|

| Home | Articles | To Please Any Taste: Litchfield County Furniture and Furniture Makers, 1780-1830 |

|

|

by Julie Frey

|

|

|

|

|

|

Map of Litchfield County. Warren and Gillet map of Conncticut, 1811. Courtesy of the National Archives, College Park, Md.

|

In 1969 the Litchfield Historical Society published a catalogue to accompany their latest exhibition on Litchfield County furniture. This publication represented a radical new approach to furniture study, grouping pieces not by an individual maker but by a specific region. The following decades saw a marked increase in regional furniture studies throughout Connecticut and greater New England. After almost forty years and much subsequent scholarship, the Historical Society revisits this topic in To Please Any Taste: Litchfield County Furniture and Furniture Makers, 1780-1830. While discussing the style, construction techniques, and regional characteristics of pieces attributed to the county, the exhibit also focuses on interpreting the furniture and its makers as a reflection of the rapid economic and social changes in the region during this pivotal fifty-year period.

Litchfield County was the last area settled in the state of Connecticut. Land speculators developed many of the county's larger communities of Litchfield (in 1721), Woodbury (in 1673), and New Milford (in 1712). The remaining lands of the county were then clustered into regional parcels by the state's legislative body, the General Assembly, and sold at auction in 1737. Many long established and multi-generational families in surrounding Fairfield, Hartford, and New London counties welcomed this opportunity to procure additional farmlands for younger generations and participate in the new political and social power structure being developed in these new communities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

John Warner Barbor print of Litchfield, Connecticut, 1836. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

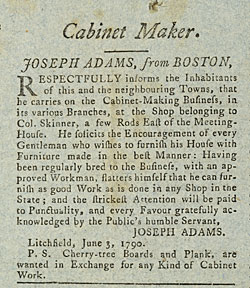

Joseph Adams advertisement in the Litchfield Monitor (June 14, 1790), Vol. V, issue 259, p. 4. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society.

|

Within a generation, the county was transformed from wilderness into a lively region of commercial and civic prosperity. Sixty families moved from Colchester and Lebanon in New London County to Sharon in the northwest corner of Litchfield County within the first two years of settlement. These families brought with them strong community ties, established social mores, and decided tastes. Woodbury, in the southeast, became a center for agricultural production, while New Milford, in the southwest corner of the county, became a commercial port on the Housatonic River, exporting resources from the interior of the county in exchange for goods from New York and southern Connecticut. The town of Litchfield, located in the lower quardrant of the northeast corner, became the center of transportation, commerce, and civic life after it was named the county seat in 1751, and subsequently developed strong trading ties with New York City, Boston, London, and the Far East. A tax-roster from Litchfield in the 1780s showed a population of growing occupational diversity that included attorneys, physicians, merchants, tailors, a goldsmith, a clockmaker, a silversmith, joiners, blacksmiths, and no fewer than eighteen tavern keepers. Litchfield also gained national recognition as the home of the Litchfield Law School and the Litchfield Female Academy, two pioneering institutions of education founded in 1774 and 1792, respectively.

Sharon, Salisbury, Canaan, and Kent in the northwest grew dramatically after iron was discovered in the region in 1732. In the early nineteenth century, the nation's lucrative ironworks were concentrated here, with five furnaces, thirty forges, three anchor chops, and two slitting mills. As an example of the level of industry, according to an 1812 estimate: Kent's six iron forges brought $20,000 to $30,000 into the town annually.

Litchfield County is unique and complex because each corner of the county produced furniture with distinctive characteristics, both in terms of construction techniques and outward appearance. The citizens of this expanding county expected their homes, clothing, and furnishings to reflect their growing status and aspirations, and the craftsmen who prospered found a way to cater to the needs of the diverse and newly integrated population. The furniture produced from the more than 700 craftsmen discovered as working in the county between 1780 and 1830 displays distinctive regional styles created through a combination of each community's aesthetic preferences blended with a particular craftsman's style, training, and construction techniques.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Woodbury chest on chest, ca. 1790. Courtesy of a private collection.

|

For example, in the southeast corner around Woodbury, where the agricultural-based economy adhered to a slower pace of change, the Chippendale style lasted into the turn of the nineteenth century. Two of the most noticeable features found in furniture produced in this area are a drawer front with a deeply carved shell, and what is known as the Woodbury carved foot. The shell was often so deeply carved, a second block of wood was placed behind the drawer front to accommodate the carving. The Woodbury carved foot is often misidentified as a 'Spanish' foot, but it has deeper and more defined carving, as well as an overall squat or square appearance.

Contrary to this, the furniture made in the towns of Sharon, Salisbury, Kent, and Canaan in the northwestern corner of the county often has serpentine fronts, decorative gadrooning, and ball and claw feet similar to furniture made in the southern Connecticut county of New London, where many of the residents of this northwest corner originated. The iron industry in this region also allowed craftsmen to use iron nails and hardware instead of dovetailed joints when constructing furniture.

