Conservation of a Fabled Masterpiece The Fox and Grapes High Chest at the Philadelphia Museum of Art by Christopher Storb

“The Americans are said to be great Lovers of Fable,

and to reward those who can relate them; being much delighted

to hear Dogs, Horses, and other Creatures discoursing together.”

— Philip Ayres, Mythologia Ethica, or Three Centuries of Æsopean Fables in English Prose (1689)

|

Detail of the top of the high chest after restoration. |

|

by Christopher Storb

The Philadelphia Museum of Art has in its collections numerous objects with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez (d. 1815), in addition to the historic Mount Pleasant, the mid-eighteenth century house for which Jugiez created his most brilliant surviving carved domestic interiors. A sideboard table in the collection attributed to Jugiez has been described as “…perhaps the most sculptural piece of colonial American furniture,”1 while a richly ornamented high chest (Fig. 1) is one of the best known pieces of American furniture and a favorite of visitors who are captivated by its complexity of design, its superb craftsmanship, and the intriguing carved scene on the large center drawer in its lower section.

|  | |

Left Fig. 1: High chest, unidentified cabinetmaker with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–1775. Mahogany with yellow poplar, white cedar, yellow pine and brass. H. 96-1/4, W. 46-1/2, D. 25-1/4 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Mrs. Henry V. Greenough, 1957. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This photograph, ca. 1924, shows the chest in the condition it was first exhibited. The fox’s head, paw, and the leaves on the finials had been previously restored. The foliate scrolls, fret, and sections of the lower front rail appliqué are missing. Right Fig. 2: Design for a mirror illustrated on pl. 21 of Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred and Fifty New Designs (London 1761), adapted by Jugiez for the appliqué on the carved drawer. Jugiez made use of other plates in Johnson for the designs of the cartouche, finials, and flowering vine-carved quarter columns. | ||

|

Detail of the central drawer in the lower section of the high chest illustrated in figure 1 before restoration. Replacements made before 1924 include the head, neck, and right paw of the fox, as well as sections of the acanthus leaves and c-scrolls on the drawer and lower rail appliqué. Photography by author. |

|

Detail of the central drawer from the lower section of the high chest. The early wood replacements and modern nitro-cellulose lacquer have been removed. The “witness” shadows are left from the previous replacements. Photography by author. |

We are used to having scant information about the lives of the mostly anonymous craftsman who pursued their trade through earlier centuries, and such is the case with Jugiez. Jugiez’s nationality and circumstances of apprenticeship are unknown. Unlike the immigrant carvers James Reynolds and Hercules Courtenay, Jugiez never advertised as having arrived from London as the other two would do in 1766 and 1769 respectively. Between 1762 and 1783, Jugiez shared a business in Philadelphia with the carver Nicholas Bernard. Bernard and Jugiez made known that they could provide all manner of carving in wood and stone. They also offered an assortment of items for sale imported from London, including looking glasses, picture frames, chimney pieces, and ornaments for ceilings. Shortly after Bernard and Jugiez first advertised in The Pennsylvania Gazette on November 25, 1762, they were engaged in many of the most desirable commissions in Philadelphia, including producing a variety of architectural carving for St. Peter’s Church and the massive organ case (1763–1764), and creating the carved interiors at Mount Pleasant (completed 1765), the country seat of the privateer John Macpherson and his wife Margaret.

Throughout the eighteenth century, Jugiez continued to receive commissions from affluent patrons such as Benjamin Chew, John Cadwalader, and Samuel Powel, as well as from prominent Philadelphia cabinetmakers Thomas Affleck and Benjamin Randolph. He marched alongside James Reynolds and the carver’s float in Philadelphia’s Grand Federal Procession of July 4, 1788, and carved Ionic capitals for the central rotunda of the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1799.2 Little work is documented or attributed to him past the end of the eighteenth century, though in an 1803 letter to Samuel Mifflin discussing the construction of a stove for the U.S. Senate Chamber in Washington, D.C., architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe wrote, “and old Martin Jugiez renowned as the ugliest man in Philadelphia will do the carving, exactly in the stile of the stove of the Bank of Philadelphia….”3 Jugiez’s abundant production over a fifty-year career in Philadelphia, seemingly resulted in scarcely a city block that didn’t house chests, chairs, tables, clock cases, or architectural elements embellished with his remarkable sculptural carving.

|

Detail of the drawer in the lower section of the high chest after restoration. The carved figure of the fox on the en suite dressing table is intact and complete and provided information to replace the poorly restored head and paw of the fox on the high chest drawer during this treatment. Minor adjustments needed to be made when transposing the design of the head and paw due to the slight difference in size and position of the fox on each drawer. Losses to the acanthus leaves and c-scrolls were restored based on intact elements elsewhere on the chest. Photography by Graydon Wood. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. |

| |

Detail of the top of the right scroll molding on the high chest (in Fig. 1). Saw marks suggest that the foliate scrolls springing from the scroll moldings were purposefully removed rather than broken off, perhaps when the chest was relegated to a space with a low ceiling. A dozen case pieces from eighteenth-century Philadelphia are known that made use of these extravagant and difficult to execute terminations. They remain intact on only three objects: the case for the David Rittenhouse orrery at the University of Pennsylvania; the case for the David Rittenhouse astronomical clock at Drexel University: and Deshler family chest on chest in the collections of Colonial Williamsburg. While none of these surviving foliate scroll terminations were carved by Jugiez, they provide information about the general form of this element on the museum’s high chest. The foliate scrolls restored during this treatment are modeled in Jugiez’s characteristic carving style. Photography by the author. |

