|

|

|

|

|

Compiled by Charles Burden and Ray Egan

|

|

|

Maine is credited with being the birthplace of American folk art collecting, initiated in 1913 by New York painter and art critic Hamilton Easter Field (1873–1922), when he established an art school in the thriving art colony in Ogunquit, Maine. To house students and artists in residence he purchased several cottages and fishermen’s shacks in Ogunquit and nearby Cape Neddick and furnished them with hooked rugs, decoys, paintings, and early American chairs and tables found in the area. Among those exposed to the material were prominent artists of the day, including Marsden Hartley, Robert Laurent, and Bernard Karfiol. Taking their lead from Field, both Karfiol and Laurent began to collect folk art, as did other modernist artists. Some lent pieces to the first exhibition of American folk art at the Whitney Studio Club in New York in 1924.

Following Field’s death in 1922, Robert Laurent continued to operate the Ogunquit school. In 1925, the painter Sam Halpert stayed in one of the Perkins Cove cottages. His wife, New York art dealer Edith Gregor Halpert, who returned with him the following year, declared Hamilton Field the undeniable 'pioneer in the field' of folk art collecting, crediting him with being 'responsible for directing attention to American folk art as an aesthetic expression.' During their stay in Maine, the Halperts welcomed as their guest Holger Cahill of the Newark Museum in Newark, Delaware. This resulted in Cahill’s 1930 opening of the first exhibit of American folk art in a major museum, to which Laurent was the largest contributor. Laurent’s holdings also fed other exhibitions and collections, including that of Mrs. John D. Rockefeller Jr. and her Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Long before it became known as 'folk art,' older Maine historical societies had been acquiring the craft of tradesmen, schoolgirls, sailors, and other untrained artisans solely for their importance to the cultural history of the state. Some of the decoys, birth records, sea chests, and furniture collected before 1930 are today considered among the best examples of American folk art in existence. Since then, hundreds of pieces have entered the collections of Maine museums for both their historical and/or folk art qualities. Eighty-five years after hosting the birth of folk art appreciation, Maine is again the site of a milestone in American folk art history. This summer continuing into fall, eleven major museums located along what is being called the Maine Folk Art Trail, stretching from York to Waterville and Searsport, will simultaneously exhibit their folk art collections, which consist of objects made in Maine as well as from outside the state.

To round out the festival, an all day symposium at Bates College, Lewiston, on 28 September, will feature experts on paint decorated furniture, hooked rugs, quilts, schoolgirl art, scrimshaw, itinerant portrait painters, glazed decorated red ware, and Shaker folk art. For more information visit www.mainefolkarttrail.org.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carved wooden bird weathervane, by James Lombard (no dates), southern Maine, ca. 1900. Pine. H. 19H, W. 26H in. Courtesy of Rufus Porter Museum, anonymous loan.

|

This wooden weathervane, carved in the form of a rooster, is attributed to James Lombard, farmer and cabinetmaker from Bridgton and Brownfield, Maine. Roosters and hens were favorite motifs for weathervanes from the late eighteenth century onward, and are the only forms Lombard is known to have produced. Being of rather perishable materials, they often suffered from the adverse effects of the weather; this one is reinforced with an old iron support of later date. Lombard’s weathervanes are recognizable by their bold, stylized, flat designs. His weathervanes are in the Rufus Porter Museum and the Bridgton Historical Society, both in Bridgton, Maine, and in the Shelburne Museum in Vermont.

Boxes were commonly used from the late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries either for additional household storage or for travel. Ranging from a few inches to as much as four feet in size,

|

|

|

|

|

Birch bark decorated dome top box, maker unknown, ca. 1820. Pine. H. 5K, W. 11, D. 5I in. Courtesy of Bates College Museum of Art, Deborah N. Isaacson Trust Collection.

|

some were produced in shops, a lesser number were homemade. This box, painted to look like birch bark, is one of two known examples whose decoration alludes to the use of this material

by Indians of the region; the other is in a private collection.

