Great American Folk Art at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum Part 1 by Ronald L. Hurst

|

PART I

by Ronald L. Hurst

When John D. Rockefeller Jr. established Colonial Williamsburg’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in 1957, he recognized that the collection needed to grow beyond its namesake’s initial gift of 424 objects. New discoveries, evolving scholarship, and mounting public interest in folk art all demanded that it do so. Mr. Rockefeller consequently established an endowment that funded the purchase of over 100 works during the first year alone. Among them were extraordinary landscapes, such as Edward Hicks’s Leedom Farm and arresting portraits like that of Harmony Child Wight, attributed to the Beardsley Limner.

Mrs. Rockefeller’s core collection primarily consisted of portraits, sculptures, and carvings. After 1957, new areas of interest were developed through the leadership of the museum’s subsequent directors, curators, and a number of insightful donors. Along with paintings and sculpture, strong holdings in textiles, painted furniture, pottery, and decorative useful wares continued to be developed. The collection now includes more than 5,000 examples of remarkable American folk art, many of which were gifts from philanthropic supporters. Still others have been purchased with funds contributed by individuals and groups such the Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections. Examples featured in this article, the first of two parts, illustrate a sampling of landscape views and portraits. The second article, to be published subsequently, will include three-dimensional objects such as painted furniture and folk sculptures, decorative arts, and genre scenes. All are indicative of the outstanding quality of the collections at America’s oldest folk art museum.

|

Edward Hicks (1780–1849), Leedom Farm, Bucks County, Pa, 1849. Oil on canvas, 40-1/8 x 49-1/16 inches. 1957.101.4.

Pennsylvania artist Edward Hicks is best known for his Peaceable Kingdom pictures, but he also painted a small group of Bucks County farm views during the final years of his life. Leedom Farm was completed just a few months before his death in 1849. Showing the land and stock of Newtown farmer David Leedom on a luminous May morning, the soft tones of the sky and the pastel hillsides in the distance give the picture a dreamlike quality. Leedom, his wife, and other members of their family are depicted, along with Hicks’s deceased childhood friends, Mary Twining Leedom and Jesse Leedom. Their inclusion was meaningful to both artist and patron. No work takes place in this picture; Hicks, a devout Quaker, envisioned this gathering of beloved friends and gentle animals as a final, highly personal statement about the serenity he wished for mankind.

|

Joseph Henry Hidley (1830–1872), Poestenkill, New York: Winter, Poestenkill, N.Y., 1868. Oil on wood panel, 18-3/4 x 25-3/8 inches. 1958.102.16.

Joseph Hidley created at least five views of his hometown, Poestenkill, New York. Together they provide a detailed visual history of growth and change in the village over the last ten years of his life. Since these paintings were probably commissioned by townspeople, it was important that each structure be easily identifiable. To accomplish this goal Hidley contrived an elevated viewpoint and turned each building to give the viewer a fuller pictorial description of its façade. Here, the artist’s residence, still standing today, is shown as the bright yellow house adjacent to the steepled Lutheran church. The fine quality of Hidley’s townscapes suggests that he had some professional training or was familiar with works by more accomplished artists, but little is known about his education as a painter. He is listed in local business directories of the period as a house and sign painter and a taxidermist.

|

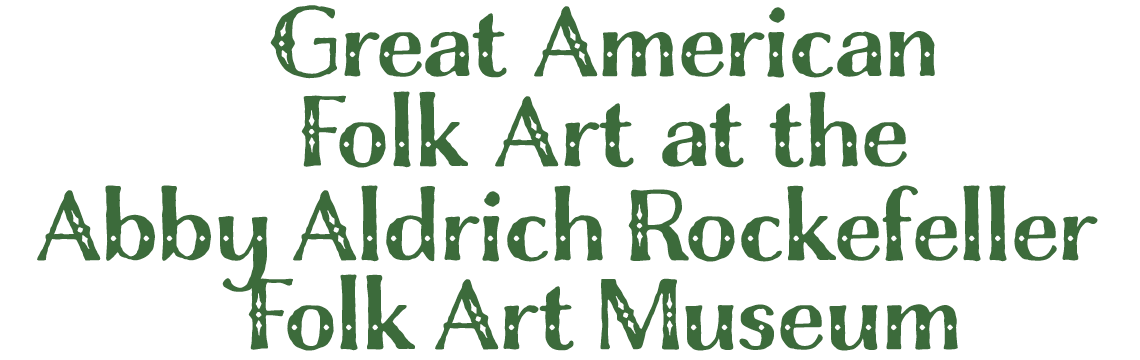

Charles J. Hamilton (1832–after 1881), Charleston Square, Charleston, S.C., 1872. Oil on canvas, 36-5/8 x 38-5/8 inches. 1957.101.5.

