|

|

|

by S. Robert Teitelman

|

|

|

|

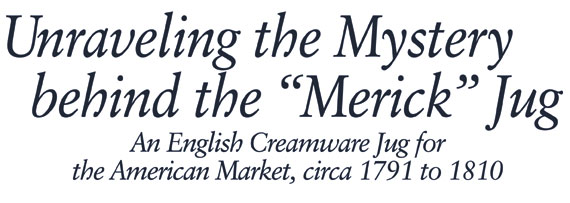

Fig. 1 (left): Baluster-shaped jug, England, 1791–1810. Creamware. H. 10 in. The transfer-printed design displays Columbia, the female personification of America, holding a symbolic liberty pole. Photography by the author. Fig. 2 (center): The names painted under the spout, belong to the persons for whom the jug was made. It is not known whether the jug was commissioned by the Mericks (Myricks) or by a third party who presented it to them. Photography by the author. Fig 3 (right): The hand-painted architectural image is contained within a transfer-printed foliated frame, and is probably intended to represent Dr. Josiah Merick’s (Myrick’s) home and office in Newcastle, Maine. The jug was made between 1791, when the Myricks purchased their property, and 1810, when such blaster-shaped personalized wares made for the American market were going out of fashion. Photography by the author.

|

Although I have been collecting Anglo-American patriotic pottery for more than fifty years, I still become excited over new acquisitions, particularly personalized pieces displaying names of individuals, ships, and organizations. More often than not, the identities of the people or entities those names represent have been lost. Trying to discover the “who, when, and where” is like solving a mystery. For me, the necessary research is a joy not a chore. It links me to an object, its original owners, and to their lives and the era in which they lived. At times I have been frustrated and forced to accept that some puzzles have missing pieces that may never be found. However, by exercising patience and perseverance I have had a success rate that keeps me encouraged.

Personalized baluster-shaped creamware jugs like the one that belonged to Josiah and Mary Merick, whose names appear along with American historical designs, were popular from 1790 to 1810. New England and mid-Atlantic seafarers, whose vessels called at the port of Liverpool, England, were attracted to the patriotic wares designed specifically for the American market by enterprising British potters in Liverpool and Staffordshire. It was fashionable, especially for sea captains, to commission jugs, bowls, mugs, or plates inscribed with their name or initials, or those of a family member, sweetheart or friend, their ship, business affiliation or Masonic lodge. Decoration usually combined several designs chosen from motifs relating to American national emblems, patriots, presidents, heroes, military and naval engagements, liberty, justice, peace, plenty, and independence, masonry, industry and trade. An example of the latter is “May Commerce Flourish” (Fig. 1) a printed design that appears on the reverse side of the Merick jug. Columbia, the female personification of America, is seen holding a pole topped with a conical cap symbolic of liberty. In her right hand she holds a shield bearing the arms of the United States, indicating that the piece was made for that American market.

|

|

|

|

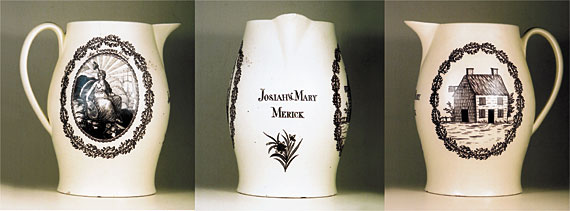

Fig 4: Detail from a photocopy of a manuscript map of Newcastle, Maine, drawn about 1805, showing “Dr. Myrick(‘s) house.” The front of the house faces south. The side or street entrance to the doctor’s office, faces west. Whereabouts of original map unknown.

|

When I purchased this jug from dealer William Kurau, there was no available information about its provenance. My research project began with seeking answers to the obvious questions of who Josiah and Mary Merick were (Fig. 2); when and where they lived, and what their relationship, if any, was to the building depicted on their creamware jug (Fig. 3)? The following is an account of how I went about searching for the answers. It was an experience that culminated with a delightful and rewarding adventure.