The whaleship Emerald depicted on this tooth was built in Boston in 1822 and spent most of her life working out of New Bedford. Pettegrow, who inscribed his name on the reverse, was likely a sailor aboard the ship and, like many aboard whaleships, passed his dormant hours at sea creating decorative objects out of byproducts of the whale hunt. Most scrimshaw in Maine museums

probably has no connection to the state. There are quite a few pieces known to have been created by sailors from Maine, but only four pieces are known to have been made aboard whaleships from Maine.

|

|

|

BOTTOM LEFT: Scrimshawed whale tooth, by Pettegrow (no dates), ca. 1850. Whale ivory. H. 5M in. Courtesy of Penobscot Marine Museum; anonymous gift.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Dressing table signed by Madison Tuck (1809–1894), ca. 1830–1840. White pine with basswood and brass.

H. 38, W. 33, D. 17 in. Courtesy of Maine State Museum; gift of Sam Pennington.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carved fiddle head by Eliphalet Grover (1778–1855), 1821. The fiddle is 25H x 8 x 1I in. Courtesy of Museums of Old York; gift of Reverend Frank Sewall.

|

Eliphalet Grover was the lighthouse keeper on Boon Island, located off the coast of York, Maine. Materials were scarce on the rocky island and he utilized the scant materials available to him, employing split wood shingles to make the top and back of the fiddle. A small wooden inlaid box by Grover is also in the museum.

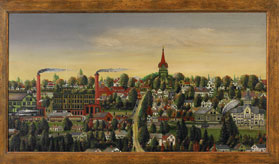

George J. Griffen, a Freeport house painter, was capitalizing on the interest in depictions of towns and villages at the time. Such images were also captured in the lithographic bird’s-eye views of hundreds of towns in the late 1800s that were printed in large runs to make them affordable. These depictions document how profoundly industrialization and urbanization had changed the landscape in the prior fifty years.

The artist, a captain who commanded vessels of this size and type, shows the bright colors in which ships’ hulls were painted at that period. Rittall depicts the original lighthouse on Seguin Island, at the mouth of the Kennebec River in Maine. The American flag depicts the inclusion of the seventeenth state, Ohio, with an additional stripe and star added in 1803. Note the decorative styling of German Fraktur art around the borders. Rittall was of German descent, as were many settlers in his Dresden, Maine, hometown.

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT: G. J. Griffen (no dates), View of Freeport, Maine, 1886. Oil on canvas, 21 x 38G inches. Courtesy of Colby College Museum of Art; purchase with Jere Abbott Fund.

RIGHT: Capt. Francis Rittall (1764–1819), Ship Lady Washington, 1803. Watercolor on paper, 20H x 28H inches. Courtesy of Maine Maritime Museum; gift of C. L. Groves and G. E. Castner.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Brewster Jr. (1766–1854), Mary Warren Bryant, ca. 1815–1820. Oil on canvas, 58H x 25G inches. Courtesy of Saco Museum; gift of Albert Smith.

|

Deaf itinerant portrait painter John Brewster Jr. was commissioned to paint portraits of many individuals throughout New England and New York. His work is characterized by a flatness, evident in the faces and bodies, strong contrasts between light and dark tones, and emphasis on brightly colored objects. Although nothing about Mrs. Bryant in this portrait suggests that she was a swinger, her husband was an active follower of the radical religious sect known as 'Cochranism,' founded by Jacob Cochrane (1782–1836), who preached a kind of free love for which they coined the term 'spiritual wifery.' The sect existed from 1816 to 1819, when the charismatic preacher was imprisoned for 'gross lewd and lascivious conduct.' This portrait was painted around the time of the sect’s activity.

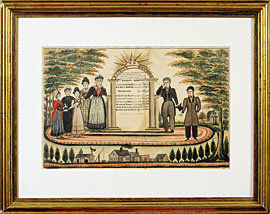

This register records the major events in the lives of Samuel and Lydia Libby of Scarborough, Maine. While many registers recording family members’ birth dates have survived, few have such carefully rendered homestead and outbuildings around the borders as does this one. The artist, James Osborne, was an itinerant painter working in Maine at the time.