At the center of Charles Hamilton’s richly detailed view of Charleston, South Carolina, is the city’s grand 1841 Market Hall, a robust Greek Revival structure that still stands at Meeting and Market Streets. This composition captures the bustle and variety of commercial life in post-Civil War Charleston. Women balance baskets of produce, vendors serve their customers, the streets are full of horses and vehicles, and ships lie at anchor in the harbor. Despite the destruction and economic hardship brought to the city by a recent war and military occupation, Charleston is clearly on the rebound. Born in Philadelphia in 1832, Hamilton was at work there as a commercial carver by 1855. Although he produced tobacconists’ figures and other advertising tokens, he elegantly styled himself a “sculptor.” Several of his sketches for carved Indians, Turks, and other advertising figures survive. Hamilton later lived in both Washington, D.C., and Charleston, by then calling himself an “artist.”

|

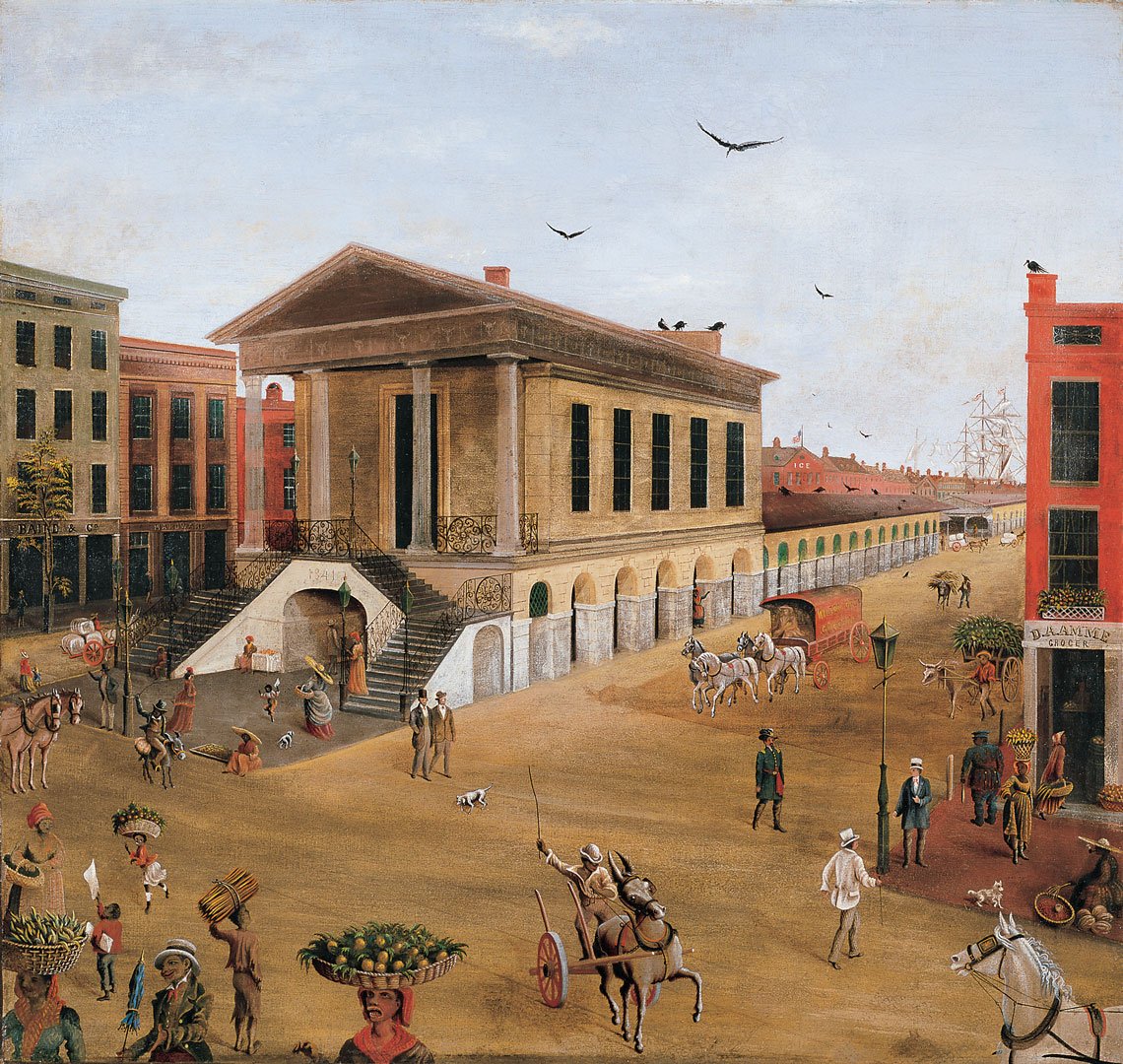

William Dering (active 1735–1751), George Booth, Williamsburg, Va., circa 1748–1750. Oil on canvas, 50-1/4 x 39-1/2 inches. 1975-242.

