to 24 inch high constructions might feature a group of musicians and as many as four dancing couples, or a tented merry-go-round with figures on horseback and a single trumpeter perched at the peak of the tent roof (Fig. 7).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10: Toward the end of his life, a grateful Zeleznik offered this combination merry-go-round/dance band to the young doctor who treated him at the Potter County Home. Not wanting to accept such a magnificent gift for free, the doctor paid Zeleznik for it and placed it proudly in his home, where it remains to this day. Private collection.

|

According to Coudersport historian and carver David Castano, Zeleznik’s creations involved devices that “ranged from a simple trip-hammer mechanism that moved a cobbler’s arm as he pounded nails into the heel of a shoe, to elaborate movements that rotated two tiers of figures both in a single direction and, in some cases, on their own axis through a secondary system of gears.”9 The gears, themselves, were either carved completely out of wood, or were created from a flat disc of wood embedded with small nails that were regularly spaced around its circumference.

So painstaking was Zeleznik’s work, that a single wooden figure could be composed of as many as 12 separate parts.10 Elbows were made with precision lap joints, thumbs were pegged into many of the figures’ hands, and each of the pieces was smoothly sanded and then painted with bright enamels. In some instances the torso might be split in half, sanded and reassembled.

To escape his isolation in the Potter County Home, Zeleznik often was seen walking to or from nearby Mitchell’s tavern. There he might pull from his pocket a carved bird or other treasure, which he sold to the bar’s patrons for a pittance or exchanged for a drink. One of the first mechanical carousels Zeleznik made, he gave to the little daughter of a part-time bartender (Fig. 8), who sometimes brought him scraps of wood from the house addition he was building. Two other examples were purchased in 1951 for $9 apiece by a man who wanted matching Christmas gifts for his two grandsons (Fig. 9). During these later years, Zeleznik’s carved figures began to appear larger and more robust, sporting stronger enamel colors, freckles, and tin embellishments; many examples sport tin ears, a gaily striped tin tie or a fanciful tin daisy pin.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 11: Two unfinished pieces—a man (shown) and a woman—were among Zeleznik’s last works. This 8"-high figure, probably carved in 1957, shows the tin ears and tin ties typical of his later pieces.

|

During his stay in the County Home, Zeleznik’s work caught the eye of a number of local residents who were attracted to the style and quality of his carvings. Among them were Howard and Lucille Schutt, who became benefactors of sorts, supplying Zeleznik with wood and paint and purchasing a number of his pieces. They also encouraged others to do the same. An auction of their estate in 1989 may have been the first time those beyond the communities in which Zeleznik had resided, caught a glimpse of his work. A number of his creations were sold to collectors and dealers and have since turned up in the Midwest, New England, and points south, as well as in other parts of Pennsylvania and nearby New York state. The late author and folk art connoisseur Herbert Waide Hemphill, Jr., also had several Zeleznik pieces

in his collection.

In early 1957, old age, asthma, and years of hard labor took their toll. Zeleznik became quite ill and could no longer work at his bench. He was placed in a hospital-type ward at the County Home and treated by a young doctor who made regular visits to the facility. So grateful was Zeleznik for the doctor’s ministrations that he offered the young man a large 24-inch high mechanical merry-go-round as a gift (Fig. 10). The doctor accepted it only upon the condition that he would pay Zeleznik for the beautiful piece. Nearly fifty years later, the cherished memento still sits on the doctor’s mantle at home, carefully protected by a plastic cover.

Zeleznik died in the summer of that year. The few tools he used to create his incredible world were auctioned off, as were his remaining carvings. Two of these pieces—a man and a woman—he never had time to paint (Fig. 11).

|

Selma and Ray Mead of York, Pennsylvania, are collectors of Pennsylvania folk art. Ray is an antiques dealer, and Selma is a freelance writer and editor. They are currently preparing a forthcoming book on Anton Zeleznik. Those interested in contacting the Mead’s with information relating to Zeleznik or his sculptures, may send an e-mail to Selmamead@aol.com.

The authors would like to thank David Peter Castano of Coudersport, Pennsylvania, for sharing his knowledge and research.

|

|

1 Interview with Zeleznik, Olean Times Herald (March 12, 1953)

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 David Peter Castano, first-person interviews with ethnic Slovenes and Croatians, often referred to as “Austrians” in the St. Mary’s area of Elk County

5 A wooden plane is a woodworking tool fitted with an iron blade. Depending on the profile of the blade and plane, they are used either for making shaped moldings or shaving away wood on flat surfaces.

6 Castano first person interview.

7 Ibid, interview with Gaberseck family.

8 Information obtained in Castano’s report, “AIE Grant Project, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, 1987.”

9 Castano AIE report.

10 Ibid.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|