|

| Home | Articles | A Fancy for Color and Design: A Collection of Pennsylvania Folk Art |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peaceable Kingdom, by Edward Hicks (1780–1849), showing Penn’s treaty with the Indians in the background and dated 1837, was intended to promote the Quaker belief in peaceful coexistence as inspired by the biblical prophecy of Isaiah. This iconic image is one of two by Hicks in the collection. The other, The Residence of David Twining, is of the home where Hicks spent much of his youth as a foster child.

The Lancaster County blanket chest is identified with the name and date Mariaa Bachmen/DEN:8:IENNER in Anno: 1784 (8 January 1784) in sulfur inlay, a process where molten sulfur is poured into incised areas and scraped and polished smooth. A chip-carved polychrome floral basket attributed to Wilhelm Schimmel (1817–1890) of Cumberland County, is a rare alternative to his more familiar eagles. |

Objects are identified with the region in which they were made. They reflect the cultural traditions and training of resident craftsmen and the aesthetic preferences of patrons. Among the most recognizable group of regional furnishings are those associated with the Pennsylvania Germans of the eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries. Their blanket chests, boxes, whimsical carvings, toleware, frakturs, and numerous other decorative and utilitarian goods were often colorfully embellished with fanciful hearts, tulips, and exotic and realistic animals—motifs grounded in the rich cultural heritage of Europe, from which these largely agrarian peoples came.

Demand for Pennsylvania German folk art has risen significantly over the last few decades. While many collectors have only recently begun to pursue these visually dynamic and charming objects, one couple has been acquiring them for over fifty years, and today has one of the most significant collections in private hands. Ironically, they did not start out with the idea of being collectors, but began purchasing this regional folk art because they needed to furnish their home and found it appealing.

“When we were first married,” the wife explains, “we knew nothing about antiques. Our first home was a wonderful old farmhouse that I planned to renovate and update to incorporate our Nakashima and Danish Modern furniture. Two friends who had just graduated from the first Winterthur program convinced me to visit Mr. du Pont and see his museum before I did anything. That experience,” she says, “along with living in the old house itself, changed my life, and from that point on I was hooked.”

The couple says that folk art appealed to them because “we had dogs and young children, and didn’t want a museum.” The wife points out, “We still use everything. We walk on the hooked rugs rather than hang them on the walls, use the stoneware, and have sturdy regional furniture that will probably hold up longer than the ’50s furniture we had originally purchased.” The husband and wife also find Pennsylvania German folk art alluring in the contemporary feel of its design, particularly in the watercolor, pen, and ink frakturs, which are a significant component of this collection and among the first items the couple acquired. Written in calligraphy and illuminated with decorative motifs, frakturs had an important role in Pennsylvania German society. Among other things, hey recorded events in people's lives

|

such as births and baptisms; were expressions of devotion to God; and they served as writing samples, gifts, or rewards of merit. The term itself refers to the broken "fractured" lettering of the text, and today is generically associated with all Pennsylvania German watecolors. Makers of fraktur were schoolmasters and itinerant scriveners who favored elements such as birds, hearts, angels, and flowers, which served either as religious symbolism or were purely intended to delight the eye. Motifs such as the distelfink (a thistle finch) originated in Europe, but American imagery, including the Carolina parakeet and bald eagle, was incorporated into the designs. Popular between about 1750 and 1850, the most elaborate and fanciful examples date from about 1790-1830.

"In my estimation," notes the wife, "Frakturs are the poor man's Paul Klee. I buy them for aesthetic appeal and for their whimsical character." The decorative motifs found in these frakturs are in fact the thread that connects many of the objects in the house. "Now it has become an obsession to acquire examples of different hands and townships that we do not have," she adds.

In addition to the frakturs, the couple has developed several other categories in their collection: painted furniture, chairs from the Savery school of Philadelphia, hooked rugs, textiles, sculptural canes, redware, painting, and whimsical carved, cast or painted snakes. "This has not been intentional," says the wife. "We just gravitate towards these areas and have been consistent over the years.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Centered above the rare ca. 1710–1730 Chester County wainscot armchair, which has an enclosed paneled base and retains its original paint, are three frakturs. The elaborate center fraktur, made by G. Seiler (working 1794–1808), Dauphin County, 1793, is a recent purchase. Above and below it are images by John Conrad Gilbert (1734–1812), Reading and Berks County. Born in Germany, Gilbert served in the Revolutionary War and later became a schoolmaster. His fanciful figures are recognizable for their pronounced underbites. |

|

And while their focus is on material from Pennsylvania, they also own a number of objects from New England. The unifying factor is successful design. In addition, the wife points out, “All the objects need to have strong color and patina and be in good condition.”

