|

| Home | Articles | Early Protective Covers for Upholstered Furniture: Fit, Fabric, and Applicability to Today's Interiors |

|

|

Fit, Fabric, and Applicability to Today's Interiors

|

|

by Deborah E. Kraak

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Robert Dighton (1752-1814),

January, England, 1784.

Mezzotint on paper, 19.93 x 9.93 inches.

Courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

Cotton or linen cases were used even during the cold weather months. This cover is trimmed with what appears to be a woven fringe; ruffles made of the same fabric as the cases were another option.

|

Visitors to museums or historic houses, as well as readers of home décor catalogues or shelter magazines, may have noted the increasing prevalence of slipcovers on chairs and sofas. Removable coverings for upholstered furniture have a long history of use, with remarkable variety in what they were called, what they covered, and what they were made of (Figs. 1, 2). This article focuses on examples used from the seventeenth through the early nineteenth century.1

During the period being presented, the word cover denoted the outermost layer of fixed upholstery. A removable covering was usually called a case, sometimes further described as a false case. In Scotland, cases were also known as slips, a term that lingers into the present with slipcases for books and slips for pillows. During the nineteenth century, cover or loose cover gradually superseded the word case. Because case was the most widely used term in the period under discussion, it is the term of choice for this article.

Cases were used to keep expensive surfaces clean, shield them from the sun's bleaching rays, and protect the upholstery underneath from wear and tear. They were practical on an aesthetic level, too. Older styles of upholstered furniture could be updated with a set of cases in a smart new fabric, while a set of matching cases could unify a room furnished with mismatched upholstery. Traditionally, cases were only removed when the most esteemed visitors came to call.

|

Cases for Early Seating Furniture and Cushions

There were two types of cases: loose-fitting and snug. Loose-fitting cases, usually made of cotton or linen, slipped over cushions or were tied onto furniture with narrow fabric tapes (Fig. 3). The relaxed fit minimized abrasion to the expensive show cover fabric when the cases were put on or removed. Sometimes loose-fitting cases even covered seating furniture that was left "in the canvas," i.e., without a fixed show cover.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Johann Zoffany (1733-1810),

George, Prince of Wales and Frederick,

later Duke of York (detail), 1764.

Oil on canvas. Unframed: 44 x 50-3/8 inches .

The Royal Collection © 2007,

Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II.

The cases on the sofa, chairs, and stools match the color of the show covers, a practice advocated by Chippendale. The cases on the arms of the window stool have been removed, revealing the damask show covers.

|

Snugly fitting cases were made of fine textiles, from worsted wool to velvet, brocatelle, and needlepoint. They were also placed over seating furniture that had been left "in the canvas." They might have vents at the sides or middle of the back to make it simpler to ease them onto and off the furniture. They were secured to the frame with either tapes, laces, hooks and eyes (Fig. 4), or via eyelets that slipped over short metal pegs in the frame; a method used for an early eighteenth-century suite of chairs at Houghton Hall in Norfolk, England.2 Although both types of cases were usually constructed as a single unit, they were also made in separate sections for a better fit. This type of construction is seen in figure 2.3

Silk, worsted wool, and leather cases

Inventories are an excellent source of information about the diversity of case fabrics and colors. The 1677, 1679, and 1683 inventories of Ham House, in Surrey, England, the seat of the Duke of Lauderdale, include a variety of late-seventeenth-century case materials, many of which continued in use into the eighteenth century in England and America (which usually followed English practices).4

|

At Ham House, matching sets of cases were usually constructed of varieties of lightweight silk or worsted wool (cloth woven from the straighter, shinier part of the fleece and professionally processed to retain its sheen). One silk mentioned was a crimson taffety (taffeta, a plain-woven fabric with a slight horizontal rib). Another was yellow or green sarcenet, either plain-woven or twilled (woven with a diagonal rib). Sarcenet could also be changeable (iridescent), clouded (now called ikat, the warp dyed or printed in a pattern prior to weaving), striped, or checked (purple and white). Silk cases declined in popularity after the early eighteenth century.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: John Hamilton Mortimer (1741-1779),

Self-portrait, England, ca 1760.

Oil on canvas, unframed: 29 x 24-1/2 inches.

Private collection.

