A Ceremonial Desk by Robert Walker, Virginia Cabinetmaker by Sumpter Priddy

|

| Fig. 1: Desk, attributed to the shop of Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia ca. 1750. Walnut primary; yellow pine secondary. H. 44, W. 43-1/2, D. 23-1/2 in. The desk originally had a bookcase, which is now missing. |

by Sumpter Priddy

| |

| Fig. 1a: Detail of the prospect door of figure 1. |

This commanding desk is among the most significant discoveries in Southern furniture to come to light in recent decades.1 The desk's remarkable iconography — including hairy paw feet, knees carved with lions' heads, and the bust of a Roman statesman raised in relief on its prospect door — is rare in colonial America (Figs. 1–1b). Two of these elements appear in tandem on only one other piece of colonial furniture, a ceremonial armchair used by Virginia's Royal Governors at the Capitol in Williamsburg (Fig. 2).2 Not surprisingly, an intriguing trail of evidence suggests that this desk was owned by Virginia's Royal Governor Thomas Lee (ca. 1690–1750), the master of Stratford, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, and kinsman of Robert E. Lee, the celebrated general of the Confederate forces during the American Civil War.

The desk is attributed with certainty to the Scottish émigré cabinetmaker Robert Walker (1710–1777) of King George County, Virginia. Robert and his older brother, William (ca.1705–1750), a talented house joiner, found themselves in great demand among the wealthiest families in the colony and often worked in tandem building and furnishing houses. Extensive research undertaken by Robert Leath, Director of Collections for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, has uncovered strong documentary evidence related to the Walkers, their patrons, and their furniture, and has effected a re-evaluation of baroque and rococo style in the early Chesapeake.3 Indeed, documented pieces by the Walkers, together with new insights into the 1740s pattern book designs available to the brothers and their patrons, indicate that this desk originated around 1750 or slightly earlier.

| |

| Fig. 1b: Detail of one of the legs of figure 1. |

Students of American furniture have traditionally associated the decorative features as seen on this desk with rococo designs credited to Thomas Chippendale's Gentleman and Cabinetmaker's Director (London, 1754). Yet, many of the details promoted by and assigned to Chippendale actually emerged in earlier baroque design sources — and on aristocratic British furniture — long before the 1750s. For example, the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans employed lions' paw feet with some frequency, and continental designers revived their use during the Renaissance. By the late 1720s — and possibly earlier — London's pre-eminent furniture designer, Giles Grendey (1693–1780), chose paw feet for his most fashionable cabinets-on-stands and caned chairs; concurrent options were smooth paw feet or claw-and-ball feet. John Gloag, in A Short Dictionary of Furniture, and Brock Jobe, in Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast, both illustrate circa 1735 British hairy paw feet.4 The latter are on an altar table made for St. Clare's Rye Church in London; it, like the Walker desk, also features carved masks on the knees.

Such combinations do not reflect a rococo aesthetic, but rather, a baroque one, widely credited to architect and furniture designer William Kent (1685–1748) early in the second quarter of the eighteenth century.5 Additionally, paw feet were familiar in the Walkers' native Scotland during the 1730s, when they appeared on Edinburgh cabinetmaker Francis Brodie's (w. 1725–1779) engraved trade card, and were subsequently employed by Brodie's Edinburgh contemporary, Alexander Peter (w. 1728–1764), who offered for sale furnishings having "Carved feet with Lyons claw."6

|

| Fig. 2: Ceremonial armchair, circa 1750, Williamsburg, Virginia, or London, England. Mahogany primary; beech secondary. Stool is a reproduction. H. 49, W. 21-1/2, SD. 24-1/2 in. Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1930.215. |

The Walker family was situated near the epicenter of Scottish design during the 1720s and 1730s, in a context where baroque details were well known to aristocratic Scottish patrons. As Robert Leath has demonstrated, their father, William Walker the elder (d. 1710), served as "Joyner to her Grace the Duchess of Buccleugh [sic]" and his interiors for her home, Dalkeith, brought him into close contact with the most accomplished artisans of the realm. The Duchess sent Walker to London to survey the most stylish staircases and meet with the Royal cabinetmaker James Moore, suggesting communication between Scotland's most talented artisans and those in progressive London.7

Although his early life and training in Scotland are at this time unknown, Robert Walker's American furniture indicates that he, like his father, had extensive knowledge of advanced British design before immigrating to Virginia, and possessed a sense of style unparalleled among his colonial counterparts. Identifying the specific sources that influenced such progressive émigré cabinetmakers is often difficult; even the most highly regarded design books of the era often borrowed freely from earlier works.

