|

| Home | Articles | To the Ends of the Earth: Painting the Polar Landscape |

)

|

|

by Samuel Scott

|

The polar landscape painting tradition in Western art belongs most appropriately to a period of one hundred years that begins in the 1830s and ends in the 1930s. The exploring expeditions of the eighteenth century introduced Western consciousness to the Arctic and the Antarctic, whetting the popular appetite for all things polar. For earlier generations, the North Pole was varyingly imagined as a region of the gods, a middle ground between life and death, and a hostile land where immutable natural forces challenged mankind's hubris. When the existence of a corresponding ice cap in the Southern hemisphere was established by the late-eighteenth-century voyages of Captain James Cook and others, it inherited these mythic associations, until nineteenth-century explorers and artists, inspired to make the arduous journey to these remote locales, tested and reshaped these images of polar space.

The concept of polar space as the site of heroic endeavor was fertile ground for landscape painters. They carefully composed the awesome power of the environment into a setting against which the presence of the cultural hero is projected. The landscape becomes set design and the ship – or occasionally other types of human constructions – the actor. The ship was a useful visual symbol because it represented not only a real physical object, but was culturally understood to embody the accomplishments of its commander, the cooperative effort of its crew, and by extension the cultural ambition of its country of origin. The polar regions were also a site of spiritual pilgrimage, where the elemental hand of God in the world was exposed.

In the nineteenth century, the value placed by science on personal observation was increasingly echoed by the emerging notion among landscape painters that their work should be done from nature. Thomas Cole and the Hudson River School were among the first American painters to receive critical acclaim for working in this mode. Frederic Church, especially, showed that what was artistically appropriate for the landscape within an easy journey from New York City also applied to the icy high latitudes of the Davis Strait. Artists increasingly joined scientific missions and officially sanctioned exploration to paint awe-inspiring landscapes.

The imaging of the polar environment resonated with both the Romantic and early modernist traditions of landscape painting. For artists like William Bradford and Frederic Edwin Church, who were striving to capture the sublime, the poles delivered epic natural forces against which to set the frailty of human existence. A nearly geometric reduction of a grand scene to its elemental qualities was typical of early modernists Rockwell Kent and Lawren Harris, who excelled in conveying the nature of the polar environments through their graphic attributes. For painters seeking new ways of seeing through painting, the polar landscape provided an austerity of space, purity of light, and an architectural setting well suited to their objectives.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frederic Edwin Church (American,1826–1900), Aurora Borealis, 1865. Oil on canvas. 56 x 83-1/2 inches. Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Eleanor Blodgett, 1911.4.1.

|

|

|

Church's mastery of the representation of light gives this picture a quiet sublimity rare in depictions of the Arctic. The aurora commands the sky and infuses the frozen planes of ice and snow with an otherworldly glow. Church works with the distant ice, far-distant mountains, and the impossibly distant celestial phenomenon of the aurora itself. The key to the success of these grandly scaled elements is Church's inclusion of the American exploring schooner United States, commanded by Church's friend Isaac Israel Hayes, set in the pack ice at lower left. The vessel, reduced to insignificance by the surrounding environment, is what allows the viewer to appreciate the truly staggering scale of the scene depicted. Church composed the painting from his own experiences on the coast of Labrador in 1859, combined with Hayes's accounts and sketches.

|

|

|

|

|

|

George Marston (British, 1850–1946), Aurora Australis, 1908. Oil on canvas, 26 x 31 inches. Courtesy of a private collection.

|

|

|

Marston rendered the aurora in simple, layered, vertical brushstrokes, creating an affect that corroborates first-hand written accounts of the phenomenon. This is not surprising as Marston's painting was executed on site–inside the hut at Cape Boyds shown in the work–when he accompanied Earnest Shackleton on the Nimrod Expedition of 1907–1909. Marston was also on Shackleton's ill-fated Endurance Expedition of 1914–1916.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Admiral William Smyth (British, 1800–1877), Perilous Position of HMS Terror, Captain Back, in the Arctic Regions in the Summer of 1837, after 1840. Oil on canvas, 39-1/2 x 55-1/2 inches. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

|

|

|

Smith utilizes dramatic environmental effects with special attention paid to the depiction of the ice, which in this picture embodies the overwhelming forces of nature. Like other polar artists he was not shy about exaggerating the icy elements in his paintings. He sets the Terror in a jagged nest of broken ice, eerily lit with alternating light and shadow, evoking the frozen underworld of Dante's ninth circle of Hell. A member of Captain George Back's Northwest Passage expedition that set out in 1836, Smyth was senior lieutenant of the Terror.

