Bordeaux, Boats & Botero

- William Koch’s coastal Massachusetts home contains a ship room modeled after the captain’s quarters of an 1812 frigate. The room holds a writing desk that belonged to a surgeon aboard the U.S.S. Constitution. The replica trophy from Koch’s 1992 win of the America’s Cup, one of an extensive collection of sailing trophies (not shown), is juxtaposed with British paintings depicting the 1812 defeat of the American ship Chesapeake by the H.M.S. Shannon. Maritime antiques such as a circa-1790 carved prisoner-of-war ship’s model (made by a French sailor during the Napoleonic Wars) and an early 19th century Anglo-Indian carved teakwood ship’s bench on the far wall, along with teak and holly flooring, enhance the nautical theme. The circa 1825 figurehead retains much of its original paint. George III yew wood Windsor armchairs are arranged around a 19th century English pine and oak tilt-top table set for a wine tasting. An adjacent computerized wine cellar provides Koch with easy access to his renowned 35,000 bottle collection.

The roll call is impressive: Degas, Modigliani, Rodin. This personal collection encompasses impressionist and postimpressionist masterpieces, western paintings and sculpture, antiquities, maritime art and antiques, and, most recently, Native American objects. There are examples of artists’ signature works—Fitz Hugh Lane’s luminous The Golden Rule, Picasso’s Night Club Singer, and one of Monet’s Water Lilies series, to name a few. During the summer months, these works of art reside at Homeport, the seaside Cape Cod, Massachusetts retreat of William I. Koch, an entrepreneur and first class sailor, wine connoisseur, and art collector.

Naval scenes from the War of 1812—specifically the action of the U.S.S. Chesapeake versus H.M.S Shannon—are the current focus of this insatiable collector, whose artwork, in part, migrates with him from Palm Beach to the Cape each summer. So far, Koch (pronounced “coke”) owns seven depictions of the battle where his ancestor, Captain Jacob Lawrence, mortally wounded, uttered the words that became the U.S. Navy motto: “Don’t give up the ship!”

Painted chronicles of this American defeat hang in a coffered-ceiling ship room that Koch had fashioned after the captain’s quarters of various ships such as the U.S.S. Constitution, famously known as the unsinkable “Old Ironsides,” on which Lawrence had once held a position.

Situated on the shores of Nantucket Sound, the subterranean ship room at Homeport also holds a selection of important maritime antiques. One highlight is a Chinese export day bed (ex-Winterthur collection) that belonged to Nicholas Brown, founder of Brown University and one of America’s great early merchant captains. “I look for art and objects that have meaning to me and relate to my interests,” explains Koch, a skipper himself who overcame 100 to 1 odds to win the America’s Cup in 1992.

|

- On the front lawn, a family of Botero sculptures welcomes visitors to Homeport. The 1929 cottage, which Koch purchased in 1983, has undergone several renovations and additions, each carefully supervised by the collector, resulting in a capacious setting for art and family replete with sun-filled rooms and ocean views.

As the enterprising founder of an alternative energy and technology company, the West Palm Beach-based Oxbow Corporation, and a chemical engineer with three degrees from MIT, Koch’s approach to his interests is analytical as much as it is emotional. “The America’s Cup is a siren that lures you in and can consume you,” Koch says with a grin. Expert team management, intense dedication, and a high-tech boat design developed by MIT scientists contributed to his achievement in 1992. Koch takes a similarly passionate approach to his art collecting.

Beginning to purchase art seriously in the early 1980s, Koch teamed up with John Walsh, formerly director of the Getty Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for guidance in the initial formation of the collection. These days Koch solely selects and installs his blue chip art. He follows the market by reading trade publications and auction catalogues, frequents international galleries and shows, and keeps in contact with experts in the field.

“Bill is a very knowledgeable collector,” says maritime art and antiques specialist Alan Granby of Hyland Granby Antiques in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. “He has the ability to assemble superior collections of everything from figureheads to wine.” (In 1996, Wine Spectator named Koch’s cellar, which contains such rarities as Thomas Jefferson-signed bottles of French vintages, the best private collection in the United States.)

- Over the Delft-tiled living room fireplace Koch prominently features Modigliani’s 1917 Reclining Nude. On each side are works by Degas, Homer, and de Nittis. When the 1901 Blue Period Picasso titled Night Club Singer (on the far right) recently was rematted, a previously unknown and very irreverent scene depicting the young artist’s first dealer, P. Manach, was revealed on the reverse. On the right is the golden-colored Mythical Figure by Dadaist Jean Arp. Mid-19th-to early-20th century bronzes include works by Degas, Lehmbruck, and MacMonnies. The 19th-century brass mounted writing desks serve as end tables.