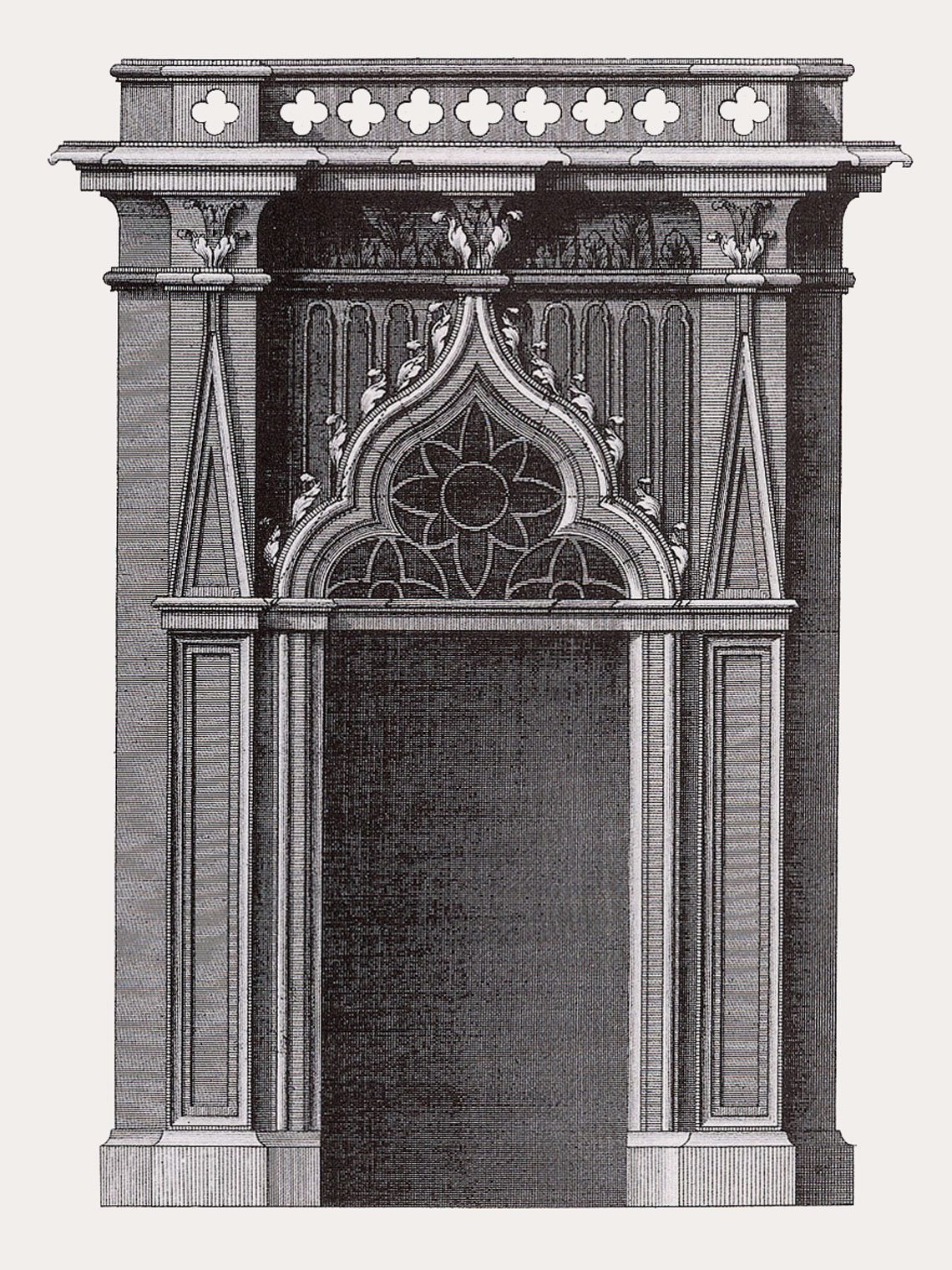

A survey of period sources suggests that Walker likely adapted designs from Batty Langley (1696–1751), whose publications exerted a tremendous influence on European and colonial artisans in the second quarter of the eighteenth century. Langley's The Builder's Chest-Book was published in London in 1727. Over the next fifteen years, he would strengthen his reputation as a designer by producing another ten books, the most influential (and controversial at the time) being the seminal Ancient Architecture Restored, and Improved(London, 1742). This particular volume is of great interest as it includes Langley's first interpretation of the Gothic order. Plate XXIV contains a Gothic arch closely related to the one found on the prospect door of this desk (Fig. 3). In 1746, Langley updated the design as "Gothick Arches for Heads of Chimney Pieces etc." and published it as plate 168 in his The Builder's Director or, Bench-Mate. Also, appearing as plate 182 in this publication, was an illustration of a Gothic arch that depicts a bust on a flanking pedestal in a manner similar to the carved prospect door of Walker's desk (Fig. 4). These elements are also found in Langley's Gothic Architecture, Improved by Rules and Proportions (1747) and his second edition of The City and Country Builder's and Workman's Treasury of Designs (1745).