Portrait painter and dancing master William Dering lived and worked in Williamsburg, Virginia, during the late 1740s. An Englishman, his tenure in the colony briefly overlapped that of another English artist, Charles Bridges (1683–1740), with whose more academic work he was almost certainly familiar. Although Dering never achieved the more painterly style of Bridges, he was a willing imitator who used bold line and lively color to create memorial portraits like this one of young George Booth (d. 1777). The son of Mordecai and Joyce Armistead Booth of Bellville plantation in nearby Gloucester County, the young man’s self-assured pose, the sculptures flanking him, and the formal garden in the distance reveal his genteel status, while the hunting dog and bow are symbols of his manly achievements. Although many of these elements were derived from contemporary print sources, Dering’s handling of them is inventive and distinctively his own.

|

Attributed to the Gansevoort Limner, Deborah Glen, Albany, New York area, circa 1739. Oil on canvas, 57-1/2 x 35-3/8 inches. 1964.100.1.

Deborah Glen (1721–1786) was the daughter of Jacob and Sara Wendell Glen, who enjoyed extraordinary wealth and vast land holdings in colonial New York, and patronized the region’s best artists at an early date. This likeness of their daughter has long been attributed to an unidentified artist referred to as the Gansevoort Limner. With its saturated colors and carefully balanced composition, it represents the best of that painter’s works. Family history indicates that eighteen-year-old Deborah’s imposing full-length portrait was painted at the time of her 1739 wedding to the prosperous John Sanders, a theory that accounts for the richness of her costume. The beautifully patterned gown, the embroidered formal apron, and even the costly shoes were meant to record for posterity the good taste and social preeminence of the family.