The high chest in figure 1 is an elaborate and sophisticated furniture form representing the considerable skills of this shop master, designer, journeymen, and carver. It has long been known as “The Fox and the Grapes High Chest,” after the pictorial narrative carving on the central drawer in the lower case, which depicts the Aesop fable of how easy it is to despise what you cannot get. Jugiez adapted his design for the fox and the grapes drawer appliqués from plate 21 of Thomas Johnson’s One Hundred and Fifty New Designs, (London, 1761), (Fig. 2).4 The dressing table, made en suite, is in a private collection; since 1976 it has been on loan to the Museum, where it has been exhibited alongside the high chest.

Carved pictorial narrative scenes on Philadelphia eighteenth-century furniture are known on only one chest on chest and two other pairs of high chests and dressing tables. One of the en suite pair (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) also features drawer appliqués based on a design by Thomas Johnson. A dressing table (Museum of Fine Arts Boston) and its en suite high chest that survives only as a base (Department of State) portray a phoenix and swan in rocaille settings. The chest on chest (Winterthur Museum) has a tympanum appliqué depicting a lamb and ewe. None of the carving on these other objects is attributed to Jugiez. Together, the three pairs employ carving that exceeds the most elaborate versions of high chest and dressing table forms described in the 1772 Philadelphia Furniture Price Book. On all three, the flower and leaf carved quarter columns, carving on the lower rails, fully carved side finials, and the carved fronds or foliates that spring from the scroll moldings of the cornices represent exceptional work for which a client would be charged additional fees.

|

Detail showing the reverse of the appliqué from the lower front rail of the bottom section of the chest. When the appliqué was examined during the current restoration, a pencil drawing of the design that was ultimately carved on the front was discovered on the back of the central quatrefoil form. Jugiez drew his design but then for an unknown reason flipped the appliqué and carved the other side. The nature of the drawing on the back confirms that Jugiez did not use patterns but would begin carving after rapidly sketching out his design on the wood blank to be carved. The back-cutting or beveling Jugiez used to make his appliqués appear more three-dimensional can be seen along the edges of the appliqué. |

|  | |

| Left: The high chest during restoration. This photograph documents the restorations made during the current treatment. The new wood appears several shades lighter than the original cabinetwork and carving. Wood restorations include new fret based on the witness shadows in the 1975 slides; portions of the appliqué on the lower rail; elements on the carved drawer, including the fox’s head and right paw; leaves and buds on the outside edges of the original side finials; and leaves on the original center cartouche; and the foliate scroll terminations of the scroll molding. Photography by Joe Mikuliak. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Right: The high chest after restoration. To complete and unify the treatment, shellac toned with dyes was applied as a finish. The Philadelphia Museum of Art devoted significant amounts of time and resources to the treatment of one of its treasured objects. Now reinstalled in the Patricia Sinnett Flammer gallery, the restored high chest, and its matching dressing table, will offer visitors insight into life and art in eighteenth-century Philadelphia. | ||