|  |  | ||

| Fig. 3; left: Batty Langley, "Eighth frontispiece for Door," Ancient Architecture Restored, and Improved (London, 1742), plate XXIV. Fig. 4; center: Batty Langley, The Builder's Director or, Bench-Mate (London, 1746), plate 182. Fig. 5; right: Batty Langley, "An Ionick Door for a Room of State," A Sure Guide to Builders (London, 1729), plate 53. | ||||

The profile that Walker carved for the bust is of a Roman statesman. Such symbolism was also selected in the mid-1740s for the two first-floor passage doorways of the State House of the Province of Pennsylvania, today known as Independence Hall. It is possible that Walker, as well as Anthony and Brian Wilkinson, carvers of the doorway plaques, had referred to Langley's 1729 publication, A Sure Guide to Builders, in which an engraving depicted a classical profile bust over the doorway for a "Room of State" (Fig. 5).8

| |

| Fig. 6: Easy chair, attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1745–1755. Mahogany. H. 46-1/2, W. 30-1/2, D. 30-1/8 in. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. W-152. Belonged to Mary Ball Washington. |

Janice Schimmelman's insightful study Archiectural Books in Early America (1999) documents the widespread availability of Langley's works in the colonies long before 1750.9 How early Langley's designs actually appear in Virginia remains open to conjecture, but their employment in the 1740s has been well documented.10 Although none of the Walkers' personal design books are recorded, compelling evidence to consider Langley's impact on the Walker brothers also lies in the author's popularity within the Walkers' clientele, including the Washington, Mason, Mercer, and Fairfax families. Young George Washington acquired one of Langley's publications shortly after commencing renovations at Mount Vernon in the mid-1750s.11 Washington's extended family may have been among Robert Walker's best customers. His mother, Mary Ball Washington (1708–1789), owned an easy chair having four cabriole legs with ball and claw feet made in Walker's shop (Fig. 6), and his half-brother, Augustine Washington (1720–1762), was the likely owner of a side chair and an armchair (Fig. 7) with dogs' head arm terminals and paw feet.12

More importantly, John Mercer of Stafford County, who in 1748 hired William Walker to undertake the construction of his estate, Marlborough, and in 1749 commissioned Robert Walker to make twelve side chairs with gadrooned skirts and two arm chairs with dogs' head carving, owned two works by Langley.13 Mercer's influence on Walker's circle of clientele cannot be overestimated. Mercer served as adviser and attorney to Lawrence Washington, and three of his sons held commissions under George Washington during the French and Indian War. Married to the widow Catherine Mason, he became legal guardian to his wife's nephew, the young George Mason, who frequently visited Mercer's extensive library. One of the largest in the colony, it included copies of Palladio's I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura, Salmon's Palladio Londinensis and, most importantly, Batty Langley's Treasury of Designs (1740) — the latter acquired in 1747.14

| |

| Fig. 7: Armchair, attributed to Robert Walker, King George Country, Virginia, 1750–1755. Mahogany, primary; beech and white oak secondary. H. 39-3/4, Seat: 22-1/2 x 16 in. Splat and crest are nineteenth-century restorations. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. W-4014. This chair, and a set made for William Mercer in 1749, features a gadrooned skirt like the desk in figure 1. |

Langley's Treasury was among the most extensively illustrated design books of the era and contained illustrations of the five orders of architecture, designs for doors, niches, Venetian windows and chimney pieces, and engravings of bookcases, tabernacle frames, chests of drawers, and a plethora of tables and table frames. Not surprisingly, many of Langley's furniture designs have elaborate cabriole legs, often with mask-carved knees and hairy paw feet.15 If Robert Walker had learned how to execute such designs from his early life and career in Scotland, Langley's published works served to legitimize the baroque mode of decoration to Walker's colonial clientele.