|

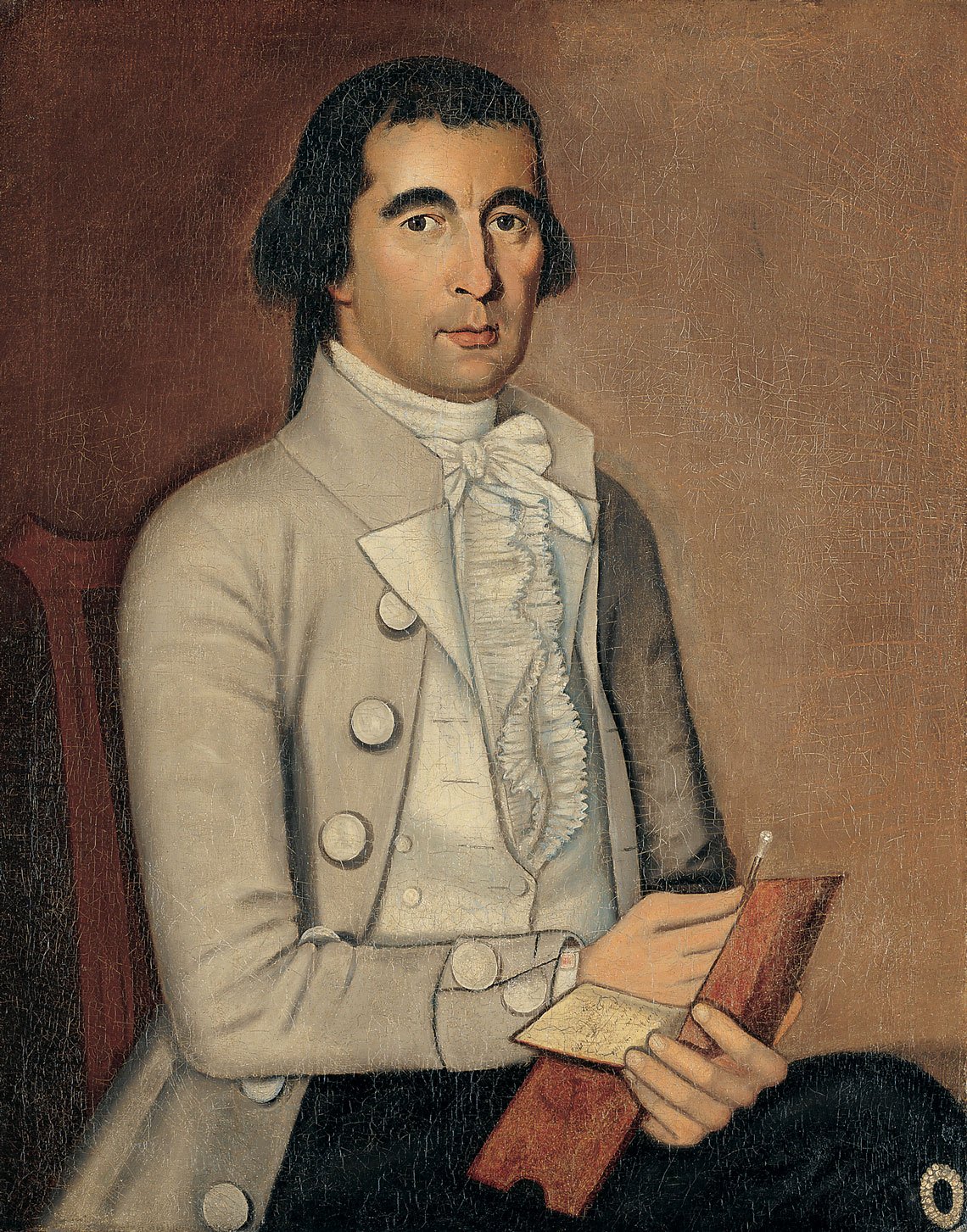

Attributed to the Beardsley Limner (active 1785– 1805), Harmony Child Wight, probably Sturbridge, Mass., circa 1786–1793. Oil on canvas, 31-1/4 x 25-1/2 inches. 57.100.10.

The wife of a Sturbridge, Massachusetts, cabinetmaker, Mrs. Harmony Child Wight (possibly 1765– 1861) exhibits all the fashionable trappings of the day, including an elaborate ruffled and beribboned bonnet, a black silk neck handkerchief, and embroidered gloves. Her face is carefully painted and her steady gaze conveys a sense of personal strength. It has been surmised that Sarah Perkins may have been the Beardsley Limner, whose name is derived from the portraits of Elizabeth and Hezekiah Beardsley of New Haven, now in the Yale University Art Gallery. Portraits by this artist date after the Revolutionary War and can be documented to Connecticut and Massachusetts towns along the old Boston Post Road.

|  |

Artist unidentified, John Mix and Ruth Stanley Mix, Connecticut, probably 1788. Oil on canvas, 32-1/2 x 25-1/2 inches. Gifts of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. 40.100.1 and 40.100.2.

The personal traits of John (1751–after 1788) and Ruth Stanley Mix (1756–1811) are clearly conveyed in their portraits: strength and business sense in him, fashion and domesticity in her. These compelling images have been variously attributed to a painter named McKay, to Abraham Delanoy, and to Reuben Moulthrop. The uncertainly lies, in part, in the different techniques used to delineate the sitters’ faces, hands, and garments. While the faces are carefully painted and anatomically correct, the hands are adequate at best, and the clothing was swiftly executed with broad, flat areas of color. The faces and hands may represent the work of two artists, or the disparate approaches may simply indicate one artist’s desire to emphasize the subjects’ faces. Acquired in 1940, these were among the last examples of folk art purchased by Mrs. Rockefeller.

|

Attributed to Joseph H. Davis, The Tilton Family, probably Deerfield, N.H., 1837. Watercolor, pencil, and ink on wove paper, 10 x 15-1/16 inches. 1936.300.6.

The Tilton Family is among the best of Joseph H. Davis’s known work and one of several portraits by the painter owned by the museum. Approximately 135 watercolor portraits are attributed to this itinerant artist. The most striking feature in this particular scene is the patterned floor covering on which Davis has placed the subjects, their furniture, and their cat. Such abstract designs were likely inspired by stenciled patterns, painted floor cloths, or woven carpets. The chairs and table, unrealistic in their bold decoration, presumably represent the painted “fancy” furniture common in the l830s.

|

Unidentified artist, The Prodigal Son Reveling with Harlots, Pennsylvania, circa 1790. Watercolor and ink on paper, 5-15/16 x 7 inches. 1959.301.4.

