Eric Gill at the Victoria and Albert Museum: New Sculpture Display

|  | |

| LEFT: Fig. 1: Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Age of Bronze, 1876. Bronze. © V and A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Given by the artist (A.33-1914). RIGHT: Fig. 2: Eric Gill (1882-1940), Mankind, 1927-1928. Hoptonwood stone. © Courtesy of the artist's estate / The Bridgeman Art Library. Tate (N05388). | ||

Eric Gill at the Victoria and Albert Museum: New Sculpture Display

by Ruth Cribb

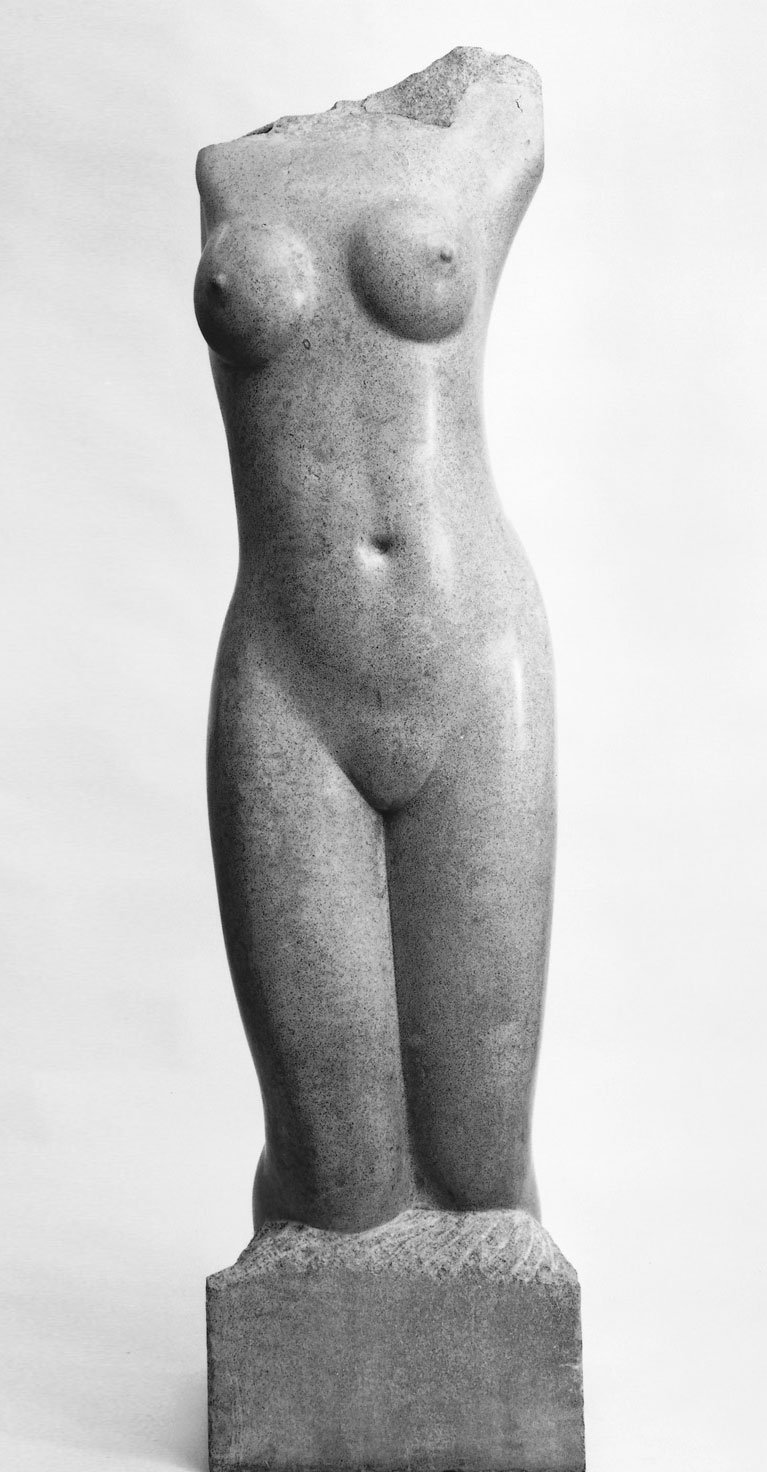

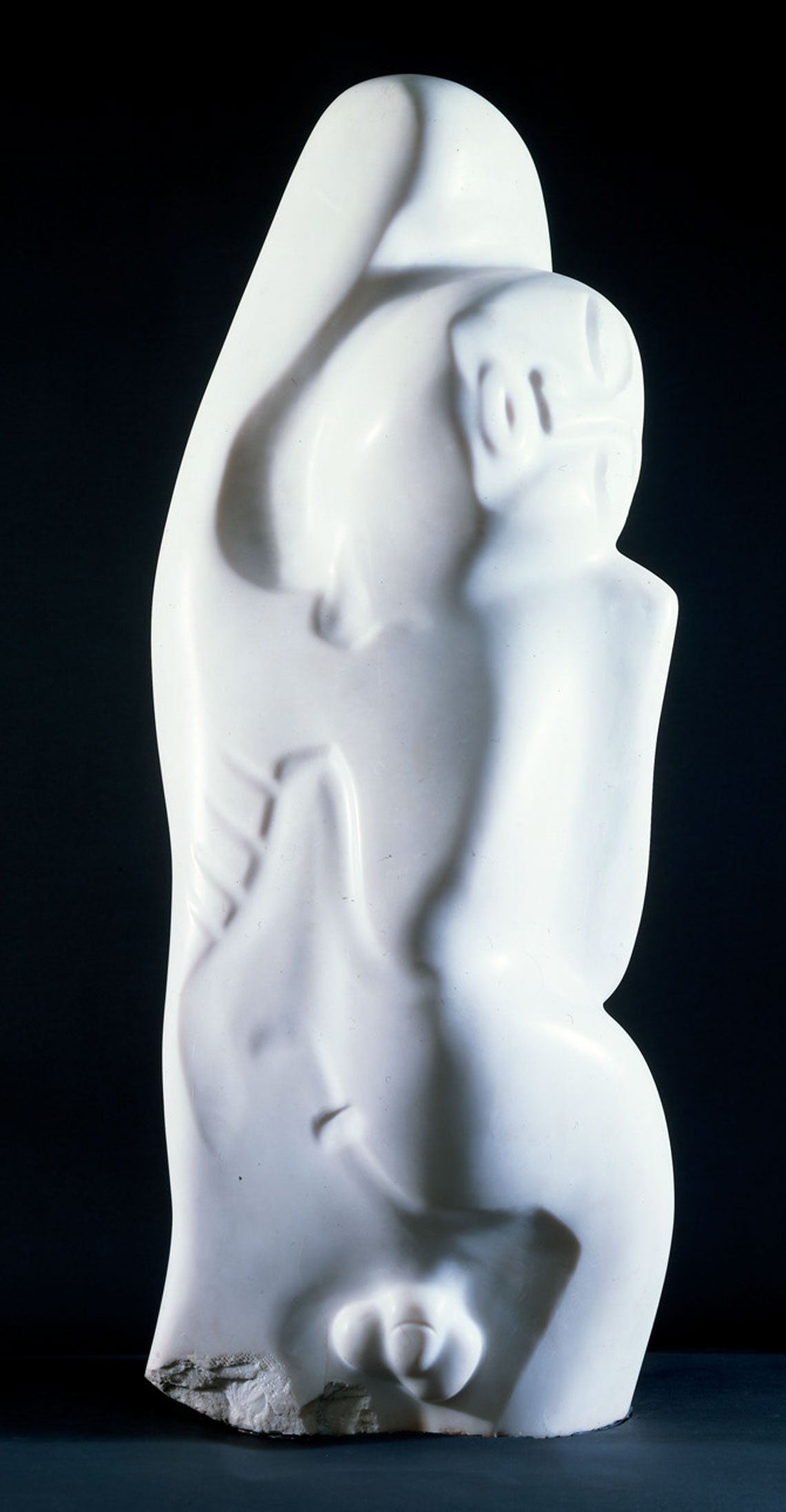

The V and A's unique collection of work by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), given to the museum by the artist in 1914, dominates its new sculpture display in the same way his revolutionary approach dominated the development of European sculpture from the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. The Age of Bronze (Fig.1), one of Rodin's most controversial sculptures, exemplifies his obsession with movement, tension, and the autonomous figure; when it was first exhibited, viewers believed it had been cast from the life. The other key artist featured in the new display is Eric Gill (1882–1940), whose monumental Mankind (Fig. 2) is displayed nearby. He, like Rodin, was an influential but isolated figure, and is typically constructed as an exception to the rule in the conventional history of British sculpture.