Permission courtesy of Mallett, London & New York.

Notice the period construction details: loose fit, straight skirts, very narrow, rolled hem, placement of the white tape ties. The author wishes to thank costume historian and collector Mary Doering for bringing this image to her attention.

|

Two worsted cases are mentioned in the Ham House inventories: paragon (a coarse fabric which was sometimes calendered for a moiré effect) and serge (a twill weave with a worsted warp and a woolen weft). Only serge retained its popularity throughout the eighteenth century as a case fabric, particularly for formal rooms. Christopher Gilbert, in The Life and Work of Thomas Chippendale (1978), writes that Chippendale's neoclassical seating furniture was generally accompanied by a suite of serge covers in a color that matched the other textile furnishings, such as fixed upholstery and curtains (Fig. 2). Cases were typically green, blue, crimson (considered the most elegant color, perhaps because this was the most expensive dyestuff), yellow, or buff. Serge cases were used over upholsteries of worsted wool, silk, embroidery, tapestry, and sometimes leather, despite Gilbert's observation that chairs upholstered in leather or horsehair appeared not to need cases. For example, a circa-1780 inventory for Appuldurcombe Park, on the Isle of Wight in England, lists carved and Wedgwood-inlaid mahogany elbow chairs upholstered in green leather with green serge cases.

The partnership of furniture designers, upholsterers, and cabinetmakers John Mayhew and William Ince (1758/59-1803) provided several sets of shalloon cases for furniture at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, England, the home of the Duke of Marlborough. Most early American references to this lightweight, twilled worsted (sometimes hot-pressed to give it sheen) describe it as a lining fabric for clothing. However, Florence Montgomery, in Textiles in America (1984; 2007), cites references to the eighteenth-century use of shalloon for bed-hangings in Virginia and New York, so perhaps it was used here for cases as well.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Dolphin chair, Ham House, Surrey, England, ca. 1670. Beach wood and silk brocatelle cases with plain-woven linen lining, with red twill-woven wool forming the outside back of the cases. Courtesy of V&A Images. CT25680.

|

Leather cases, sometimes lined with flannel (made in the eighteenth century of wool woven to have a soft, spongy texture) or baize (loosely woven wool with a soft nap), seem to have been used when furniture was made of particularly precious materials and required substantial protection. For example, in 1765, Thomas Chippendale sold Sir Lawrence Dundas "leather cases&lin'd with Flannel" for "4 large Sofas Exceeding Rich" to match a set of "8 large Arm Chairs exceeding Richly Carv'd in the Antik manner and Gilt in oil Gold Stuff'd and cover'd with your own [crimson silk] Damask." The furniture, designed by Robert Adam and made for the Great Room of Dundas' London home, had a second set of cases made of crimson and white check (either cotton or linen).

Cotton and Linen Cases

Checks and Stripes of Cotton or Linen

There are few seventeenth-century references to cotton cases, one exception being the white cotton calico cases in the 1685 probate inventory of merchant George Corwin of Salem, Massachusetts.5 But from the 1750s onward, plain-woven cotton and linen check cases enjoyed a growing popularity in both America and England. They were used throughout the house, in bedchambers as well as parlors and dining rooms. Usually the checks were woven (not printed) in squares of white and another color (Fig. 5).

|

|

|

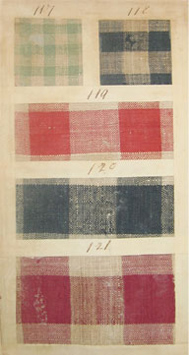

LEFT: Fig. 5: Page of woven linen furniture check fabric, Sample book of Benjamin & John Bower, April 9th, 1771, Manchester, England. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. RIGHT: Fig. 6: Cushion case for an easy chair made of plain-woven cotton, plate printed in England by Robert Jones, Old Ford, 1761-1780; wool and linen binding, cotton and wool fringe. Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Boxed cushion cases had seams turned to the outside and covered by woven tape that also reinforced the shape. Not all easy chair cushions were boxed, as demonstrated in a 1768 mezzotint by J. Finlayson of a J. Zoffany painting, illustrated in Anne Buck, Dress in Eighteenth-Century England (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1979), fig. 34. The chair and the large cushion have check cases.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Case for a chair seat, plain woven cotton and linen cloth, plate-printed in red, by Robert Jones, Old Ford, 1761. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

Note the long skirts and flat ruffle made with very small gathers. This effect can only be carefully approximated with modern reproduction fabrics, as they are a heavier weight than the original textiles.

