|

| Home | Articles | The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts: Forty Wonderful Years |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1 (top): Accomack Room in MESDA, eastern shore of Va., ca. 1785. The furnishings in this room are primarily from Baltimore and Annapolis, Md. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc.

Fig. 2 (bottom): Chowan Room in MESDA, northeastern North Carolina, 1755. The early 18th-century furnishings are primarily from South Carolina, Virginia, and North Carolina. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc. |

Over the past forty years, the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, has come to be recognized as the preeminent museum devoted to collecting, exhibiting, and studying early Southern decorative arts and material culture. The museum has expanded from its original fifteen rooms and four galleries to the current twenty-two rooms and seven galleries. There are about 3,000 objects in the collection, most of which date from the late seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth century. Through its renowned research program, 76,000 craftsmen have been identified and recorded working in 126 trades; 30,000 objects in public and private collections are recorded in the photo files. All of these resources are available for study and perusal by scholars and the general public.

While MESDA serves as a central resource for the arts of the early South, it was founded in part to provide a context for the restored historic town of Old Salem in Winston-Salem. Established in 1766, the community of Salem was the governing center for the North Carolina Moravians, a German Protestant group that helped to form the cultural heritage of the Carolina Backcountry. In 1913 Salem was incorporated with the neighboring industrial town of Winston, merging as the new city of Winston-Salem. Fortunately, many of Salem’s original buildings remained in use, though suffering from disrepair and alteration. Interest in preserving and capitalizing on Salem’s early history resulted in the establishment in 1950 of a historic museum town, Old Salem Inc. Old Salem prospered and developed under the dedicated and watchful eye of Frank L. Horton, for more than twenty years the museum’s first director of restoration; currently the town contains seventy buildings, more than twenty of which are used by Old Salem for interpretive purposes. While Horton understood the Moravians, their architecture, their town, and their decorative arts, his broader vision was to establish a context for Old Salem within the American South. His dream was realized as the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, which was built on the fringes of the historic district.

When MESDA opened, Horton’s intent was to have the rooms—the architectural elements of which were retrieved from threatened southern homes—arranged “to show as a study collection, the arts and crafts of the South…in groups according to style, period, and provenance”1 (Figs. 1–2). This approach was in contrast to the Old Salem house museums, which reflected a particular family, trade, or household, at a specific time, and with the furnishings—from pottery mugs to desks and bookcases—consisting of Moravian originals whenever possible.

During the past fifty-five years, Old Salem has focused its collecting, research, and study on the Moravians, while for the past forty years, MESDA has concentrated on the states covered by the museum’s mission: Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia. This systematic approach has allowed MESDA to accurately define regional and cultural characteristics, distinguished as the Chesapeake, the Backcountry, and the Lowcountry.

The MESDA collection has two components: regional decorative arts including furniture, paintings, art on paper, textiles, ceramics, silver and other metal wares, firearms, glass, books, and prints; and imported accessories known to have been in the South, such as English, German, and Chinese export ceramics; English candlesticks and fireplace equipment; and European and English glassware. The collection also has pieces made by women, Native Americans, and African Americans.

In celebration of its fortieth anniversary, MESDA has published Southern Perspective: A Sampling from the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. This new book illustrates forty objects from the museum’s permanent collection, some of which are recognized as icons of Southern decorative arts. The following objects provide a sample of those represented in the publication. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Court cupboard, southeastern Va., 1660 – 1680. Oak with yellow pine and walnut. H. 49 7/8, W. 50, D. 18M/, in. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc.

|

One of the most recognized pieces in MESDA’s collection is this court cupboard (Fig. 3), one of only two known surviving Southern examples. It was made in southeastern Virginia between 1660 and 1680, and is one of the earliest pieces in MESDA’s collection. Court cupboards were most frequently found in estate inventories of wealthy Virginians in the eighteenth century, although MESDA’s research index has recorded one from as early as 1647 in Northampton County, Virginia. The most unusual characteristic of MESDA’s cupboard is the shelf above the cabinet; generally, a court cupboard is arranged with the shelf below the cabinet. Frank Horton acquired this piece in 1947, and it has been in MESDA’s collection since the museum opened in January 1965. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 4: Secretary with bookcase, Robert Walker (1772–1833), Charleston, S.C., 1812–1820. Mahogany, cedrela, and mahogany and satinwood veneer with ash, mahogany, and cedrela, brass, glass, and reproduction green felt. H. 83 1/8, W. 42 1/4, D. 21 1/4 in. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc. |

|

While many pieces of furniture in the collection are by unknown makers, some can be attributed to schools of cabinetmaking, and there are also pieces by identified makers. One of the latter is the secretary with bookcase by Robert Walker of Charleston, South Carolina (Fig. 4). Walker was born in Scotland in 1772, moved to Charleston by late 1795, and became an American citizen in 1799. He apparently enjoyed great prosperity, because at his death in 1833 he left an estate of a higher value than that of any other craftsman of the time. This secretary with bookcase still retains Walker’s label. MESDA is also very fortunate to own Walker’s personal copy of the Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book, by Thomas Sheraton (1791), which is marked throughout with Walker’s stamp.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Elizabeth Boush (ca. 1753–ca. 1810), The Sacrifice of Isaac, Norfolk, Va., 1768–69. Silk tent stitch on silk ground. 19 1/2 x 11 1/2 inches. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc. |

