Dove / O’Keeffe: Circles of Influence

|

by Sarah Hammond & Teresa O’Toole

|

Title Images: Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946). A Portrait, 1918. 9-11⁄16 x 7¾ inches. |

eorgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) is most famous for her sinuous depictions of flowers and the American southwest, yet she credited abstractionist Arthur Dove (1880–1946) as the individual who had the most significant impact on her development as a young artist. As she later reflected, “[T]he way you see nature depends on whatever has influenced your way of seeing…I think it was Arthur Dove who affected my start, who helped me to find something of my own.”1

When O’Keeffe arrived on the New York art scene in the mid-1910s, Dove was already a leading figure of the American modernist movement, recognized by the renowned photographer and critic Alfred Stieglitz for his innovative use of sensual, abstract forms to evoke the flowing rhythms and patterns of nature. Stieglitz featured both artists at his celebrated 291 gallery before he became romantically involved with O’Keeffe in 1918. O’Keeffe credited Dove’s pastels as her first introduction to American modernism. Dove, in turn, was impressed by her bold interpretations of nature and looked to her watercolors as a source of renewal for his own artistic practice into the 1930s.

By the 1920s, critics repeatedly paired Dove and O’Keeffe, reading their work through a Freudian lens and casting them as the quintessential male and female practitioners of modernist art in America. Beyond these gendered readings of their work, a deeper aesthetic and philosophical affinity connected the two artists. Their oils, pastels, and watercolors often focused on similar themes of nature, transience, and light. Even after their styles and interests began to diverge around 1930 and O’Keeffe began spending more time in the American southwest, Dove and O’Keeffe remained committed to each other’s work.

|

Arthur Dove (1880–1946), Movement No. I, ca. 1911. Pastel on canvas, 21⅜ x 18 inches. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio; gift of Ferdinand Howald. Courtesy of and © The Estate of Arthur Dove/Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

After seeing a reproduction of one of Dove’s pastels in Arthur Jerome Eddy’s book Cubists and Post-Impressionism (1914), O’Keeffe took to the streets of New York looking for more of Dove’s work. This search ultimately brought her to the Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters (1916), where she saw a number of Dove’s pastels, including this work, in which he explores the fleeting and luminous qualities of nature through the abstraction of organic forms into dynamic geometric shapes. In an interview with the Chicago Examiner about his abstractions, Dove explained, “Yes, I could paint a cyclone. Not in the usual mode of sweeps of gray wind over the earth, trees bending and a furious sky above. I would paint the mighty folds of the wind in comprehensive colors; I would show repetitions and convolutions of the range of the tempest.”2 These early pastels by Dove had a lasting impact on O’Keeffe, challenging what she had learned through her studies at the Art Students League of New York and influencing the course of her work.

|

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Blue I, 1916. Watercolor on paper, 30⅞ x 22¼ inches. Private collection. © 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In April 1917, Alfred Stieglitz featured an installation of Georgia O’Keeffe’s drawings and watercolors, including Blue I, in the final exhibition at 291. The dramatic exploration of nature in these works reveals loose visual and thematic connections with Dove’s art, foreshadowing their ultimate pairing by the critics in the 1920s and 1930s. After seeing O’Keeffe’s watercolors at 291, Dove wrote to Stieglitz, “This girl…is doing what we fellows are trying to do. I’d rather have one of her watercolors than anything I know.”3 Dove took up the medium of watercolor in the 1930s as a way of reinvigorating his work, looking back to what he called O’Keeffe’s “burning watercolors” of the 1910s for her use of color and light to capture the natural landscape. Dove used the medium industriously, producing one or two a day until his death in 1946.