Because these wares were principally brought into and used in New England and the mid-Atlantic states, I first examined the federal census records for those states, starting with 1790—the year of the nation’s first census—and continuing through 1800, 1810, and 1820.1

My search included several variations in spelling: Merick, Merrick, Mirick, and Mirrick. In the 1790 census records. I found three Josiah Merricks (spelled with two “r”s), one living in Hampstead Township, New Hampshire, another in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the third in New Haven, Connecticut. As only the head of the household’s name is given in census records, in order to find the name of a spouse it was necessary to turn to other sources such as official state and church vital records, local histories, and family genealogies. Exhaustive research revealed that none of these men was the owner of the creamware jug.

|

What I consider the key to the “Merick” mystery came during my research at the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston, Massachusetts. There I discovered the Genealogy of the Merrick-Mirick-Myrick Family of Massachusetts 1636–1902.2 The Myrick variation of the spelling had not occurred to me. Excitedly I turned to the index and found listed a Josiah and Mary Myrick, of Newcastle, Maine. Could this be my answer? There was only a difference of one letter, a “y” instead of an “e.” Misspellings are common on these wares. For example, I have a bowl and jug ensemble; each displays a similar hand-painted ship’s portrait inscribed The Patterson, and beneath it, the name of the captain “Jonathan Aborn” correctly spelled on the bowl, but erroneously spelled “Abron” on the jug.

Within the time and geographic framework, I discovered no other husband and wife combination of Josiah and Mary Merick, even with a variation of that spelling. I therefore believe that my “Josiah & Mary Merick” were in reality the Josiah and Mary Myrick of Newcastle, Maine.

I learned from the Merrick-Mirick-Myrick genealogy and from a local history of Newcastle that Josiah Myrick was a doctor, born in Eastham, Massachusetts, on September 20, 1768; that he married Mary Clark of Brewster, Massachusetts, on September 24, 1789; and that in 1791 they settled along the coast in Newcastle, Lincoln County, Maine, about a quarter of a mile from the Damariscotta Bridge.3 Dr. Myrick practiced medicine for over forty years and was a leading member of the community. He died at the age of 60 on April 9, 1828. Mary died at the age of 84 on September 9, 1849. Both were buried in the Pine Knoll Cemetery in Newcastle.

My next step was to learn whether the Myricks rented or owned property in Newcastle. If they were landholders, did their house survive, and did it match the image on the pitcher? I asked a friend, Bob Naylor, now retired and residing in Owlshead, Maine, if he could conduct a deed search at the Lincoln County Court House in Wiscasset, Maine. He undertook the task and found a deed from Thurston Witing, grantor, to Josiah Myrick, grantee, dated November 22, 1791, conveying 26H acres “on a gully that leads into the Damariscotta River at the eddy, so called.”4 This confirmed my findings in the genealogy.

|

|

|

|

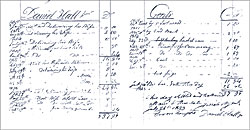

Fig. 5: Pages 108 and 109 of Dr. Myrick’s ledger of 1805 to 1825. Of interest is the cost of delivery of a baby (page 108) and the payments by barter of cider, corn, and labor received for services (page 109). Courtesy of the Lincoln County (Maine) Historical Association.

|

Did the house painted on my jug stand on that parcel of land? In all probability, Dr. Myrick had his office and home in one structure. The two entrances depicted on the jug could refer to a main entrance for the dwelling and a side entrance for his office and/or apothecary shop, a rather common arrangement for the time. Over the side door hangs a sign painted with three bird-like images that may have significance, but may also reflect the whim of the English decorator who was made aware that there was a sign but was not given details. The thatch roof and diamond pane windows are indicative of a seventeenth or early-eighteenth-century New England house. They may have been on an existing structure into which the Myrick’s moved, or they too could be in part or totally whimsical.

Last summer I was a house guest of the Naylors, and Bob indulged me in an expedition to locate the Myrick property in Newcastle, some twenty miles south of Owlshead. We knew that the property was a quarter of a mile from the Damariscotta bridge. After crossing it, we explored northwardly, and reaching the presumed spot, we saw no building that resembled the image on my jug. However, just beyond the entrance to a nearby large estate was what appeared to be a late-eighteenth- or nineteenth-century frame house. I wondered if it was the original Myrick structure that had been altered, and so we decided to inquire.

|

The tenant occupant was unaware of any history on the house, and directed us to the owner, Mrs. Josephine Hart, who lived in the main house on the estate. Fortunately Mrs. Hart was at home. Though fascinated by my mission and a longtime resident of Newcastle, she had never heard the name of Myrick. She suggested that Timothy Dinsmore, an archaeologist in town, might be able to help. A telephone call was placed to him. He was aware of Dr. Myrick, but said his father, Carroll Dinsmore, who lived very close to the former Myrick property was much more knowledgeable.