Adelaide Endora Smith (1849–1921) was three years old when she posed for the artist, Sturtevant Hamblen. Hamblen and his brothers, Eli, Joseph, and Nathaniel, who were also artists, traveled extensively in Maine during the 1830s and early ‘40s in search of commissions. The brothers all painted in a similar manner, but this portrait is attributed to Sturtevant on the basis of stylistic similarities to other portraits known to have been painted by him. Rosamond, a sister of the brothers, was married to another well-known painter of the period, William Matthew Prior. The sitter, Adelaide, married Frederick E. Booth in 1871. Booth became mayor of Portland, Maine, in 1901, and in 1916, mayor of Waterville.

|

|

|

|

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: James Osborne (no dates), Libby family register, Scarborough, Me., ca. 1830. Watercolor on paper, 16 x 23H inches. Courtesy of Maine Historical Society; gift of Dorothy Plummer.

Sturtevant Hamblen (1817–1884), Adelaide Endora Smith, Waterville, Me., 1852. Oil on canvas, 38 x 28I inches.Courtesy of Colby College Museum of Art; gift of Mr. and Mrs. George Putnam.

Carved firehouse eagle plaque, by Nahum Littlefield, Portland, Me., ca. 1874. Wood. H. 3, W. 9 feet. Courtesy of Saco Museum; Portland Fire Museum loan.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A. Ellis (no dates), attributed, Portrait of a Boy and Dog, ca. 1835. Oil on wood panel, 42 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Maine State Museum; gift of A. M. and W. L. McPhredran.

|

|

|

Littlefield was active as a ship carver in Portland from about 1850 until 1880, creating figureheads, cabin carvings, and such, for ship owners. He was also a member of the Portland volunteer fire department and served as its chief in the 1880s. He carved this eagle-decorated sign for the Hook and Ladder Company on India Street in Portland, for which he was paid $34 by the city.

This is one of fewer than than twenty portraits by the same hand. It is attributed to A. Ellis, based on a signed painting at the New York Historical Association in Cooperstown, New York. Most of Ellis’s sitters lived in central Maine or New Hampshire. All share the same treatment of the eyes and nose; showing the nose as a continuation of an eyebrow.

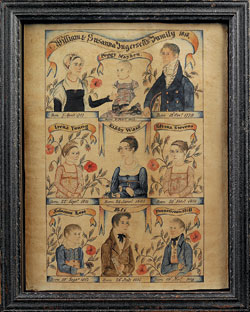

This document records the images of William and Susanna Ingersell of Columbia, Maine, and their seven children who were living at that date. (Note the children’s surnames have been misspelled.) This family record is unusual in that it depicts the people being celebrated, usually only mentioned by name. By 1833, the Ingersells had produced eight more children.

Institutions Participating in Maine’s Folk Art Trail

(in order of exhibit opening dates):

through November 2 Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland

through September 29 Saco Museum, Saco

May 23 – October 6 Sabbath Day Lake Shaker Museum,

New Gloucester

May 24 – October 13 Maine Maritime Museum, Bath

June 3 – October 15 Rufus Porter Museum, Bridgton

June 5 – December 14 Bates College Museum of Art,

Lewiston

June 7 – October 11 Museums of Old York, York

|

|

|

|

|

Ingersell family record, maker unknown, 1818. Ink and watercolor on paper, 18H x 16H inches. Courtesy of Rufus Porter Museum; anonymous loan.

|

June 12 – October 19 Penobscot Marine Museum,

Searsport

June 27 – December 30 Maine Historical Society,

Portland

June 28 – October 12 Maine State Museum, Augusta

June 29 – October 19 Colby College Museum of Art,

Waterville

|

|

|

|

|

|

Charles E. Burden is a founder of the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath; he has also contributed collections to other regional institutions. He is an avid collector of Maine-related nautical memorabilia and is co-director of the Maine Folk Art Trail. Ray Egan has been a collector of American folk art for over forty years and is director for the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens. He is co-director of the Maine Folk Art Trail.

|

|

|

|