|

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), New York with Moon, 1925. Oil on canvas, 48 x 30¼ inches. © Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on loan at the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the mid-1920s, O’Keeffe began working on a series of New York cityscapes, fixating on the towering skyscrapers that dominated the city. In this work, the built environment is reduced to geometric yet still readable forms cast in bold areas of light and shadow, suggesting that O’Keeffe — always sensitive to color and tone — based her representation on real observation and experience. Instead of focusing on the grime and din of the crowded city, which she detested, O’Keeffe chose to paint the effects of various light sources upon its buildings, endowing the urban landscape with a sense of meditative calm and silence. While this depiction of New York is more representational than abstract, there are elements of the work that echo O’Keeffe’s more radical interpretations of nature. The treatment of the sky, with its layers of clouds and partially obstructed moon, is evocative of her other night scenes, like those she painted at Lake George. Similarly, the concentric circles of the luminous streetlight return as an aesthetic element in later works by both Dove and O’Keeffe. Her New York pictures would meet with harsh criticism; male critics considered O’Keeffe’s architectural forms inappropriate subjects for a woman artist, and even Stieglitz left this painting out of his 1925 exhibition Seven Americans.

|

Arthur Dove (1880–1946), River Bottom, Silver, Ochre, Carmine, Green, 1923. Oil on canvas, 24 x 18 inches. Collection of Michael and Fiona Scharf. Courtesy of and © The Estate of Arthur Dove/Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

Many of Dove’s abstractions focus on capturing the transient and elusive qualities of nature. Describing his approach to abstraction, Dove explained, “Why not make things look like nature? Because I do not consider that important and it is my nature to make them this way. To me it is perfectly natural. They exist in themselves, as an object does in nature.”4 In this work, Dove captures the play of light created by the river’s running water by using amorphous shapes and dynamic colors. O’Keeffe recognized Dove’s affinity for abstraction saying, “I think Dove came to abstraction quite naturally…It was his way of thinking…Dove had an earthy, simple quality that led directly to abstraction.”5

