|

|

|

The art scene lights up with impressions of dark from

Whistler's Nocturnes to Boston Japanning

|

|

|

|

|

|

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Blue and Silver: Screen, with Old Battersea Bridge, 1871–1872. Distemper and gold paint on brown paper laid on canvas stretched on back of silk; 195.0 x 182.0 cm. © Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow.

|

During his famous 1878 libel suit brought against English critic John Ruskin, the question was posed to James A. McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), one of America’s most influential artistic exports to Europe, “What is your definition of a Nocturne?”

Whistler defined his newly applied term for night scenes as “an arrangement of line, form, and color first…and I have chosen the word Nocturne because it generalizes and simplifies the whole set of them.”

His subtle works, odious examples of non-art according to Ruskin, presented a vision of night that varied radically from the detailed, misty evening dock scenes of his contemporary John Grimshaw (1836–1897) and the lively Parisian street scenes by later “night” artists such as Edouard Cortes (1882–1969). Whistler saw chimneys silhouetted in the evening mist along the Thames as “campanili – and the warehouses, palaces in the night,” a modern aesthetic theory that had a profound impact on artists such as Aaron Harry Gorson (1872–1933).

|

|

|

|

James A. McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903), Nocturne, Palaces, 1879–1880. Etching and drypoint. Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Rosenwald Collection. Photo courtesy of Corcoran Gallery of Art.

|

Contemporary Victorian artistic taste leaned toward academic tradition, precise detail, and elaborate finish. So Ruskin wasn’t alone in his criticisms. Whistler claimed £1,000 in damages from Ruskin. The judge awarded him a farthing (one quarter of a penny) and trial costs helped plunge Whistler into debt.

The Fine Art Society financed Whistler’s Venetian trip in 1879 to help the artist recover his losses. The resulting work included his most celebrated Nocturne etchings, each plate superbly rendered in varied lines of black against cream.

It was Whistler’s patron, Liverpool shipowner F. R. Leyland, who came up with the series title Nocturnes. (Whistler decorated Leyland’s London dining room, The Peacock Room in 1876–1877, now reconstructed in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) These atmospheric works were painted from memory as prescribed by the French art theorist Lecoq de Boisbaudran. In contrast to the plein-air painting of the then emerging impressionist movement, Whistler made quick notes at the scene then finished the work indoors. He mixed his paint with copal, mastic, and turpentine to increase fluidity. The liquid nature of his formula made lightening and darkening tones easier as he worked.

To achieve a blue-toned Nocturne, the artist prepped the canvas with a red ground, or he began with a mahogany panel. The dark red body color came through and contrasted with the wide sketchy strokes of blue pigment laid over it. To avoid a purple tone, Whistler layered semi-translucent grays. Rarely was a white ground used, more often a warm black or gray served as the background, but Whistler consistently experimented.

|

|

|

John Atkinson Grimshaw (English, 1836–1897), Calm after the Rain. Courtesy of Richard Green, London.

|

|

|

|

Edouard-Leon Cortes (French, 1882–1969), Boulevard de la Madeleine, Soir de Neige. Oil on canvas, 19-1/2 x 25-3/4 inches. Courtesy of Roughton Galleries, Dallas, Texas.

|

Dark Scenes

Whistler’s Nocturnes series embraced a wide range of tonalities from soft gray to jet black, but the richer colors were more in keeping with contemporary taste. One of the dark jewel tones favored by Victorians in the mid-to late nineteenth century was a pigment with the intriguing name “mummy brown.” Deeper than burnt umber, this unstable color was in common use from the colonial period, but especially appealed to artists in the romantic era for its sublime and frightening connotations. Adeline’s Art Dictionary (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1891) defined it as “a rich brown pigment, which is composed of white pitch, myrrh, and the flesh taken from ancient mummies. But whether genuine or not, it cannot be recommended to the painter, as although it is a rich color, it dries with difficulty, is not permanent, and may contain ammonia and particles of fat.”

|

|

|

John J. Enneking (American, 1841–1916), On the Corregio, 1876. Oil on canvas, 20 x 26 inches. Courtesy of The Boston Art Club, Boston, Mass.

|

Rich jewel-toned pigments were employed by the Boston-based artist John J. Enneking (1841–1916), who was known as “The New England Sunset Painter.” He was one of only a few artists to paint evening scenes between 1874 and 1890, a time when sunny plein air work began to dominate landscape painting.

“Not many people realize that Enneking was the first American painter to come back to the U.S. from France as a full impressionist in 1874. He painted alongside Monet, Pissarro, and Degas in Giverny,” notes Patricia Jobe Pierce, who is preparing the Enneking catalogue raisonné and is the author of John Joseph Enneking, American Impressionist Painter (1972).

|

|

|

|

Aaron Harry Gorson (American, 1872– 1933), Nocturne, Steel Mills, Pittsburgh. Oil on canvas, 36-1/4 x 41-1/4 inches. Courtesy of Spanierman Gallery, LLC, New York City.

|

Like Whistler, Enneking was experimental and his post-Giverny works are difficult to categorize. While his technique followed the impressionist’s quick brushwork and use of heavy impasto, his palette was darker and influenced by the French Barbizon and Munich School. “His pigments intermingle, weave, dash, and swish,” says Pierce.

Prior to Enneking, Boston artists already had an established tradition of night scenes and dark palettes. Romantic-era thinking, popularized through literature, was certainly an influence for area artists such as Washington Allston (1779–1843) and other American painters from Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847–1917) to Ralph Blakelock (1847–1919). Incidentally, the bleak verse of Boston-born poet Edgar Allen Poe (1809–1849) was a favorite of Whistler’s.

|

We stand upon the brink of a precipice.