|

|

|

|

|

Attributed to Charles Wilkes (American, 1798–1877), USS Vincennes in Disappointment Bay, after 1842. Oil on canvas, 23-1/2 x 35-1/2 inches. Peabody Essex Museum, Museum Purchase, 1902, M265.

|

|

|

|

This painting shows the flagship of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 off the coast of Antarctica in January 1840, at the furthest point south that any of the vessels on that expedition reached. The vessel appears to sit serenely in an icy setting, surrounded by charming, if somewhat inexpertly rendered, local fauna. However, navigation among sea ice in a large sailing vessel with no engine was one of the most challenging and dangerous feats of seafaring. That this operation was accomplished successfully and without mishap was a tribute to the skills of the vessel's crew and its commander, Captain Charles Wilkes, to whom the painting is attributed.

|

|

|

|

William Bradford (American, 1823–1892), Sealers Crushed by Icebergs, 1866. Oil on canvas. 79 x 126 inches. Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum, 1972.33.

|

|

William Bradford's monumental work established his position as the preeminent American painter of the Arctic. Sealers presents a sweeping panorama of the overwhelming power of the Arctic environment and the frailty of such objects of human ingenuity as ocean-going vessels. The size of the canvas allows the picture itself to mimic the relationship between man and nature, which is the subject of the painting.

|

|

|

|

|

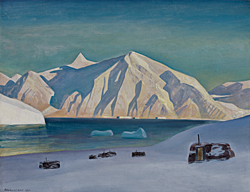

Rockwell Kent (American, 1882–1971), First Snow, Greenland, 1931. Oil on canvas, 43 x 53. Courtesy of a private collection.

|

|

|

|

Rockwell Kent's depictions of the polar environment were deeply personal. He traveled to Alaska in 1919 and to Greenland in the 1930s, and wrote about his experiences in these places, referring to the latter as his 'eternal fountainhead of all that is beautiful in art and man, the virgin universe.'1 On his Greenland trip, Kent achieved a glowing luminosity unparalleled in any of his other paintings. First Snow, Greenland deftly juxtaposes the rich darkness of the sky with the ethereal light of the sunlit snow and ice.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lawren S. Harris (Canadian,1885–1970), Icebergs, Davis Strait, 1930. Oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches. Courtesy of McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario; gift of Mr. and Mrs. H. Spencer Clark, 1971.17.

|

|

|

Harris was a founding member of the Group of Seven artists, who were attempting to forge an original &'Canadian' style of visualizing their own land. With an affinity for painting rugged, remote landscapes, Harris found all he could hope for in the Canadian wilderness that stretched to the Arctic Circle and beyond. In 1930, Harris joined his Group of Seven compatriot A. Y. Jackson aboard the RCMP steamer Beothic on its tour of communities and settlements in the Canadian Arctic. Icebergs, Davis Straits shares many of the characteristics of clean line and rich color of fellow modernist Rockwell Kent's Greenland paintings, but taken by Harris to an even more idealized degree.

|

|

|

The exhibition To the Ends of the Earth: Painting the Polar Landscape features more than fifty works depicting the drama and magnificence of the Arctic and Antarctic regions. It is on view at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, from November 8, 2008 through March 1, 2009. An exhibition catalogue by the same title is available. For more information call 978.745.9500 or visit www.pem.org.

1. Rockwell Kent, Salamina (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1935), 24.

|

|

|

Samuel Scott is the associate curator of the Russell W. Knight Department of Maritime Art and History at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem Massachusetts.

|

|

|