|

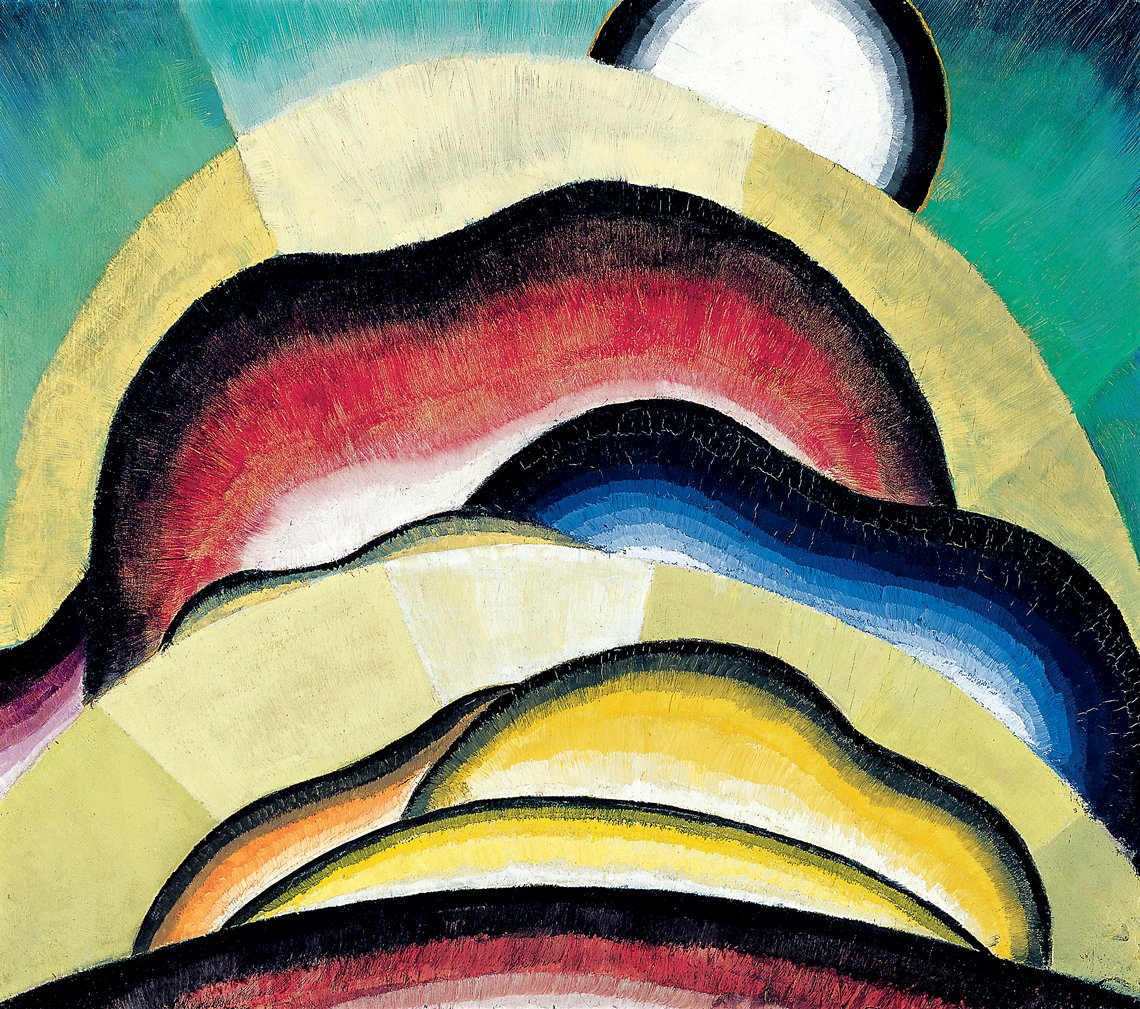

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), From the Lake, No. 1, 1924. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches. Nathan Emory Coffin Collection of the Des Moines Art Center, Iowa. Purchased with funds from the Coffin Fine Arts Trust. Photography by Michael Tropea, Chicago. © 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In From the Lake, O’Keeffe explores the fleeting effects of light on the surface of water through the use of striking bands of color. From 1918 to 1929, when she started to split her time between New York and New Mexico, O’Keeffe spent much of the summer and fall at Stieglitz’s family estate in Lake George, New York. The effect that Lake George had on O’Keeffe is apparent in many of her works, which depict the natural landscape of the region and its surrounding mountains and wildlife. Not only did the lake provide artistic inspiration through its innate beauty, but it also provided a chance for O’Keeffe to mix with Stieglitz’s other guests, who often included leading artists and critics from New York’s modernist scene.

|

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI, 1930. Oil on canvas, 36 x 18 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Alfred Stieglitz Collection; bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