Their love of dynamic lines and color is evident in the many blanket chests found throughout their home. Having numerous examples, however, can prove a challenge. As the wife says with resignation, “Though I am an interior designer, the collector in me sometimes fights the decorator in me. This is most apparent in my office, where my closet door is partially blocked by a Berks County unicorn chest—there is nowhere else to put it!”

Though the unicorn chest will likely stay, there is a continual culling, conserving, and reassessing of the collection, with most forms having been upgraded two or three times. “We are fortunate to have the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Winterthur nearby,” says the wife.“I often go prior to an auction or antiques show to refresh my memory on what has aesthetically stood the test of time. That’s the role of museums—to educate people.” Her husband adds, “My wife also has a great eye and as a result we have been kept from making too many mistakes along the way. We have always tried to buy the best we could afford. Early on that wasn’t much and for a while the house was a little bare.”

“Collecting,” notes the wife, “has greatly enriched our lives. It’s fun—we’ve traveled to interesting places and have met some outstanding people.” “We are always learning,” adds her husband. “I have worked in the technical side of business for years, and it has always been a pleasure to come home to a totally different environment, to a house that is decorated with fun and whimsy.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(right) A spreadwing sternboard eagle by John Haley Bellamy (1836–1914) of Kittery Point, ME., presides over the many frakturs in this room, including Solomon’s Temple (over the slat-back chair) from the Schwenkfelder community, Montgomery County. Another fraktur from this group is seen far lower left and is characteristic of the richly colored, dense, foliated frakturs associated with David Kriebel (1787–1848). Between the two is a wonderfully imaginative fraktur with clock and little faces by Samuel Bentz (1792–1850), the “Mount Pleasant Artist,” Lancaster County, 1811. The Windsor low-back bench, ca. 1770–1803, with carved knuckle arms and energetic turned legs is attributed to Ebenezer Tracy Sr. (1744–1803), Lisbon, CT.

In the hallway beyond is Mother and Child, ca. 1835, from upstate N.Y.; it is unusual in its gold leaf details (illustrated in Brant and Cullman, Small Folk [1970] 26). The Berks County blanket chest is of the lift-top form preferred within the Pennsylvania German community. The painted architectural arrangement is a common treatment and is an alternative to applied panels. The name of the original owner, Elizabeth Neu, and in 1797, are painted on the front. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(left) With the lack of closets in eighteenth-century Pennsylvania German houses, case furniture such as this elaborate painted schrank, ca. 1790, served a useful purpose. This example has recently been attributed to the shop of joiner and decorative painter John Flory (w. 1789–1824) of Lancaster County.

On the far wall are frakturs that German-born immigrant Francis Portzline (1771–1857), of Union County, made for his family. His precise and colorful work often features a central heart with peacocks and/or other birds. A large Hessian soldier whirligig made in Kingston, N.Y., stands atop an elaborate painted blanket chest attributed to Johannes Bieber (w. 1783–) of Berks County. The owner, Johan Greismer and the date, 1797, are painted on the front. Though decorated chests are often associated with a woman’s dowry, the names of men appear almost as frequently, suggesting the term blanket chest is more appropriate. Beside the chest is a Lancaster County side chair, 1760–1780, with characteristic beaded, high-arching crest with relief-carved ears. Two of a pair of six Philadelphia fan-back Windsors, some branded by Joseph Henzy (1760–1806), and a pair of Philadelphia comb-back armchairs, ca. 1770, surround a nine-foot Pennsylvania sawbuck table. |

A folk art shelf frames early nineteenth-century chalkware figures made of molded plaster of Paris with painted details. Also on the shelf is turned Lehnware made by Joseph Lehn (1798–1892); one cup is signed “JBL 1882, Lancaster.” Below are chalkware portraits of Andrew Jackson and his wife, Rachel, and of George Washington. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(left) Flanking the vine and berry Chester County bookcase, ca. 1730–1750, is a Lancaster County watercolor of General Lafayette, 1825, and a grouping of Jacob Gross and family, ca. 1815, all by Jacob Maentel (1763–1863). “A dealer convinced us to buy the family group in the 1950s,” says the wife. “I didn’t understand the prices for folk art at the time but he told me I would never regret it—and he was absolutely correct.”