The Homeport living room displays stellar American and French paintings and sculpture of the nineteenth to late twentieth centuries by luminaries from Winslow Homer to Marc Chagall. Buttersworth marine paintings grace the entryway. Punctuating the white walls of

an upstairs hallway is a suite of important American paintings that includes The Brook: Medfield from the 1889 series by Dennis Miller Bunker, one of America’s earliest impressionists.

Koch annually chooses artwork from his 400-strong collection to transport from his 40,000 square foot primary residence in Florida to the Cape Cod beach house. At a third of the size, the summer home accommodates only a careful selection. Thus, favorites such as enormous Fernando Botero sculptures, Alfred Stevens’s engaging The Coquette, and much of the maritime collection (excluding over 120 boat models of every defender and challenger in the America’s Cup), travel north while the majority of Koch’s trove stays behind. (The collection has grown so large that Koch admits to now hanging art on the ceiling of the Palm Beach home. “It works well with Native American textiles,” he says.)

Even while the Cape home showcases exquisite French Impressionist oils and other masterpieces, its primary function is as a family getaway. Homeport offers Koch an unbuttoned atmosphere he can share with his four children, ages 3 to 16, and his fiancée, Bridget Rooney and her 6-year-old son, Liam.

The relaxed ambience of the interior spaces, designed by Koch himself, befits life by the sea. His museum quality art is arranged with a livable mix of contemporary furnishings, English and American antiques, and colorful oriental rugs that are friendly to sandy feet. In the living room Jean Arp’s 1950 sculpture Mythical Figure, with arms outstretched in the manner of an early Cycladic figure, is placed on the floor at eye level to Koch’s youngest daughter, Robin, who is known to hug the piece because it reminds her of “E.T.”

|

|

- Signature paintings by Frederic Remington lend a western frontier theme to the dining room. The circa-1905 works are (left to right) An Argument with the Town Marshal, Evening on a Canadian Lake, and Coming to Call. All three works were recently loaned to the exhibition Frederic Remington: The Color of Night at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. To date, several exhibitions of selections from the Koch collection have been mounted including three with accompanying illustrated catalogues: one in his hometown at the Wichita Art Museum in 1996 and the others at the Yellowstone Art Museum, Billings, Montana, in 2000 and 2001.

“My kids are my main passion,” says Koch. Besides a flotilla of boats docked a stone’s throw from the house, the children enjoy a playscape on property across the street named Wyatt’s World after Koch’s oldest son, which is open to neighborhood kids. (Koch also gives local children access to his art collection in Palm Beach where middle and high school students regularly come by to study. “The kids give you a whole new perspective on the artwork,” he says.)

Born and raised in Kansas, some of Koch’s interests stem from his childhood in the heartland. Fields of tall grass waving in the wind sent him imagining waves of a different kind. He got his first taste of sailing at a camp on an Indiana lake, but took to the sea only eight years before his daring America’s Cup triumph. “I became so intense that friends wouldn’t cruise with me,” he admits. “That’s why I started racing.”

His passion for art developed along similar lines, germinating with a brief introduction acquired through his parents that later grew into a serious pursuit. His father, who was founder of Wichita-based Koch Industries, the second largest privately owned company in America, and his mother, an artist, formed a small collection—a few Renoirs and Bentons, a Gainsborough, and several Orientalist paintings.

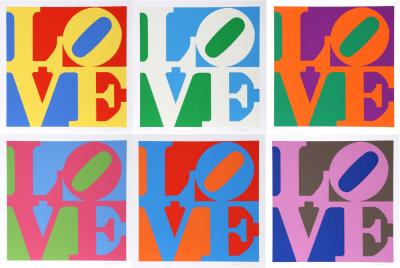

Aside from personal and historical significance, Koch pursues works that speak to his emotions. The bulbous animal and figural sculptures of contemporary Columbian artist Fernando Botero draw him in with their expressive friendliness.

A surreal Magritte purchased at the 2003 Palm Beach International Art & Antique Fair struck him as peaceful and dreamlike. “I like to have fun with paintings,” Koch concedes about his taste for works representing divergent movements, cultures, and periods. “I’m sure an art historian would have a fit over how I mix them.”