Typical of cases in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, matching the motifs along seam lines was not a high priority.

|

Advertisements in the Philadelphia Gazette mention check fabric in blue (indigo), Saxon blue (a light shade), red, scarlet, crimson, green, and purple.6 Yellow check cases appear in paintings by English artist John Hamilton Mortimer. Check squares were 1/4, 1/2, 3/4, 1, and 1-1/4 inch, with larger sizes probably used for furnishings and smaller ones for clothing. Checked fabrics for cases also came in bolder patterns, similar to today's windowpane check, woven in a variety of colors with a large white field. There was also worsted furniture check, but such references are very rare.

In 1771, Philadelphia upholsterer Plunket Fleeson made furniture check cases for one of the most famous furniture commissions in colonial America: John Cadwalader's elegant Philadelphia mansion. The bill itemizes "fine Saxon blue Fr. chk for cases of 3 Sophas & 76 Chair Cases" and 152 yards of blue and white fringes, tape (possibly for ties), and thread for making the cases. There was also a charge for "fine blue Cotton Checks for a Sopa [sic] and 12 cases."7

|

|

|

|

|

|

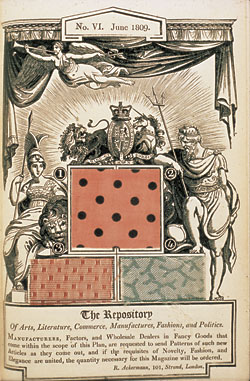

Fig. 8: Pink plain-woven furnishing cotton with black polka dots on a page of fabric swatches from the June 1809 issue of Rudolph Ackermann, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufacture, Fashions and Politics, published in London. Courtesy of Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.

Can a pattern usually associated with 1950s fuzzy dice be used for cases on neoclassical seating furniture? Yes. This fabric, called "the Oriental Pink," was illustrated in an issue that featured furniture "after the Grecian style," demonstrating just how unexpected authentic designs for case fabric can be.

|

By the end of the eighteenth century, striped cases were replacing checks in formal rooms, possibly because stripes were associated with the lines of neoclassicism. Made with bands of even or uneven widths, stripes came in a variety of colors often on a white ground. There were also multi-colored striped cases, such as the twill-woven linen selection proposed in 1796 for the Assembly Rooms in Edinburgh, Scotland. Striped cases remained fashionable well into the nineteenth century, whereas check cases came to be associated with rustic interiors and servants' quarters.

Copperplate and Woodblock Printed

Cottons and Linens

During the second half of the eighteenth century and into the early nineteenth century, copperplate- or wood block-printed cottons, linens, and fustians (fabric with a linen warp and a cotton weft) became popular for cases. They were typically reserved for the more private rooms of a house, where personal tastes were allowed more play. Printed motifs reflected the vogues for floral designs, Rococo patterns, Chinoiserie and Indian-influenced patterns, and Neo-classical, Gothic, and Egyptian revival imagery, among others. It was standard practice for printed textiles to be advertised not by the motif, but by the color of the design or by the color of the background.

Copperplate-printed cottons and linens (now called Toile de Jouy) have been a decorating classic ever since the printing technique was invented in Ireland in 1752 (Figs. 6, 7). Advertised in this country as "Copper Plate Furniture" or "copperplate furniture calicoes," these prints came in several colors, including blue, sepia, and purple, but -- as with silk -- red was considered the most elegant color for a copperplate-printed fabric. Fabric block-printed in two or more colors, generally called "chints" [sic] or "furniture cotton chints", could be used for cases. Sometimes, as in a set of three circa-1810 cushion cases at Winterthur, individual motifs could be cut out and appliquéd into a new composition on the ground cloth of the case.