The embroidered inscription along the bottom edge of The Sacrifice of Isaac (Fig. 5) reads: “Elizth Bousch Workd this Peice at E. Gardners 1768 9.” This information makes this the earliest piece of American needlework to feature the name of the teacher, student, and the date; unusual in general considering the vast numbers of anonymous needlework. Elizabeth Boush, who was born around 1753 and died before 1810, attended Elizabeth Gardner’s school in Norfolk, Virginia. Gardner advertised in 1766 that she was opening a boarding school in Norfolk where she would teach “Embroidery, tent work, nuns do. queenstitch, Irish do., and all kinds of shading.” She married Freer Armston in 1769, and then advertised under the name of E. Armston. The Armston family fled Norfolk with other Tories in 1775, eventually returning to England.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Medal by Charles Pryce and J. Sands, Baltimore, Md., 1824. Gold. 3 1/8 x 2 3/16 inches. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc.

|

|

While most of the pieces in the MESDA collection can be considered as household furnishings, there are some that are of a more personal nature. These objects fall into various categories, including clothing, jewelry, and documents. One of the smallest pieces in the collection is a gold medal made for the Marquis de Lafayette (Fig. 6). This medal was a personal ornamentation as well as a commemorative piece. It survives as one of the most striking examples of Southern gold work. Because Lafayette came to America’s aid during the Revolutionary War and was regarded as a hero, the United States Congress declared him an honorary citizen and invited him to tour the United States as an official guest in 1824. This medal was presented to Lafayette while he was in Baltimore, and he wore it on a sash during his visit. It is replete with patriotic symbolism, and on the reverse bears the names of fourteen “Young Men of the City of Baltimore.” It is signed by the maker, Charles Pryce, and the engraver, J. Sands. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

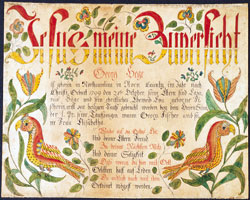

Fig. 7: George Hege fraktur by the “Ehre Vater Artist,” Friedberg, N.C.,ca. 1800. Watercolor and ink on wove paper. 12 1/8 x 15 1/4 inches.

Courtesy of Old Salem Inc.

|

A fraktur is a document that is both personal and commemorative. Most of the Southern fraktur were produced in the Backcountry, and MESDA has about fifteen from Virginia, North Carolina, and Maryland. The majority are birth and baptismal certificates, also called by their German name, taufschein, and the text on all but three is written in German. They are colorful and express a certain whimsy in addition to the important genealogical information that they contain. A well-known group of fraktur was produced by an anonymous artist known as the “Ehre Vater Artist.” Works by this artist’s hand are documented from Canada to South Carolina, and several were painted for Moravian families in North Carolina. Figure 7 commemorates the birth and baptism of George Hege, who was born on October 21, 1799, in the Moravian town of Friedberg, North Carolina, near Salem. The wove paper on which this fraktur is painted contains the Salem paper mill’s watermark, proving that the artist purchased the paper in Salem and painted the taufschein in the vicinity. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Ceramic lion doorstop attributed to Solomon Bell (1817– 1882), Strasburg, Va., ca. 1850. Earthenware with lead glaze over slip wash, with manganese dioxide and copper oxide. H. 11, W. 6,

L. 14 1/2 in. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc. |

|

Some of the best examples of Backcountry whimsy are found in the pottery, and MESDA’s lion doorstop, affectionately named Winchester, is a Southern icon (Fig. 8). This cheerful piece is attributed to Solomon Bell of Strasburg, Virginia, and dates to about 1850. There were four potters in the Bell family: the father, Peter, and his sons, John, Samuel, and Solomon. Solomon created a wide variety of utilitarian and decorative objects in clay, both stoneware and earthenware, and his modeled clay animal figures are his most expressive products.

Much is known about the society and culture of the early South, and the household objects that survive provide valuable insights into the lifestyles of the owners and the skill of the craftsmen who created them. Fortunately, there were also splendid portrait and landscape painters working in the South who recorded the people and their natural and built environment. One lovely portrait is thatof Judith Gist Boswell, attributed to Matthew Harris Jouett (1788–1827) (Fig. 9). Both the sitter and the artist were from Kentucky. Judith Gist was born in 1788 and died after 1834. She married a Lexington, Kentucky, physician, Dr. Joseph Boswell, who died in 1834. Boswell’s portrait immortalizes her as a young woman and was probably painted circa 1818–1822.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 9: Matthew Harris Jouett (1788–1827), attributed, Judith Gist Boswell (1788–after 1834), Ky., ca. 1818–22. Oil on poplar board, 28 1/16 x 22 13/16 inches. Courtesy of Old Salem Inc. |

Her dress, shawl, and hair are stylish for the time, and the somewhat abstract manner in which they were painted leads the viewer to focus on her calm face and eyes. Matthew Jouett spent most of his life painting in the South—primarily in Kentucky, New Orleans, and towns along the Mississippi River—except for the four months that he worked with Gilbert Stuart in Boston. Unfortunately, Jouett did not sign or date any of his paintings. Besides adding to its collection, another of MESDA’s ongoing objectives is the regular publication of new information about Southern craftsmen and decorative arts. The museum’s first book, published in 1966, was The Arts and Crafts in North Carolina, 1699–1840, by James H. Craig.

|

|

|

Since then, MESDA has published four large monographs; several exhibition catalogues; a scholarly journal, the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts; a newsletter, the Luminary, which is issued twice a year; and three catalogues/guides to the collection. In honor of its fortieth anniversary, MESDA hopes that its latest book, Southern Perspective, and the sampling presented here will help introduce the museum to new constituencies and to reacquaint longstanding friends with its stunning collection of early Southern decorative arts.

|

|

Paula W. Locklair is vice president of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) and the Horton Center Museums of Old Salem Inc. She was Curator of Collections from 1975 to 2001 and Director of Collections from 1987 to 2001.

|

|

| 1 Frank L. Horton, The Magazine Antiques (January 1967). |

|

|

|