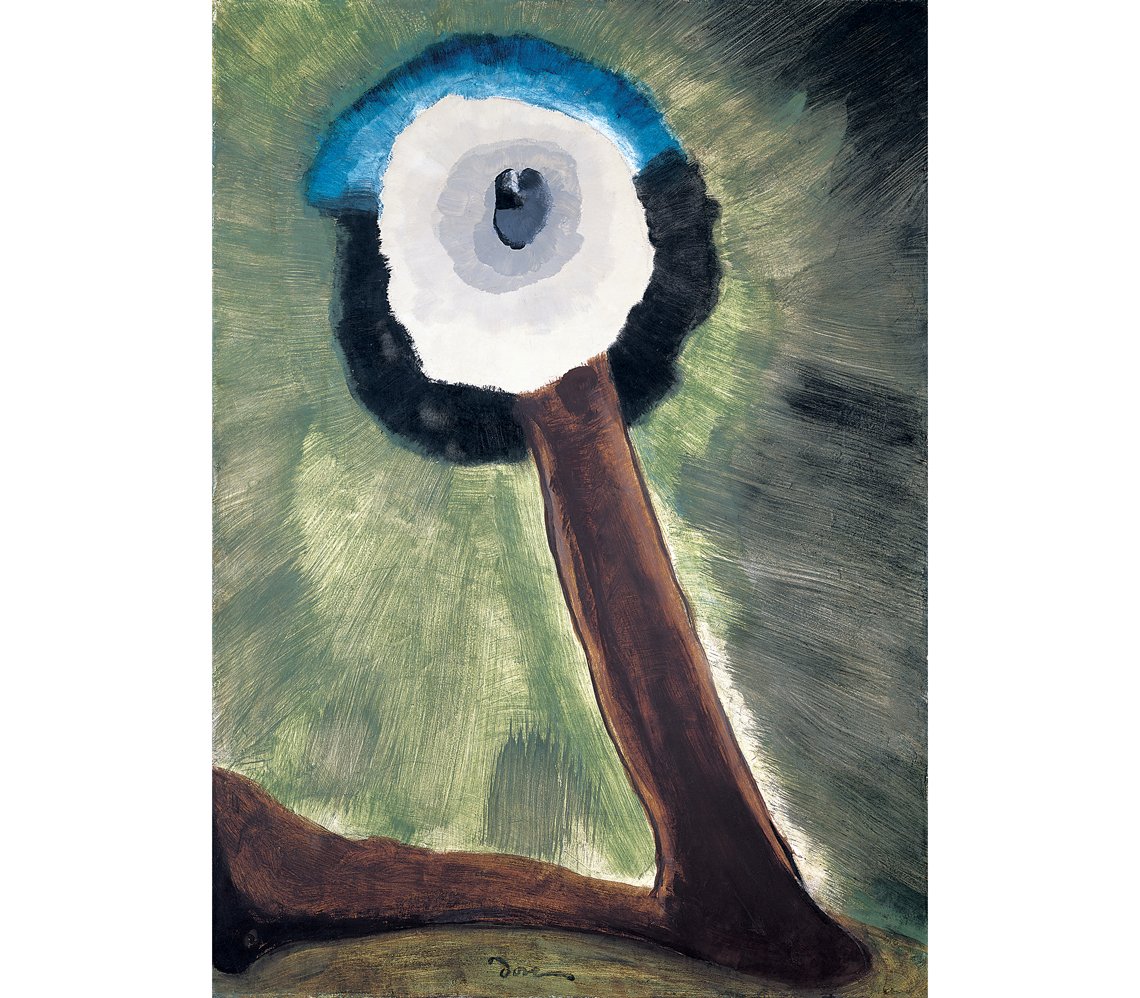

Freudian philosophies of gender and psychoanalysis began to infiltrate American art criticism by the 1920s and 1930s, quickly becoming a basis for the critical pairing of Dove and O’Keeffe’s work. As one critic asserted, “Dove is very directly the man in painting, precisely as Georgia O’Keeffe is the female; neither type has been known in quite the degree of purity before.”6 In works such as O’Keeffe’s Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI and Dove’s Moon (below), the aesthetic connection between the two is evident through their overtly phallic abstractions of natural forms. Neither artist tries to hide the blatant allusion to male genitalia in each of these works, further fueling the fire of critics who were already quick to assign sexual meaning to Dove and O’Keeffe’s work.

|

Arthur Dove (1880–1946), Moon, 1935. Oil on canvas, 35 x 25 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Photography by Lyle Peterzell. Courtesy of and © The Estate of Arthur Dove / Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

The overtly sexual interpretations of O’Keeffe’s work remained a source of discomfort for the artist throughout her lifetime. As she explained, “[I]t embarrassed me…They make me seem like some strange unearthly sort of a creature floating in the air — breathing in clouds for nourishment — when the truth is that I like beef steak — and like it rare at that.”7 Dove, on the other hand, recognized that the critical attention linking his work with O’Keeffe’s helped him to reemerge in the American art scene after a period of relative inactivity in the late 1910s and early 1920s. In a letter to Stieglitz, Dove declared, “[T]he bursting of a phallic symbol into white light may be the thing we all need.”8 The representation of the moon in this painting also signifies a common element in Dove and O’Keeffe’s work: both artists were interested in depicting the fleeting effects of the moon and the sun.

|

Arthur Dove (1880–1946), Sunrise, 1924. Oil on panel, 18¼ x 20⅞ inches. Milwaukee Art Museum; gift of Mrs. Edward R. Wehr. Photography by John R. Glembin. Courtesy of and © The Estate of Arthur Dove / Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