|

Glazing case fabrics

Printed and woven textiles were sometimes glazed, that is, given treatments that imparted a glossy surface. When cases needed refreshing, they were taken apart, laundered, reglazed, and resewn. Until recently, it was generally assumed that it was only because highly-reflective surfaces were prized (to enhance the low-light conditions) during the eighteenth and nineteenth-century that furnishing fabrics were glazed. But textile historians have lately speculated that glazing was an early form of stain repellent that protected fabrics by helping them shed dust and spills, thus reducing the need for laundering. This was confirmed when the author recently discovered the following reference to reglazing furniture chintz in Miss Leslie's The House Book: or, a manual of domestic economy (1841): "The greater the gloss, the longer [the fabric] will keep clean." Methods of glazing cotton or linen case fabrics included starching and ironing or rubbing them with a smooth stone, a process known as "sleeking." Worsted fabrics were treated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries with a special heat-and-pressure process that heightened their shine and surface slickness.

Present Day Use of Cases

Today, whether decorating with antique furniture or historic reproductions, cases offer a time-tested way of protecting upholstery, unifying the look of mismatched pieces, or simply adding variety to a room. Although finding light-weight silks and worsteds in period colors that drape well is a challenge, a wide variety of checked and striped fabrics are readily available in virtually every price range, making them a convenient option for re-creating the look of period cases. There are many reproductions of antique copperplate- and woodblock- printed fabrics that faithfully or more liberally interpret original patterns. How to decide? Period illustrations, surviving covers, and historic documents demonstrate what fabrics were used for cases, how they were constructed, and how they may be re-created or evoked using the reproduction fabrics available today through high-end fabric companies. There are styles for every taste, and a little sleuthing can yield surprisingly fresh options that will give any interior considerable originality and verve (Fig. 8).

|

|

|

Deborah E. Kraak is a consultant specializing in historic textiles, costumes, and interiors. A resident of Wilmington, Delaware, she designs textile treatments for private homes, museums, and historic houses. She thanks Nancy Britton, Conservator of Upholstered Works of Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Natalie Larson, Historic Textile Reproductions, Williamsburg, Virginia, for their expertise and encouragement.

|

|

|

1. The following sources were resources for this article: Linda Baumgarten, "Protective Covers for Furniture and Its Contents," American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover and London: the Chipstone Foundations: 1993): 3-14. This excellent article contains bibliographic references to earlier works about cases; Geoffrey Beard, Upholsterers and Interior Furnishing in England, 1530-1840, (Published for the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts by Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1997); Pamela Clabburn, The National Trust Book of Furnishing Textiles (London: Penguin Books, 1989 edition); Wendy Hefford, The Victoria and Albert Museum's Textile Collection, Design for Printed Textiles in England from 1750 to 1850 (New York: Canopy Books, A division of Abbeville Press, Inc., 1997); Florence Montgomery, Textiles in America, 1650-1870 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, A Winterthur/Barra Book, 1984; reprinted by W. W. Norton, 2007); Margaret Swain, "Loose Covers, or Cases," Furniture History, vol. XXXIII, 1997, 128-133.

2. For information about snug-fitting cases made from show fabric, see Derek Balfour and Nicola Gentle, "A Study of Loose Textile Covers for Seat-Furniture in England between 1670 and 1731," in Wim Mertens et al., Ijdel Stof, Interieurtextiel in West-Europa 1600-1900, exhibition catalogue (Hessenhuis Antwerp, 2001-2002), 295-299.

3. This was pointed out to the author by Mark Anderson, Furniture Conservator at Winterthur Museum.

4. The Ham House inventories, and many others, are published in the journal Furniture History.

5. George Dow, Everyday life in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Boston: The Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1935): 278-279.

6. The Pennsylvania Gazette from 1728-1800 (Folios I-IV) is now available on CD-ROM and can easily be searched for words relating to fabrics. See Accessible Archives, Inc., www.accessible.com; 610.296.7441.

7. See Mark J. Anderson, Gregory J. Landrey, and Philip D. Zimmerman, The Cadwalader Study (Winterthur, DE: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1995). In 1995, when the Cadwalader furniture was the subject of an in-depth study sponsored by Winterthur Museum, check cases were made for straight-front and saddle-seat side chairs. The various reproduction cases were not based on period models, but had tight-fitting caps that were cut short to reveal the carving on the chair's front rails so museum visitors could see the carving, instead of being a loose-fitting case that came to mid-leg in order to protect the wood and the show cover.

|

|

|

|

|

|