| |

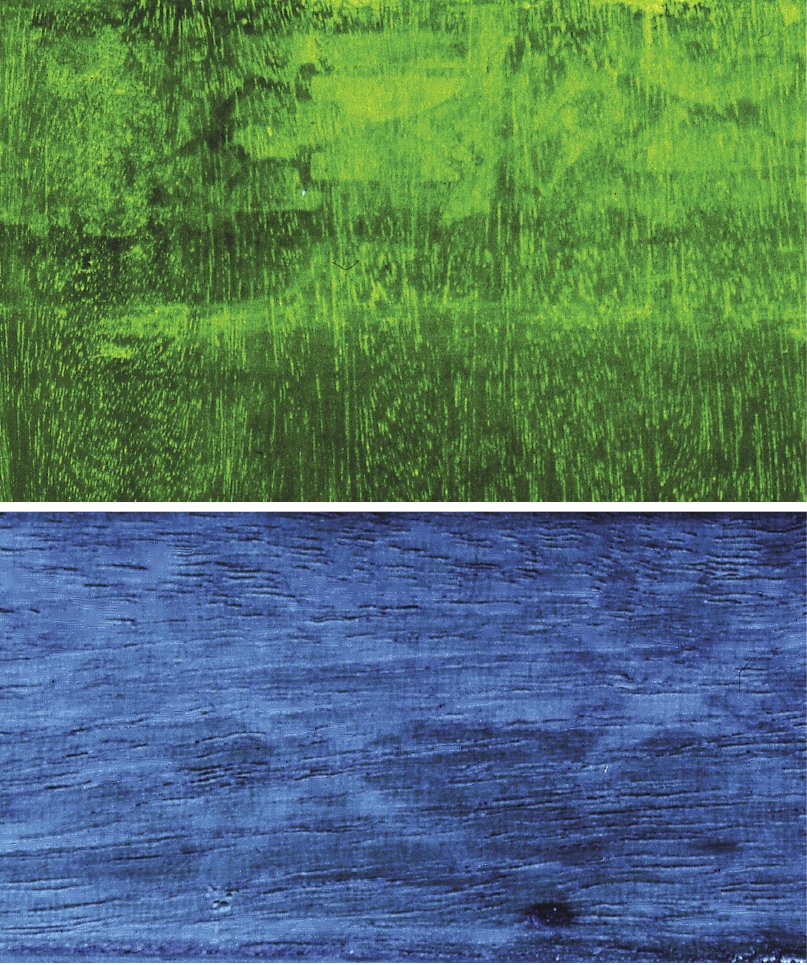

Details of the upper and lower case fret locations. These two 35 mm transparencies made in 1975 reveal witness marks from the original fret pattern. This type of applied fret is easily damaged. It is possible that after sustaining a certain amount of damage, a previous owner completely removed the fret rather than attempt a restoration. The discovery of the visual records was of enormous value as they contained the information needed to re-create the fret for the high chest without having to speculate about the original pattern design; any trace of these patterns had been lost during subsequent refinishing. The information in the slides allowed for the reconstruction of the fret across both the facades and sides. The exact placement of the fret on the chest could be determined by matching the wood grain pattern seen in the slides with the grain on the case. The diamond motif of both the upper and lower fret designs lines up over the diamond motif of the pierced brass escutcheons on the drawer fronts. This demonstrates particular attention to detail on behalf of the cabinetmaker. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. |

Although the Philadelphia Museum of Art did not formally acquire the high chest until 1957, when it was given by Mrs. Henry V. Greenough (Amanda Howe Steel), it has been exhibited at the museum at various times since 1924. In that year it was loaned to the museum by the estate of Mary Fell Howe for an exhibit on furniture in the “Chippendale Style.” The high chest was featured prominently in the frontispiece of the May 1924 edition of The Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin, a large portion of which was devoted to the loan exhibit. The two-fold purpose of the exhibition was “…to present an important group of objects that shall exemplify in the best possible manner the preeminent merits of this period of furniture design, as well to illustrate the expression of this style in America and direct attention particularly to the proficiency of the Philadelphia cabinet-makers who flourished during the eighteenth century.” It was a landmark exhibition of Philadelphia furniture, and coincided with the opening of the American Wing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 2007, furniture conservators at the museum carried out a complex conservation treatment and restoration of the high chest. Modern institutional conservation practice combines a thorough examination and documentation of the current condition and physical history of an object with extensive historical research. The results produce a detailed conservation treatment plan that is eventually agreed upon by a team of curators and conservators.

It was determined that poorly executed previous restorati ons and missing carved elements had significantly changed the maker’s original design and intent. Additionally, a deteriorating modern nitro-cellulose lacquer coating was obscuring the dramatically grained mahogany used for the drawer fronts. Collectively the effect was detrimental to the interpretation of the high chest as an historic object and made appreciation of the high chest’s exceptional artistic merits problematic.5 The treatment that was ultimately approved and carried out included the replacement of all the repairs previously made to the carving and fret during two prior restoration campaigns; the restoration of long missing carved elements; the careful removal of the modern lacquer finish; and the application of a more sympathetic and appropriate shellac coating.

The captions and images provided here focus on specific details as to the work that was undertaken to conserve this important object and prepare it for proper interpretation as to its original appearance.

1. Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Table’s Tale: Craft, Art, and Opportunity in Eighteenth Century Philadelphia” in American Furniture, ed. Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004).

2. Beatrice Garvan, “Pennsylvania Hospital,” in Philadelphia: Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), 64.

3. The Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Vol. 1, 1784–1804, eds. John C. van Horne and Lee W. Formwalt (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984). Unfortunately neither the stove nor Latrobe’s drawings for it survive.

4. The observation that Jugiez derived his design from the Johnson plate was first made by David W. Kiehl in his unpublished manuscript, Aesopic Carving in Philadelphia, 1971. See curatorial object file 1957–129–1 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

5. See Lita Solis-Cohen, “Changing Ideas about Museum Restorations,” in The Philadelphia Inquirer, July 18, 1976, for a discussion of a 1975 treatment. Also, Philip D. Zimmerman, “Truth or Consequences: Restoration of Winterthur’s Van Pelt High Chest,” in Winterthur Portfolio 33, No. 1. The article is a case study of the analysis and treatment of a similar object.

Christopher Storb is project conservator for furniture and woodwork at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2008 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|