The sculptural quality of chairs by William Savery (1721–1787) of Philadelphia is evident in this pair, ca. 1750s, centering the porringer table, and in the figured maple armchair. The George Hoff Lancaster tall clock, ca. 1768, is sulfur inlaid with a distelfink (thistle finch). “I bought this clock mainly because the inlay relates to imagery on frakturs,” notes the wife. The portrait by Duxbury, MA., physician and folk painter Rufus Hathaway (1770–1822) is pivotal in the attribution of the dozen other examples of his work because of the original bill that states: Duxbury April 29, 1793/Capt. Sywaners Sampson to Rufus Hathaway/to painting one portrait £1-10-0/in frame & cloth -4-/gilding the frame -3-4/Received payment/Rufus Hathaway.

|

(right) The dramatic spread wing eagle with flag and shield has a forty-one inch wing span. It presides over an early Spanish-foot Massachusetts easy chair, ca. 1740, from the Long Island home of Henry Francis du Pont, beside which is a rare inlaid, spiral-turned, claw-and-ball foot Dunlap family stand from southern N.H., once owned by legendary dealer Israel Sack.

The rare Pennsylvania daybed, ca. 1720–1735, is probably by the same maker as the armchair in the following image. Above it is a portrait of an unknown New England woman, painted ca. 1830, attributed to J. Parsons, Parsonsville, ME., and illustrated in Lipman and Winchester, The Flowering of American Folk Art (Whitney, 1974). A Pennsylvania folk art bird tree, early to mid-nineteenth century, is in the manner of traditional Germanic decorative wood carvings.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

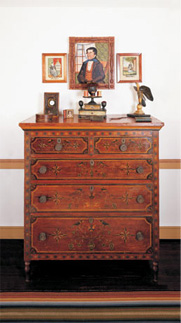

(left) Painted chests from the Schwaben Creek Valley in Northumberland County (referred to as Mahantongo Valley chests in early scholarship), feature highly stylized stenciled and freehand symmetrical decoration on a blue-green or red ground. Made in the 1820s and 1830s, they feature traditional Germanic motifs similar to those found on frakturs, while incorporating American federal period details such as painted quarter fans and geometric panels simulating inlay; the chest of drawers form is also non-Germanic.

Above the chest is a portrait of a gentleman by the “Reading Artist,” ca. 1820, painted on a handkerchief. It is flanked by 1820 watercolors of Hilen and Joanna Gilbert, by the same artist.

(below) The connection among many of the objects within this collection are the decorative elements found on frakturs. This bond is nowhere more pronounced than on this painted chest from Berks County, ca. 1820 (illustrated in Monroe Fabian, The Pennsylvania-German Decorated Chest [1978], 212–213).

|

|

The stylized lions and abstract tulips are by the same hand as those found on the frakturs of the “flat tulip” artist, Daniel Otto (1770–1822), linking him to the decoration of this chest.One of a pair of portraits of unknown sitters by Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), 1815, hangs over the chest and is representative of his “Border Period” paintings of about 1812 to 1819, in which his images are often against a light ground and have an ethereal appearance.

Two of a set of six Delaware Valley ladder-back side chairs are joined by an armchair attributed to the Ware family of New Jersey chairmakers. Over the Amish cloth toys is a propeller-operated whirligig. |

|

(Left) Folk art grouping.

(below) The family depicted in the four “shadows” or “profiles,” as this form of portraiture was referred to by the artist Ruth Henshaw Bascom (1772– 1848), were likely among her network of family and friends whom she tended to draw. Making profiles since 1801, Bascom became a professional artist in 1828 at the age of 56, and traveled around New England creating over 1,000 life-size bust portraits. The wallpaper hat box sits on a painted blanket chest.

|

|

|

|

|

|