New research has provided a fuller picture of two illusive craftsmen known to have worked in this region. Previously, signed pieces existed for Reuben Beaman Jr. (1772-1814) and Bates How (1776-1801) but little was known about their individual careers. In addition to learning their birth and death dates, the most startling discovery is that the majority of their careers were spent in shops in New Marlborough, Massachusetts, just across the border from Canaan, Connecticut. Scholars had previously placed the two furniture makers in Kent, Connecticut. Reuben Beman Jr. was trained by his father, Reuben Beman, who migrated to Kent, Connecticut, from New London County, before moving his family to New Marlborough. How is thought to have trained in Beman's New Marlborough shop with Beman Jr. Additional signed pieces by each maker, discovered since 1969 and currently in private collections, are on display in the exhibition.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Woodbury chest of drawers, ca. 1790. Collection of Hartford Steam Boiler, an AIG Company.

|

|

The northeast region of Litchfield County, where the towns of Litchfield, Torrington, New Hartford, and Colebrook are located, developed a unique design identity slightly later than the other regions. Although Litchfield was named the county seat in 1751, it did not fully prosper until after the Revolutionary War, when local citizens such as Julius Deming, Col. Benjamin Tallmadge, and Oliver Wolcott Jr. gained notoriety and success from their wartime endeavors. With business savvy, these men turned their name recognition into several successful business ventures that brought tremendous wealth to the community. They, as well as other Litchfield residents, expected their home furnishings to reflect their status in the community. The account books of local furniture maker Silas Cheney (1776-1821) show the production of such high-end furniture forms as sideboards, tea tables, washstands, and side chairs.

|

|

|

Woodbury chest of drawers, detail of foot. Collection of Hartford Steam Boiler, an AIG Company.

|

Cheney and other profitable furniture makers in this community excelled in the Federal and early Empire styles of furniture. Their clients, such as Deming and Wolcott, traveled to New York and Boston and were familiar with the latest styles being produced in these urban areas. Cheney responded by producing tables, sideboards, chests, and desks with the delicate inlay that reflected the current tastes.

The most significant post-1969 discovery from Litchfield County is the identification and documentation of case pieces with the unique construction feature of cross bracing (Figs. 10 and 10a). This construction technique is unique to this region. Comprised of two braces fastened at an angle to the inside of the foot with a shallow tenon and reinforced with a wooden peg, the braces provide support for the case piece and reinforcement for the feet. Previously only a handful of examples had surfaced with this unique characteristic; to date, twenty examples have been discovered and documented. In addition, patterns and construction idiosyncrasies have enabled the pieces to be clustered into three distinct groups. While none of the known examples are signed, the hope remains that a signed piece will surface and reveal further information on this unique construction technique.

|

|

|

|

|

Sideboard by Silas Cheney, made for Tapping Reeve of Litchfield, Connecticut, 1800. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Detail of chest of drawers showing underside of chest where screws were used by How. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.

|

|

|

Chest of drawers, inscribed 'This Buro was made in the Year of our Lord 1795 By Bates How.' Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection.

|

The final region of the county, New Milford is the the southwest corner, exhibits a more flamboyant style. This was the result of its vibrant trading economy and southern location, which gave it closer proximity and connections to the fashions of the urban hub of New York City. Chests of drawers, dressing tables, high chests, and desks show carved shells or inlay on drawers and surfaces. Punch carved decoration on knees and along shell scallops are also featured design elements. Newer and fancier furniture such as tea chests and card tables also appear earlier in the inventories of this community.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Side chair by Silas Cheney, Litchfield, made for Tapping Reeve, ca. 1800. One of a set of ten side chairs, two armchairs, and a settee. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society. The design of this chair is very similar to examples from New York.

|

For fifty years, individual furniture makers and small shops flourished in Litchfield County, catering to the needs of their customers and creating pieces that reflected the aesthetics of their community. By the 1830s, however, the world had begun to change. New transportation networks and updated methods of production enabled furniture to be made faster and sold on a national scale. Some adapted to the changing economy. George Dewey, for example, began to import furniture from New York to his Litchfield shop to resell to local clients. Lambert Hitchcock, a furniture maker who apprenticed under Silas Cheney in Litchfield, went on to open a furniture factory in present-day Barkhamstad. Other factories, opening up and down the Naugatuck River during the 1830s and 1840s, irrevocably changed the way furniture was made and sold in Litchfield County. In only fifty years the world of Litchfield County residents had shifted dramatically from a regionally focused economy to a national and even global market.

|

|

New Milford dressing table, ca. 1790. Courtesy of a private collection.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Desk, Litchfield, Connecticut, possibly made for John Woodruff or his son Morris Woodruff, ca. 1790. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Underside of desk showing cross bracing. Courtesy of the Litchfield Historical Society.

|

|

|

|

To Please Any Taste: Litchfield County Furniture and Furniture Makers, 1780-1830 runs through November 30, 2008. Over thirty examples of Litchfield County furniture are included in the exhibition. In addition to pieces from the Litchfield Historical Society's collection, furniture from the Yale University Art Museum, Connecticut Historical Society, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Connecticut Landmarks, Hartford Steam Boiler Insurance, an AIG Company, Torrington Historical Society, Salisbury Association, Winterthur Museum, as well as numerous private lenders, are showcased. An exhibition catalogue accompanies the exhibit and a CD database featuring descriptions and photographs of over three hundred identified examples is available for purchase. Please call the Litchfield Historical Society at 860.567.4501, or visit the website at www.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org for more information.

|

|

|

Julie Frey is curator of collections of the Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, Connecticut.

|

|

|

|