In Britain in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, sculptors were looking to Renaissance Italy and artists like Rodin in France in order to break free from the formulaic and static figures of neoclassicism. Their idealised forms became known as the New Sculpture, and Frederick, Lord Leighton and Alfred Gilbert were among its leading figures. Modelling was the key process of the New Sculpture in Britain, whereby the artist created a clay model that was then translated into bronze or marble by a trained craftsman. However, by the end of World War I and the influence of "exotic" objects and abstraction, this method was rejected in favour of direct carving, whereby the artist who first conceived the work was the one to execute it. This method radically altered the sculptural form. The most enduring and well known of this generation of sculptors are Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore. Often, these two strains of British sculpture are displayed separately, their continuities downplayed in favour of an impression of rupture — of the modern breaking with the traditional. The V and A's positioning of works by Rodin and Gill reflects the importance of these artists on both the New Sculptors and modernists in Britain and highlights the continuities between the two groups.

| |

| Fig. 3: Leon Underwood (1890-1977), Mindslave, 1934. Marble. © V and A Images, Victoria and Albert Museum, London / Courtesy of the estate of Leon Underwood. Given by the artist's son, Garth Underwood (A.1-1981). |

This interest in direct action upon the material by the sculptor was seen to be in a sense "truer" to the material than the traditional method. Gill was one of the most influential advocates of this theory. Associated with this new technique was the increasing influence of hand-crafted and small scale objects from non-European countries. The interest in these objects and processes is evident in works such as Mindslave carved by Leon Underwood (1890-1974) (Fig. 3). The change in scale, materials, techniques, and styles came to be seen as a dramatic break with tradition, a rejection of all naturalistic and monumental sculpture. That said, there were continuities in style and techniques, as well as many sculptors, including Gill, who did not follow the new trends into abstraction.

Born in Chichester in 1882, Gill went to the local technical and art school and learned decorative lettering before being apprenticed as a draughtsman to the London architect William Caroe in 1900. During this time he took evening classes in stone masonry and letter cutting at the Westminster Technical College, and most importantly for Gill's future career, he also learned lettering under the calligrapher Edward Johnston at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. Among artists in the late nineteenth century there was a revival of interest in medieval craft, specifically in the English stone carving tradition. Architectural decoration had gone out of fashion, but Alfred Stevens (1818-1875), one of the most influential sculptors working in the nineteenth century (and whose work can be seen as a bridge between the museum's displays of neoclassical work and the New Sculpture), was among those who worked with architects' firms to elevate the status of architectural sculpture. Many of the New Sculptors had, before attending the Royal Academy Schools, been apprenticed to and trained with stone masons or architectural carving firms. For instance, Harry Bates's (1850-1899) first tasks on joining the firm of Farmer and Brindley was to learn to carve simple roundels, rosettes, and foliations. He described himself as a "stone carver" while taking evening classes in modelling and drawing at one of the newly created art colleges in London. Gill never attended the Royal Academy schools, however, like the New Sculptors, he believed that the reunion of sculpture and architecture was one of the most important tasks of the modern artist.

It was while Gill was working with Johnston that he produced three pieces of lettering for Johnston's Manuscript and Inscription Letters, published in 1909. The book was designed so that the pages could be removed and used as templates for students and amateur artisans. These three reliefs (featured in the new display) were given by Gill to the V and A in 1931 for the use of students at the Royal College of Art, foreshadowing the continuous influence of Gill's work on letter cutters and calligraphers.

Direct carving and truth to materials were taken up enthusiastically by a new generation of sculptors after World War I; Frank Dobson and Maurice Lambert among them. They were concerned with representations of the figure, specifically the abstracted and the fragmented figure, as Rodin had been; however, they also simplified the form to distance it from the heroic and ideal figures of the New Sculpture. The new generation shared with Gill the sense that art in general, and sculpture in particular, could be a vehicle for changing society for the better, and many of them hoped to break down the boundaries between fine art and craft by reducing the size of some of their sculptures in the hope that they could be bought by more people. For Gill this social engagement was inextricably linked with his Catholicism, to which he had converted in 1913.

In 1907 he and his apprentice, Herbert Joseph Cribb, had moved to the village of Ditchling in Sussex (although Gill still kept a studio in London). It was here in 1921 that, with Hilary Pepler and Desmond Chute, Gill and Cribb established the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic — a Catholic medieval-style artists' guild. Gill believed that the moral good of art was expressed not only through the forms represented, but in the virtuous processes involved in conceiving and carving the work — uniting the long separated roles of artist as designer and artist as skilled artisan. When he received commissions for public works, he often subverted the secular meaning of his sculpture to represent his own religious priorities. Of his Prospero and Ariel, made for the BBC headquarters in central London, Gill said that the figures "are as much God the Father and Son as they are Shakespeare's characters," and he marked the figure of Ariel with Christ's stigmata.