Images illustrating various episodes from the parable of the prodigal son were popular teaching tools for eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century moralists. Often relevance was enhanced by depicting the characters in contemporary dress. This picture is notable for the bright colors used in the figures’ clothing and rich pattern on the table.

|

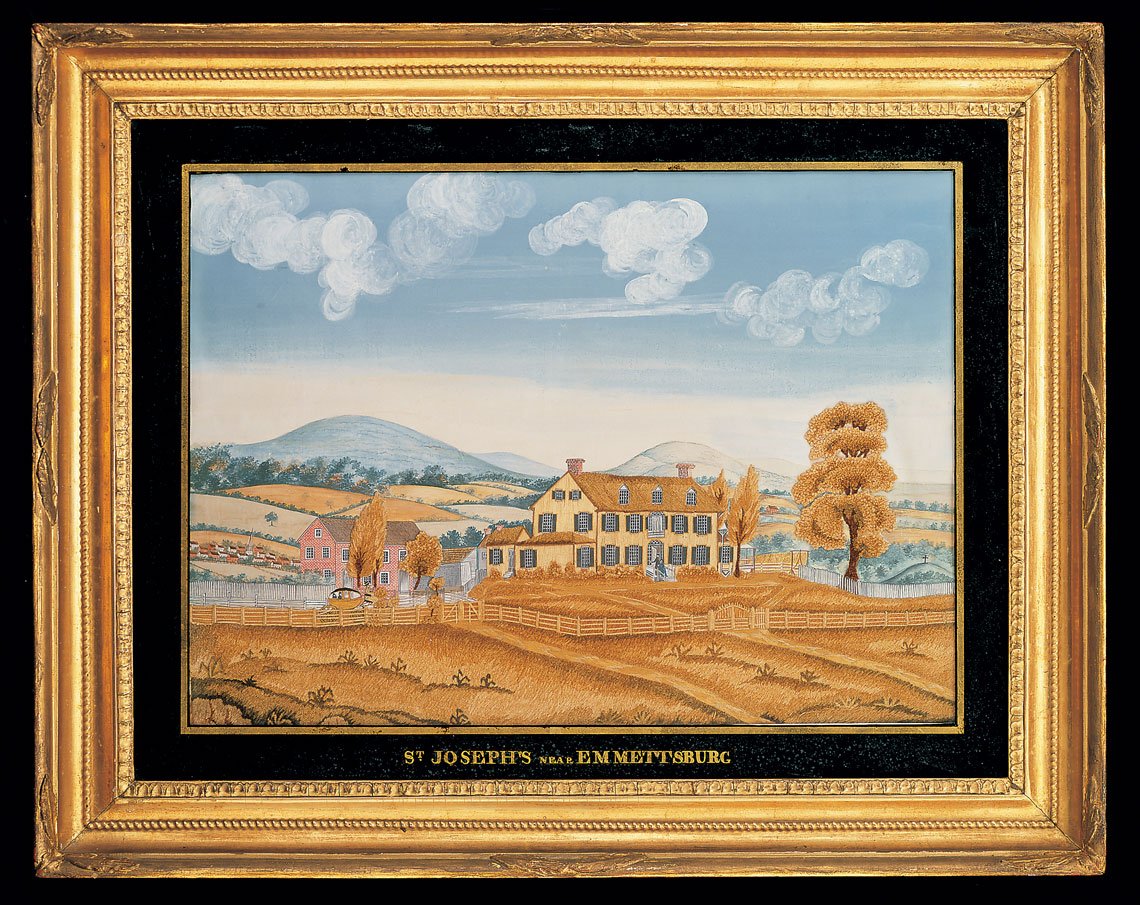

Unidentified artist, St. Joseph’s near Emmettsburg, Emmittsburg, Md., circa 1825. Silk embroidery and watercolor on silk, 16-1/4 x 22-1/2 inches. 1979.602.2.

Buildings were favorite subjects for Southern needleworkers, most of whom were school-age girls. This highly detailed scene depicts St. Joseph’s Academy in Emmitsburg, Maryland, established in 1809 as a “female academy” by Elizabeth Anne Bayley Seton (1774–1821). The school’s main building was recorded in embroidered pictures by a number of its young scholars. Here the unidentified maker combined the textural qualities of silk and chenille threads with the painterly detail of watercolor on a silk ground to achieve a high degree of accuracy. The work, with its original frame and églomisé mat, was acquired by Mrs. Rockefeller in 1935 while furnishing Bassett Hall, the eighteenth-century home restored by the Rockefellers for their private use while in residence in Williamsburg.

For information or to visit the new Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, call 1.800.HISTORY or visit www.colonialwilliamsburg.org.

Ronald L. Hurst is vice president of collections and museums, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2007 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|