If virtually all of the desk's details appear in British design books available to the brothers' clientele during the 1740s, it is equally relevant when deciphering the desk's history to explore the Walkers' relationship with their Virginia patrons during that decade. Here, Thomas Lee of Westmoreland County is of particular note as the possible patron, for it is believed that William Walker helped to construct Stratford in the late 1730s. Shortly thereafter, his brother, Robert, made a remarkable tea table with a highly-carved top, claw feet, and acanthus draped legs (Fig. 8); this table descended in the Lee family.16 Lee was undoubtedly pleased by the quality of the Walkers' work as he subsequently recommended William Walker to rebuild the Capitol building in Williamsburg after the disastrous 1747 fire in which it was all but destroyed.

In 1749, Thomas Lee was appointed acting Governor of the Colony of Virginia, and spent his time intermittently between his Westmoreland "Country" estate and Stratford. Of all the planters of the colony, none could boast stronger patronage of the Walkers, and none other was invested with the Royal authority that is so strongly symbolized by this desk. At Stratford, the visiting Council members would have clearly understood the meaning of the lions' heads and paw feet, and those who were familiar with Batty Langley's works likely recognized the classical bust of the prospect door as employed by Walker as befitting a "Room of State."

|  | |

| Fig. 8; left: Tilt-top table, attributed to Robert Walker, King George County, Virginia, 1740–1750. Mahogany. H. 28-1/4, D. 32-1/2 in. Courtesy of Stratford Hall, Robert E. Lee Memorial Association; photograph by Gavin Ashworth. 1959.1. Fig. 8a, right: Detail of the carving on figure 8. | ||

William Walker and Thomas Lee both died in 1750. Undeterred, Robert Walker continued his business, expressing the new rococo aesthetic with increasing clarity. Yet Walker soon found that his influence was beginning to wane, his patronage by Virginia's aristocracy was falling by the wayside with rising competition from newcomers such as William Buckland and William Bernard Sears of nearby Fairfax county, James Allan and Thomas Miller of Fredericksburg, and Anthony Hay and Benjamin Bucktrout of Williamsburg. After 1750, there would have been little need for the colony's Royal governors — all but one from England — to travel north from Williamsburg to the banks of the Potomac so that they could acquire carved furniture. After the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765, which coincided with the rise of the "neat and plain" style, aristocratic Virginian's inclinations towards rococo taste rapidly cooled, and within the decade the style was all but passé. Robert Walker soon found his remarkable legacy overshadowed by simpler tastes and the understated furniture produced by his former apprentices, who now headed west across the Piedmont. It is therefore fitting that this desk, a masterpiece of American craftsmanship, sheds new light on Robert Walker's artistic output during the first half of the eighteenth century, when he was the unparalleled master cabinetmaker of colonial Virginia.

The author is grateful to Robert Leath of MESDA, Luke Beckerdite of Chipstone,

Tara Chicirda of Colonial Williamsburg, Gretchen Goodell of Stratford Hall,

Carol Cadou and Christina Keyser of Mt. Vernon, Laura Libert of Alexandria, Virginia, and Ann Steuart of Dickerson, Maryland, for their assistance in preparing this article.

1. A Masonic Master's armchair by Williamsburg cabinetmaker, Benjamin Bucktrout, was rediscovered in 1977. It is one of America's few surviving examples of pre-Revolutionary Masonic seating furniture; it is also the only presently known piece of Williamsburg furniture signed by its maker. Ronald L. Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Southern Furniture 1680–1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (Williamsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997), 192–198.

2. Ibid, 185–189.

3. The author is grateful to Robert Leath, for his groundbreaking research on the Walker brothers and the impact it has had on revising understanding of the baroque style in early Virginia. See Leath, "Robert and William Walker and the 'Ne Plus Ultra': Scottish Design and Colonial Virginia Furniture, 1730–1775," in Luke Beckerdite, ed., American Furniture (Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Chipstone Foundation, 2006), 54–95.

4. John Gloag, "Types of Feet," A Short Dictionary of Furniture (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1977), 336; Brock Jobe, Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1993), 236, fig. 52c.

5. Edward Lennox-Boyd, editor, Masterpieces of English Furniture: The Gerstenfeld Collection (London: Christie, Manson and Woods, Ltd., 1998), 104, image 79, no. 43. This aesthetic also exists in a set of hairy paw chairs made circa 1735 for the 1st Earl Poulett of Hinton St. George, Somerset. The Poulett Suite is of particular interest, for it has other features that also relate to Walker's chairs, including cabriole legs in front and rear, and scrolled knees. Similarly, an anonymous, circa 1735, hairy-paw chair with eagle-head arms, brings to mind Robert Walker's now-lost armchair for the Fitzhugh family, as well as the 1745–1755 Mary Ball Washington easy chair by Walker (fig. 6). Leath, 80, fig. 59.