|

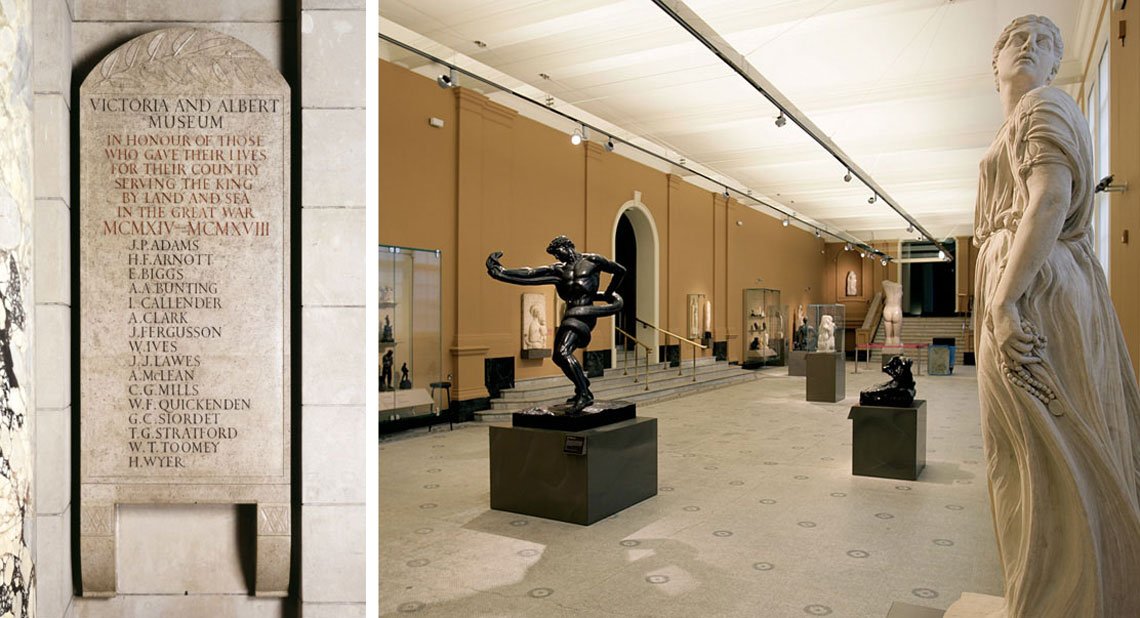

| LEFT: Fig. 4: Eric Gill (1882-1940), designer, and Joseph Cribb (1892-1967), carver, Memorial tablet to the V and A Museum personnel killed in World War I, 1919-1920. Hoptonwood stone with painted incised letters. © V and A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London (A.4-1999). RIGHT: Fig. 5: Sculpture in Britain 1600-1950, V and A galleries opened in November 2006. |

As William Morris had discovered, an individually created piece took time and was therefore more expensive to produce than mass-produced work. Gill and other sculptors also found that to be successful and prolific they needed the assistance of skilled craftspeople, eventually using them in a similar way to the New Sculptors. Gill's commissions made it necessary for him to take on six apprentices after 1906, and he employed a further twenty-one assistants over the course of his career. Gill's 1919 World War I memorial at the entrance to the V and A (Fig. 4) encapsulates the contradiction at the heart of his methods and theories. The panel was designed by Gill, while the actual carving was completed by his assistant Cribb, therefore in opposition to the ethos of direct carving.

Gill is often seen as an outsider to the "progression" of modernist sculpture in England, however, he can also be seen to bridge the divide between the academic tradition and the avant-garde. In 1928 he was commissioned to lead a team of younger sculptors, including Henry Moore and Frank Dobson, to create reliefs of the Four Winds for the outside of the London Underground headquarters. His leading role demonstrates the high esteem in which he was held, despite the conservative nature of his religion and his lack of interest in non-European artefacts. The commission also illustrates that although the new generation of sculptors were interested in creating small-scale abstract works and experimenting with new materials, they were still seeking and receiving commissions for public works in the tradition of nineteenth-century artists.

Any change in style or artistic practice is often seen, in hindsight, as a breaking free of the shackles of tradition; however no new movement is entirely separate from what came before it, and there is always an overlap in which artists are working in differing ways and styles. The V and A's new display, which completes its presentation of sculpture in Britain from 1600 to the end of World War II, reflects the importance of both Rodin and Gill, despite their often cited positions as outsiders, and shows that although there were contradictions at the centre of Gill's practices, he was not alone in pursuing the romantic and idealised medieval traditions of craft.

|