Before his personal and professional connections with Stieglitz and O’Keeffe revitalized his painting career, Dove was very much a man of the soil. Though he did freelance illustrations for weekly publications like Harper’s, his primary livelihood until the 1920s was working as a farmer in Connecticut, with his wife and son, where he grew crops and kept chickens. This familiarity with nature and the inexorable rhythm of the seasons, ultimately guided Dove’s abstractions on canvas and on paper, and his oeuvre testifies to his emotional connection with the sun, wind, and rain. Luminous paintings such as Sunrise speak to the artist’s ambition to depict what he called the “condition of light” that permeated the natural world. This inner radiance, he wrote, “applied to all objects in nature, flowers, trees, people, apples, cows. These all have their certain condition of light, which establishes them to the eye, to each other, and to the understanding.”9 O’Keeffe, in later musings on her close artistic kinship with Dove, would declare, “Dove is the only American painter who is of the earth.”10

|

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Sunrise, 1916. Watercolor on paper, 8⅞ x 11⅞ inches. Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth. © 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

O’Keeffe turned to watercolor around the time she first saw Dove’s pastels in person at the Forum Exhibition in 1916; his sweeping, exuberant forms and radiant colors inspired her to experiment with a richer palette in her own work. In a 1916 letter to her friend Anita Pollitzer, O’Keeffe wrote of her desire to get outdoors and have “watercolor evenings,” explaining that the vibrant hues of the sun’s radiant display posed a wonderful challenge to any artist trying to replicate their fleeting beauty.11 O’Keeffe’s watercolors were among the earliest works to which critics applied gendered readings and interpretations, wherein they translated the “delicacy” of her work into a kind of feminine mystique. Henry Tyrell of the Christian Science Monitor lauded O’Keeffe for her “sensitized line,” in which she “found expression in delicately veiled symbolicalism for what every woman knows, but what women heretofore have kept to themselves.”12

|

Arthur Dove (1880–1946), Fog Horns, 1929. Oil on canvas, 18 x 26 inches. Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Anonymous gift (FA 1954.1). Courtesy of and © The Estate of Arthur Dove / Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

In his statement in the Forum Exhibition catalogue, Dove identified “the reality of the sensation” as the driving force behind his art. For Dove, the immediacy of the physical world, mediated by the artist’s sensory perception, directed the expression of his “inner consciousness” through color and form. Seeking out the “essence” of this “reality” was a “delightful adventure” for Dove, the pursuit of which allowed him to “enjoy life out loud.”13 Critics saw this robustness and bravado as distinctly American sensibilities. In Fog Horns, Dove gave visual form to the booming warning knolls that he must have heard from the deck of his yawl, the Mona, on Long Island Sound. Amorphous circles hovering in an undefined space suggest waves of sound emanating from the blaring horns, penetrating through the dismal grays of heavy mist. O’Keeffe was also interested in conveying the experience of sound and music through painting, as she explained in a letter to Anna Pollitzer, “I like [music] better than anything in the world — Color gives me the same thrill once in a long long time…it is usually just the outdoors or the flowers or something that will call a picture to my mind — will affect me like music.”14

|

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), The Lawrence Tree, 1929. Oil on canvas, 31⅛ x 39¼ inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn. The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund. © 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Painted during O’Keeffe’s first extended trip to New Mexico, The Lawrence Tree was named for the writer D. H. Lawrence, on whose ranch the enormous ponderosa pine grew. It was after she started spending time in the southwest that O’Keeffe’s practice shifted from the boldly abstract works she had made in New York to the largely representational depictions of sand, skulls, and flowers for which she is best known today. The influence and experience of Arthur Dove’s work was never far, however; in a 1962 interview she commented, “My house in Abiquiu is pretty empty; only what I need is in it. I like walls empty. I’ve only left up two Arthur Doves, some African sculpture, and a little of my own stuff.”15 O’Keeffe’s abiding respect for Dove and his philosophical take on abstraction can be sensed even in works such as The Lawrence Tree—the dizzying angle of the upward thrust of the tree trunk and the brilliance of the blue sky give the work a sense of immediacy, as though the viewer were also sitting beneath the tree, gazing up to the starry sky.

|

Arthur Dove (1880–1946), Willow Tree, 1937. Oil on canvas, 20 x 28 inches. Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Fla; bequest of R. H. Norton. Courtesy of and © The Estate of Arthur Dove/ Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.