6. Leath, 59, fig. 4. The Duchess of Buccleuch's eldest grandson, Francis Scott, 2nd Duke of Buccleuch (1694/95–1751), served as Right Worshipful Grand Master of the British Freemasons from 1723 to 1724. To the Masons, the lion was seen as an emissary of the sun, which in turn symbolized the Masonic virtues of light, truth, and regeneration. The throne of King Solomon contained carved lions and eagles on each approaching step, and from the earliest years, Masonic ritual incorporated references to the "strong grip of the lion's paw" — the five points of Masonic fellowship corresponding to each of the five talons. Where this iconography fits into the larger chain of Scotland's stylistic consciousness, and whether it had an impact on artisans in the Buccleuch circle, is open to tantalizing conjecture.

7. Leath, 55–65.

8. It is significant to note that such profile busts, which had been popular through the Renaissance, soon thereafter lost much of their cache; indeed, by the time Thomas Chippendale published the Director in 1754, he forsook profiles altogether, preferring, instead, fashionable frontal and three-quarter busts. After 1750, the unadorned classical profile selected by Robert Walker for the desk would have been passé within fashionable circles.

9. Leath, 61–63, 66–67, 71, 73–76.

10. Architectural historian Thomas Waterman made a worthy observation concerning Robert "King" Carter's 1732–1735 Christ Church, Lancaster County, Virginia—periodically conjectured to have been built by William Walker: "A curious feature of the west front is the oval window over the doorway. This is not an entirely successful element, but it has a certain quaintness. No such design occurs in [William Salmon's] Palladio Londinensis, but there are numerous examples in other design books such as Gibb's and Langley's publications." Waterman also noted that Williamsburg architect Richard Taliaferro, working principally before 1750, relied extensively upon Langley, particularly The Builder's Jewel, or, The Youth's Instructor and Workman's Remembrancer (London, 1741). See Thomas Waterman, Mansions of Virginia, 1706–1776 (New York, NY: Bonanza Books, 1945), 125–126, 4405–4406. Waterman also cites Leoni's Designs for Buildings, William Salmon's Palladio Londinensis, and Gibb's Book of Architecture I, as influential.

11. Washington purchased Langley's New Principles of Gardening (1728), as quoted in Robert F. Dalzell, Jr. and Lee Baldwin Dalzell, George Washington's Mount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 58.

12. The easy chair was not listed in Mary Ball Washington's husband's probate inventory, so she must have acquired it after 1743. During Mary's long years as a widow, her easy chair would have resided at Ferry Farm Plantation on the north side of the Rappahannock River, nearly opposite Fredericksburg. It is probably the "1 Easy Chair" included in the written memorandum of Mrs. Washington's effects not specifically bequeathed in her will. Augustine Washington, who lived at Wakefield Plantation in Westmoreland County, was the likely owner of the side chair and armchair. The armchair, which exists in fragmentary form (the crest rail and splat were replaced in the nineteenth century) is important in being one of two objects with paw feet attributed to Walker's shop. Given the similarities in the side chair's and armchair's knee carving and comparable use of applied molding, it is tempting to speculate that the chairs are from two sets commissioned by the same patron. If so, they might represent the "1 dozn. Walnut Chairs" and "1 Dozn. Mahogany Chairs & 2 Arm Do." listed in Augustine Washington's 1764 probate inventory. Leath, 80–82, figs. 39–43.

13. Leath, 68–70, figs. 18–24.

14. Dalzell, 172; C. Malcolm Watkins, The Cultural History of Marlborough, Virginia (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1968), 37–39, 205. At least six editions of Langley's Treasury (1740) are known to have been in use in Virginia; see Charles E. Brownell, et al, The Making of Virginia Architecture (Richmond, VA: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1992), 42.

15. Robert Walker built at least one cabinet on stand with cabriole legs. Formerly attributed to Peter Scott, the walnut cabinet has a provenance that ties it to King William County, Virginia. Hurst and Prown, 409–412, no.126.

16. The carving executed on this tea table is notable for the tiny, comma-like ornament just below the tip of the acanthus-carved knee, tilted discreetly to one side. For all of its subtlety, this detail signaled a shift away from baroque symmetry and toward the new stylistic consciousness of the rococo. On later furniture, even when Robert Walker relied on familiar details he first used in the 1740s —such as dogs' heads-arm terminals — these early features were always accompanied by a more current decorative vocabulary, such as rococo knee carving or straight, rather than cabriole, legs.

Sumpter Priddy lives in Alexandria, Virginia, where he resides over his gallery, researches the material culture of the early South, and consults for collectors and museums.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2009 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|