The senior Mr. Dinsmore invited me to visit. He greeted me with a photograph of a manuscript map dated 18055 (Fig. 4) showing the location of Dr. Myrick’s house on his 26H acres, which, as described in his deed, extended to the “gully that leads into the Damariscotta River.” Mr. Dinsmore pointed out where the house had once stood; it was no more than one hundred yards from his own home on what is presently known as Hillcrest Road near Academy Street. He believed that the building was demolished when the Maine Central Railroad acquired a right of way through the property in the 1870s. He mentioned that one of Dr. Myrick’s ledgers had come up for sale about five years ago, and had been purchased by Jane Tucker of Wiscasset, Maine, and given to the Lincoln County Historical Association in Wiscasset. Mr. Dinsmore also informed me that George F. Dow of the Nobleboro (Maine) Historical Society had written an article about the ledger in the Lincoln County News.6 (Mr. Dow subsequently sent me a copy of the article and his genealogical notes on several generations of the Myrick’s, beginning with Josiah and Mary.)

|

I was under a time constraint, but Bob drove me to the Lincoln County Historical Association in Wiscasset to quickly examine Dr. Myrick’s ledger, which he’d kept from 1805 to 1825. It contains the names of his patients, the dates of visits, the treatment, charge for services and/or medication, and the patients’ method of payment. In many cases the doctor was paid by barter, with cords of wood, animals, produce, a day’s labor (Figs. 5). No reference was found to the jug, but time did not allow for a comprehensive search. Reading through the accounts, ledgers, journals, and other primary source materials that once belonged to the original owner of an object, however, gives insight into the character, personality, and business relationships of that person. Such awareness increases the appreciation of the object, and an understanding of its possible role in the original owner’s life.

About the circumstances under which the Myricks acquired their jug, I have no knowledge, nor may I ever. However, I suspect that it was presented to the Myricks by a grateful patient, either a Newcastle sea captain, or a patient who arranged with a seafaring middleman to commission it in England. The jug seems too extra- vagant as payment for services—though a thorough examination of the accounts might reveal otherwise—and is more likely a presentation piece. It is also possible that the Myrick’s ordered the jug themselves, perhaps in celebration of their new home and office; the timing is certainly appropriate for they acquired their property when such jugs were popular.

My immediate questions have been reasonably answered, but I shall continue my research on future trips to Maine. Though not conclusive, this story illustrates the many avenues one often needs to pursue, and in this case, the journey will continue. Through my endeavors, my appreciation of the Merick/Myrick jug has been greatly enhanced.

To the collector who has a personalized piece with an unidentified provenance, I urge you to undertake similar research. It may unravel a mystery that will give your piece back its soul.

|

Acknowledgments

I am especially grateful to my friend Robert E. Naylor who found the original deed to Dr. Myrick’s Newcastle property and who shared the delight of my Newcastle/Wiscasset adventure. I am indebted to Josephine Hart for her introductions to Timothy and Carroll Dinsmore, who made it possible for me to pinpoint the Myrick property. I also wish to express appreciation to Peggy Sheils, Director of the Lincoln County Historical Association, Wiscasset, for granting the publication rights to reproduce two representative pages from Dr. Myrick’s ledger.

|

S. Robert Teitelman is a retired attorney, avid collector, lecturer, author of articles on Anglo-American patriotic pottery of the Federal period, and books on eighteenth-century Philadelphia views.

|

|

1 Census records are generally available at our largest public libraries, historical and genealogical societies, also at the National Archives Regional Offices.

2 George Byron Merrick (Madison, Wis.: Tracy Gibbs & Company, 1902), 407.

3 Five children were born of their marriage, one of whom was a physician, another a shipbuilder and prosperous businessman.

4 Recorded February 7, 1792, in the Lincoln County Court House, Wiscasset, Maine, in Deed Book 28, p. 34. The purchase price was forty pounds, equivalent at the time in dollars to about $133.00. For a comparison, a man’s labor with a “pair of oxen” was then worth $1.67 a day.

5 Present whereabouts of the original manuscript map is unknown. Typed in the lower left corner of the photographic reproduction is the following, “This plan was drawn by Ira Chamberlain when about 93 years old, it represents the village as he remembered it in the spring of 1805 when he resided here. This is a copy of Mr. Chamberlin’s plan made in February 1894 by Alanzo Glidden. This is a photographic copy made July 4th by D.J. Lindsay.”

6 George Dow, “Dr. Josiah Myrick and his Patients” in Lincoln County News, Newcastle, Maine (May 23, 1996).

|

|

|

|