While O’Keeffe’s work after 1930 tended toward naturalism, many of Dove’s later paintings continued to reduce natural forms into ever-more radical abstractions. Here, the flat, nonrepresentational spiral that dominates the picture field seems to bear little resemblance to the tree that had ostensibly inspired it, yet it still suggests the graceful bow of willow branches. This reduction of subjects to a harmonious interplay of shapes and colors speaks to Dove’s lasting adherence to the principles that had guided his earliest creations. He continued to seek out the “essence” of objects and experience alike — or, as he had written for the Forum Exhibition catalogue, “to give back in my means of expression all that it gives to me: to give in form and color the reaction that plastic objects and sensations of light from within and without have reflected from my inner consciousness.”16

1. Georgia O’Keeffe, quoted in Katharine Kuh, “Georgia O’Keeffe,” The Artist’s Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), 189.

2. Arthur Dove, quoted in H. Effa Webster, “Artist Dove Paints Rhythms of Color,” Chicago Examiner (15 Mar. 1912): 12.

3. Alfred Stieglitz to Sheldon Cheney, 24 Aug. 1923, Cheney Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., reel 3947, frames 449–50.

4. Arthur G. Dove, “An Idea,” in Arthur G. Dove Paintings, 1927 (New York: The Intimate Gallery, 1927), n.p.

5. Georgia O’Keeffe, quoted in Calvin Tomkins, “The Rose in the Eye Looked Pretty Fine,” The New Yorker (30 Mar. 1974): 62.

6. Paul Rosenfeld, “Arthur G. Dove,” in Port of New York: Essays on Fourteen American Moderns (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1924), 170.

7. Georgia O’Keeffe to Mitchell Kennerley, fall 1922, in Georgia O’Keeffe: Arts and Letters (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art; Boston: New York Graphic Society Books, 1987), 170–71.

8. Arthur Dove to Alfred Stieglitz, 4 Dec. 1930, in Dear Stieglitz, Dear Dove, ed. Ann Lee Morgan (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1988), 202.

9. Arthur Dove, quoted in Samuel M. Kootz, Modern American Painters (New York: Brewer & Warren, 1930), 37.

10. Georgia O’Keeffe, quoted in Suzanne Mullett, “Arthur G. Dove (1880– ), A Study in Contemporary Art” (M.A. thesis, The American University, Washington, D.C., 1944), 27.

11. Georgia O’Keeffe to Anita Pollitzer, Feb. 1916, in Lovingly, Georgia: The Complete Correspondence of Georgia O’Keeffe and Anita Pollitzer, ed. Clive Giboire, introduction by Benita Eisler (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 131.

12. Henry Tyrrell, “New York Art Exhibition and Gallery Notes: Esoteric Art at ‘291,’” The Christian Science Monitor (4 May 1917): 10, reprinted in Barbara Buhler Lynes, O’Keeffe, Stieglitz and the Critics, 1916–1929 (Ann Arbor, Mich.: UMI Research Press, 1989), 168.

13. Arthur G. Dove, “Statement,” in The Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters: March 13th to March 25th, 1916 (New York: Anderson Galleries, 1916), n.p.

14. Georgia O’Keeffe to Anita Pollitzer, 25 Aug. 1915, in Georgia O’Keeffe, Art and Letters, 143.

15. Georgia O’Keeffe, quoted in Katharine Kuh, The Artist’s Voice, 190.

16. Dove, “Statement,” in The Forum Exhibition of Modern American Painters, n.p.

Sarah Hammond (curatorial assistant) and Teresa O’Toole (publications and curatorial intern) of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute worked with curator Debra Balken on Dove/O’Keeffe: Circles of Influence.

This article was originally published in the Early Summer 2009 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|