We peer into the abyss. We grow sick

and dizzy. Our first impulse is to

shrink from danger, and yet,

unaccountably, we remain.

—Poe, The Imp of the Perverse

|

|

|

|

Ralph Blakelock (American, 1847–1919), Afterglow. Oil on canvas, 16 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Vose Galleries, Boston, Mass.

|

Whistler was born just north of Boston in the city of Lowell, Massachusetts. But he never returned home after he left for Europe in 1855 at the age of 21. (Whistler’s mother lived with him in London at the time of her famous sitting). Had he stayed in the Boston area, he might have crossed paths with the influential artist William Morris Hunt (1824–1879), who, like Whistler, was known for his controversial lectures on art, as well as his Barbizon-inspired work, including twilight landscapes.

Two decades earlier, Allston, a Harvard graduate, was hailed as the nation’s leading artist for his romanticized allegorical landscapes. A friend of Washington Irving, author of the dark classic Legend of Sleepy Hollow, Allston was so highly revered for his poetical scenes, especially his blackish, moonlit landscapes, that a section of Boston across the Charles River from Harvard was named after him.

|

|

|

|

Chinese lacquer box. Courtesy of Sallea Antiques, New Canaan, Conn.

|

Dark Surfaces

Boston saw another, earlier period when the color black was favored in the decorative arts. Colonial artisans, with a significant concentration identified in Boston, were inspired by John Stalker and George Parker’s Treatise of Japanning and Varnishing (Oxford, England, 1688), which provided an explanation of how to imitate oriental lacquer. As a luxury item exported from China and Japan to Western markets during the China trade era between the 1580s and 1880s, lacquer ware was expensive and in high demand.

Made from the sap of the Asian lac tree, lacquer is purified and then applied to a wooden surface where it hardens to a glossy, midnight finish. To create a similar appearance, but at a lesser cost and using a more accessible process, ornamenters in the English furniture trade began in the 1680s to paint “japanned” surfaces in solid colors of black, dark green, and red (often with a blue or blue-green underpaint), which were overlaid with fanciful decorations including pagodas, animals, flora, and fauna.

|

Their eighteenth-century counterparts in Boston created their own distinct lacquer simulation by underpainting with a red-brown color (sometimes called venetian red). When the surface dried, paint made with lamp black was dashed on so that some of the red would show through to imitate the look of tortoiseshell. Figural designs were applied with gesso (chalk mixed with glue), on top of which silver or gold leaf was added. Layers of golden-toned varnish created a lustrous finish akin to true lacquer.

|

|

|

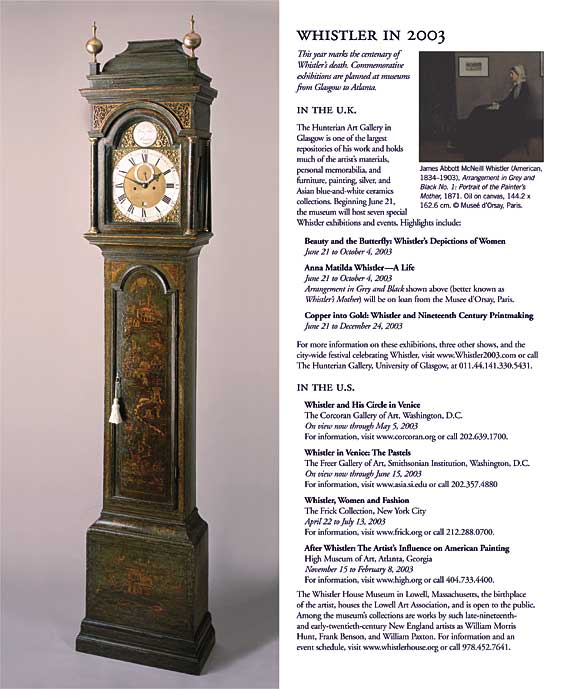

George II period green japanned longcase clock, ca. 1740–1745. H. 8' 5". Courtesy of Charles Edwin, Inc., Louisa, Virginia. Jill Probst of Charles Edwin, Inc., describes the decoration as “an English artist’s idea of how a Chinese artist would portray Constantinople during the Crusades.” The case surface appeared black until a cleaning revealed the original green japanning.

|

|

|

|

Pair of French classical urns with a patinated finish, ca. 1825. Courtesy of Charles & Rebekah Clark, Woodbury, Conn.

|

When dealers Jill and Charles Probst of Charles Edwin, Inc., discovered a George II black japanned longcase clock, they had it carefully cleaned to preserve the extraordinary decoration of European sailing vessels and Middle Eastern motifs. The cleaning revealed something more about the decoration: The circa 1740 piece was originally green japanned, but had appeared black after centuries of dirt accumulations were trapped under varnish applications.

While sometimes a black surface—achieved through time and wear—is not intended, there are plenty of processes to create a rich-looking finish. Pieces can be patinated, ebonized, painted, lacquered, and japanned, or dark materials like basalt, gouache, bronze, onyx, charcoal—and mummy brown—used.

Lacquer ware appears in several of Whistler’s works such as Variations in Flesh Color and Green: The Balcony (Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.). An avid collector of Asian art and objects, Whistler also admired Chinese blue-and-white porcelain and the decorative aesthetic of Japanese prints which proved so influential to his oeuvre. Whistler’s London dealer, The Fine Art Society, shared these tastes and sold prints by Hokusai and by Hiroshige, who was known for dark, moonlit temple scenes.

|

|

|

Art Focus is a regular feature that presents art market trends and collecting themes with related illustrations of works from current museum exhibitions, private collections, and galleries’ inventories.

|

|

|

|